马萨诸塞州居民是美国最大的彩票玩家 但财富分配并不公平

【中美创新时报2025 年 1 月 18 日编译讯】(记者温友平编译)多年来,马萨诸塞州彩票一直受到批评,称其掠夺低收入人群,向他们提供只有极少数人才能实现的即刻致富前景。《波士顿环球报》记者Esmy Jimenez 对此作了下述报道。

但马萨诸塞州在发放从彩票销售中收集的数亿美元时也存在同样严重的不公平现象:低收入社区获得的州政府援助远低于其居民在彩票上的支出,这与彩票最初的想法相反,即较贫穷的城镇将受益最多。

而且,多次试图修复 Beacon Hill 的系统都徒劳无功。

例如,在切尔西,一个以拉丁裔为主的城市,家庭收入中位数约为 72,000 美元,供应商在 2023 年售出了超过 5000 万美元的彩票,但该市仅获得了约 950 万美元,约占其销售额的 18%。而在布罗克顿,一个以黑人为主、家庭收入相似的城市,居民在彩票上花费了超过 1.2 亿美元,在该州排名第五。该市获得了约 2400 万美元。

与此同时,伍斯特县的乡村小镇哈佛,家庭收入中位数为 20 万美元,获得了近 200 万美元的援助,但去年却没有售出一张彩票。

这种脱节归因于 50 多年前首次设想的当地彩票援助公式从未进行调整以保护较贫穷的社区,当它们的拨款不足时。

马萨诸塞州的彩票资金分配方式独一无二,大部分资金不受限制,而不是专门用于教育或基础设施等特定用途。例如,佐治亚州去年将 15 亿美元的彩票收益用于教育计划,例如为州立学院和大学的学生提供奖学金、为 4 岁儿童提供免费学前教育以及为当地学校升级技术。

在这里,虽然彩票销售收入的大部分用于支付中奖者,但每销售一美元,约有 19 美分将用于州的普通基金,然后作为对城市和城镇的援助。支出最初基于人口数量和财产价值,旨在帮助低收入城市弥补收入不足或额外需求。大衰退之后,立法者转向将彩票援助和额外援助合并为一个资金池的系统,情况发生了变化。然后,城市和城镇将根据州收入获得一定比例的资金。

“显然,随着时间的推移……那些本来就获得较少援助的社区会越来越落后,”新贝德福德的众议员安东尼奥·卡布拉尔 (Antonio Cabral) 表示,他多年来一直提出法案,要求改变该州大量过时的援助方案。据马萨诸塞州市政协会的一份报告称,门户城市和农村社区尤其难以为当地服务提供资金,需要更多的一般援助。

我们需要“看看所有现行的方案,然后说,‘好吧,上次修订或改革是什么时候?’”卡布拉尔说。“自 1972 年该州首次发行彩票以来,世界已经发生了变化。”

如今,彩票已经根深蒂固,居民可以在修车、在自助洗衣店洗衣服或购买杂货时购买刮刮彩票。马萨诸塞州的人均彩票支出是全国最高的,约为每名居民 839 美元。上个财年,彩票收入近 61.7 亿美元,超过了前一年创纪录的 61.4 亿美元。

这是每个城市和城镇都想分一杯羹的生意。目前,所有 351 个市政当局都从彩票中获得资金。尽管没有售出任何彩票,但去年 38 个社区共获得了近 610 万美元。

根据马萨诸塞州市政协会的数据,2024 年该州向其市政当局提供的一般援助中有 91% 来自彩票销售。

但由于援助不是按彩票销售地点的比例发放的,因此彩票“在设计方式上是出了名的倒退”,研究员乔纳森·科恩 (Jonathan Cohen) 说道,他是《为了一美元和一个梦想:现代美国的州彩票》一书的作者。

作为研究的一部分,科恩发现,马萨诸塞州中部的哈佛社区每年获得约 170 万美元的援助,尽管多年来该镇没有售出一张彩票。哈佛镇目前只有一家持牌卖家:一家烛台保龄球馆;2023 年,该店报告的彩票销售额为 0 美元。

甚至在彩票成立之前,人们就担心资金向城市分配不均,这导致了最初的公式的产生,该公式一直持续到 2010 年。

彩票官员表示,他们对资金的分配没有发言权。

“我们与资金分配方式无关,”马萨诸塞州彩票执行董事马克·威廉·布拉肯 (Mark William Bracken) 说。“我们的工作只是运营者,然后是立法机关和州长……他们才是决定谁是受益人的人。”

几十年来,州政府官员一直在努力寻找更好的方式将资金分配给市政当局。 21 世纪初,波士顿联邦储备银行曾考虑改革地方援助,2013 年,时任州长德瓦尔·帕特里克 (Deval Patrick) 推动将收入水平纳入公式,以便向贫困社区提供更多援助,但未获成功。

但提议遭到了市政当局的抵制,他们担心自己会吃亏,这基本上停止了“关于改变地方援助方式以更加注重公平的讨论”,马萨诸塞州预算和政策中心的政策主管菲尼亚斯·巴克桑德尔 (Phineas Baxandall) 说,他曾在 90 年代担任审查地方援助分配的委员会成员。

州立法者仍在争论他们认为应该为所有社区提供公平份额的议题。

普利茅斯和巴恩斯特布尔州参议员苏珊·莫兰 (Susan Moran) 于 2023 年提交了一项法案,研究彩票援助公式的公平性,同时考虑到社区的中位数收入及其教育需求。该法案陷入停滞,莫兰没有竞选连任。

同样,伍斯特州众议员约翰·马奥尼在过去几年中也未能成功调整分配。

“我们只是希望它与这些城镇的销售成比例,”他说。

州长莫拉·希利表示,她将审查任何提交给她的立法。

然而,关于援助方案的争论忽略了对州立彩票的基本抱怨:它们