有多少移民抵达马萨诸塞州? 很难确定,但他们不断出现

【中美创新时报2024年4月1日编译讯】(记者温友平编译)近连续两年,越来越多的移民——许多人怀孕了或带着孩子——来到马萨诸塞州,逃离暴力和贫困,寻找住房、食物和安全。人潮的涌入给州政府官员带来了压力,他们纷纷支持紧急援助庇护所计划,他们估计该计划在下一财年将花费高达 9.15 亿美元。当政府计算出如何支付费用时,有一个关键数字官员们并不确定:实际有多少移民抵达。《波士顿环球报》记者萨曼莎·格罗斯(Samantha J. Gross)对此进行了下述详细报道。

州长莫拉·希利 (Maura Healey) 的政府从马萨诸塞州的重新安置机构获取数据,这些机构是一个组织网络,帮助新移民满足基本需求,并向州报告那些有资格获得联邦服务的人。通过这一过程,从 2022 年 10 月到联邦财政年度 2023 年 9 月,政府已登记了超过 11,000 名移民。

这比上一财年增加了 152% 以上,当时该州从各机构收到了 4,359 名移民的报告。但卫生与公众服务部发言人奥利维亚·詹姆斯表示,这仍然“不是全面统计”涌入该州的新移民总数。

她说,该州只能统计在马萨诸塞州接受联邦服务的新移民。该群体包括在美国居住了很长一段时间的重新安置难民,以及拜登政府认为在逃离生命威胁或其他紧急情况后有资格获得医疗补助和现金援助等福利的一些海地和古巴移民。据该国称,国家数据中72%的移民来自海地,13%来自乌克兰,5%来自阿富汗或叙利亚,10%来自其他国家的难民。

该州的统计数据不包括不符合某些类别的法律身份,因此没有资格获得联邦服务的移民,例如旅游签证逾期居留或非法进入美国的人。然而,处于该州移民危机前线的非营利组织工作人员表示,这些人经常出现在食品分发处、日间庇护所和其他致力于帮助新移民找到立足点的项目中。

切尔西非营利组织 La Colaborativa 的执行董事格拉迪斯·维加 (Gladys Vega) 表示:“并非每个没有证件来到这里的人都会通过安置机构。”La Colaborativa 不是安置机构,但每年为数百名新移民提供捐赠食品、语言课程和服务。免费法律援助。

该州统计数字的差距引发了人们的疑问:政策制定者和非营利组织是否拥有充分了解和规划需求范围所需的数据。它还揭示了移民潮在短短一年内激增了多少,在距离美墨边境数千英里的地方造成了一场危机。

每一天,马塔潘移民家庭服务研究所的候诊室都挤满了海地移民,里面装饰着由世界各地的微型旗帜组成的花环。在外面,家庭等待与工作人员会面,工作人员将为他们联系住房和捐赠的物品,如婴儿车、冬季夹克和背包。

那里的领导人表示,该非营利组织在 2023 财年已接待了超过 9,400 名新抵达的移民。其中绝大多数是海地人。

切尔西一家非营利组织的负责人(该组织同时也是数百人的日间庇护所)表示,她的组织已帮助今年抵达马萨诸塞州的 1000 多名拉丁美洲移民。

马萨诸塞州非营利性安置机构——总部位于波士顿的新英格兰国际研究所的内部数据显示,该组织在 2023 财年帮助了来自 49 个国家的 10,047 人,其中可能包括一些由其他机构服务的移民。

La Colaborativa 的 Vega 表示,过去两年过得很艰难,因为新来者的步伐不断加快。 几周内,会有 30 名新人到 La Colaborativa 寻求帮助; 其他周则接近 70 个。

2022 年,时任州长查理·贝克 (Charlie Baker) 政府报告称,该州在 2022 财年为 4,000 名移民提供了服务。但这一数字不包括由非安置机构的其他类型非营利组织(例如信仰团体或当地食品储藏室)提供服务的数千名移民。

新英格兰国际学院院长杰夫·蒂尔曼 (Jeff Thielman) 表示,在他的机构预约注册服务的等候名单现已延长至 5 月,这意味着有数百名可能符合条件的新移民尚未被添加到该州数据库的服务名单中。

蒂尔曼说,这意味着州官员向联邦政府报告的人数减少了,这可能会影响流向他这样的机构的资金数额。

几个月来,希利和其他州领导人一直在努力应对海地、中美洲和南美洲及其他地区逃离动乱和贫困的移民涌入问题。他们经常需要医疗援助并帮助应对复杂的移民系统。再加上住房危机,许多新移民几乎不可能找到负担得起的住所。

八月,希利向联邦政府寻求帮助,她宣布了一项紧急声明,旨在解决该州负担过重的庇护系统问题。她曾两次写信给拜登政府,恳求官员迅速向该州收容所系统不堪重负的数千名移民发放工作许可证,并汇款帮助该州提供住房和交通等必要资源。

与此同时,除了其他投资外,该州还向紧急避难系统投入了数亿美元。它向联合之路 (United Way) 提供了 500 万美元的赠款,用于与其他非营利组织合作,为等待进入庇护所系统的家庭开放超额庇护所,向吸收移民进入学生群体的学校返还数千美元,并创建了一个全新的合法庇护所。服务计划帮助移民整理庇护申请,以便他们最终获得工作许可。

该州面临的挑战并非独一无二。

一月份,希利和九位州长一起呼吁联邦官员修复该国的移民制度,并敦促两大政党领导人“共同努力解决人道主义危机”。

即使联邦政府也没有保留移民从边境拘留所释放后去了哪里的完整记录。

当移民抵达美墨边境,从政治或经济动荡的国家寻求庇护时,那些没有立即被拒绝的移民通常会向联邦当局自首,并收到“通知”,要求日后在移民法官面前出庭。

随着这些新移民分散到全国各地,州和地方政府最终承担起照顾他们并跟踪有多少人的负担。

蒂尔曼的员工在过去一年多的时间里一直忙于工作,他表示,联邦政府提供的更多帮助对于满足需求至关重要。 但这需要更准确地了解该州面临的情况。

“来自联邦政府的资金没有足够快地到达居住在英联邦的人们手中,”他说。 “钱不会流向州政府,但[移民]正在寻求更多的州政府援助。这给其他人带来了帮助他们摆脱困境的压力。”

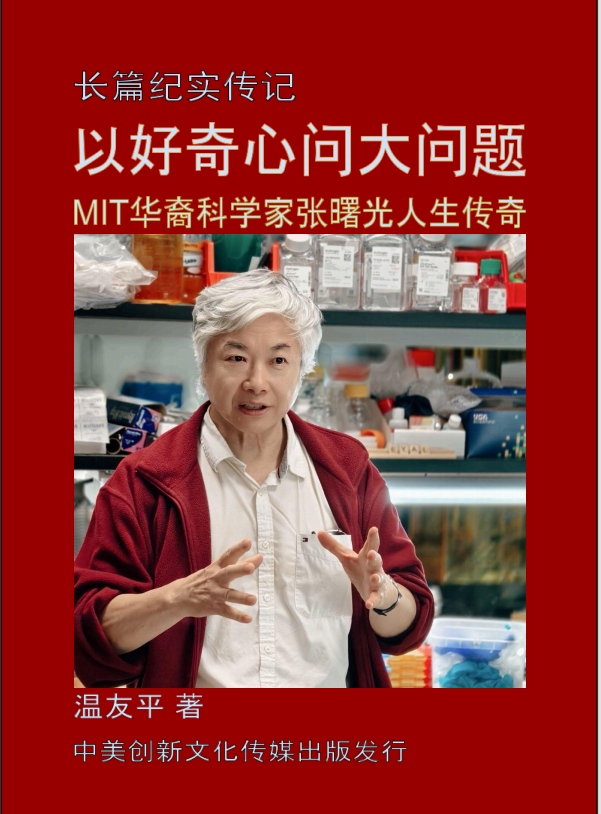

题图:住在剑桥避难所的移民在切尔西的 La Colaborativa 度过了一天。ERIN CLARK/GLOBE STAFF

附原英文报道:

How many migrants have arrived in Massachusetts? It’s hard to know for sure, but they keep coming.

A Globe review indicates a dramatic increase in migrants from the start of the current immigration wave

By Samantha J. Gross Globe Staff,Updated April 1, 2024

For nearly two consecutive years, a rising stream of migrants — many pregnant or with children by their side — have arrived in Massachusetts, fleeing violence and poverty in search of housing, food, and security. The influx has put pressure on state officials who have scrambled to support the emergency assistance shelter program, which they estimate will cost a whopping $915 million in the next fiscal year.

As the state figures out how to cover the cost, there’s a key figure that officials don’t know for sure: how many migrants are actually arriving.

Governor Maura Healey’s administration gets its data from Massachusetts-based resettlement agencies, a network of organizations that help new arrivals with basic needs and report those eligible for federal services to the state. Through that process, the administration has logged more than 11,000 migrants from October 2022 through September 2023, the federal fiscal year.

That represents an increase of more than 152 percent over the previous fiscal year, when the state received reports of 4,359 migrants from the agencies. But it’s still “not a comprehensive count” of the total number of new arrivals pouring into the state, said Olivia James, a spokesperson for the Department of Health and Human Services.

The state, she said, can only count the new arrivals who receive federal services in Massachusetts. That group includes resettled refugees who have lived in the United States for a significant period of time and some Haitian and Cuban migrants whom the Biden administration deemed eligible for benefits such as Medicaid and cash assistance after fleeing life-threatening or other urgent situations. According to the state, 72 percent of migrants counted in state figures were from Haiti, 13 percent were Ukraine, 5 percent were Afghan or Syrian, and 10 percent were refugees from other countries.

The state’s count does not include immigrants who don’t qualify for certain categories of legal status and thus aren’t eligible for federal services, such as people who overstay tourist visas or illegally cross into the United States. Those individuals, however, often show up at food pantries, day shelters, and other programs dedicated to helping new arrivals find their footing, say the nonprofit workers at the front lines of the state’s migrant crisis.

“Not every person who comes here without documents goes through resettlement agencies,” said Gladys Vega, executive director of La Colaborativa, a Chelsea nonprofit that is not a resettlement agency but serves hundreds of new immigrants every year with donated food, language classes, and free legal aid.

The gap in the state’s count raises questions about whether policymakers and nonprofits have the data necessary to fully understand and plan for the scope of the need. It also reveals how much the migrant wave has swelled in just a year, creating a crisis thousands of miles from the US-Mexico border.

On any given day, the waiting room at Immigrant Family Services Institute in Mattapan — decorated with a garland made up of miniature flags from around the world — is packed with Haitian migrants. Outside, families wait for their turn to meet with a staff member who will connect them with housing and donated goods, such as strollers, winter jackets, and backpacks.

Leaders there say the nonprofit has received more than 9,400 newly arrived migrants in fiscal year 2023. The vast majority of them are Haitian.

And the director of a nonprofit in Chelsea, which doubles as a day shelter for hundreds, said her group has helped more than 1,000 Latin American migrants who have reached Massachusetts this year.

Internal figures from one nonprofit Massachusetts resettlement agency, the Boston-based International Institute of New England, show the group helped 10,047 people from 49 countries in fiscal year 2023, which could include some migrants served by other agencies.

The last two years have been difficult, La Colaborativa’s Vega said, as the pace of new arrivals has continued to accelerate. Some weeks there are 30 newcomers who seek help at La Colaborativa; other weeks there are closer to 70.

In 2022, then-governor Charlie Baker’s administration reported the state had served 4,000 migrants in the fiscal year 2022. But that count excluded thousands of migrants served by other types of nonprofits that are not resettlement agencies, such as faith-based groups or local food pantries.

Jeff Thielman, who heads the International Institute of New England, said the waitlist for an appointment at his agency to get enrolled in services now extends to May, meaning there are hundreds of new, potentially eligible arrivals who have yet to be added to the state’s database.

That means fewer people are reported by state officials to the federal government, which could affect how much money is funneled toward agencies like his, Thielman said.

For months, Healey and other state leaders, have been working to manage the influx of migrants fleeing turmoil and poverty in Haiti, Central and South America, and beyond. They often come in need of medical assistance and help navigating the complex immigration system. And coupled with a housing crisis, it’s nearly impossible for many new arrivals to find affordable shelter.

In August, Healey appealed to the federal government for help as she announced an emergency declaration aimed at addressing the state’s overburdened shelter system. She has twice written to the Biden administration, imploring officials to quickly grant work permits to the thousands of migrants who have overwhelmed the state’s shelter system and to send money to help the state provide necessary resources such as housing and transportation.

In the meantime, the state has poured hundreds of millions of dollars into the emergency shelter system, among other investments. It awarded a $5 million grant to the United Way to partner with other nonprofits and open overflow shelters for families awaiting a slot in the shelter system, paid back thousands to schools who have absorbed migrants into their student populations, and created a brand-new legal services program to help migrants put together asylum applications so that they can eventually obtain permits to work.

The challenge the state faces is not unique.

In January, Healey was among nine governors who called on federal officials to fix the country’s immigration system, urging leaders from both major political parties “to work together to solve what has become a humanitarian crisis.”

Even the federal government does not keep complete records of where migrants go after they are released from custody at the border.

When migrants arrive at the US-Mexico border seeking asylum from countries rife with political or economic unrest, those not immediately turned away often turn themselves in to federal authorities and receive a “notice to appear” in front of an immigration judge at a future date.

As these new arrivals disperse across the country, state and local governments end up with the burden of caring for them — and keeping track of how many are there.

Thielman, whose staff has been crushed with work for the last year-plus, said more help from the federal government is crucial to keep up with the need. But that will require a more accurate picture of what the state is facing.

“Money from the federal government is not coming to people living in the Commonwealth fast enough,” he said. “The money isn’t coming to the state, but [migrants] are looking out for more state assistance. That puts the pressure on everyone else to help them out.”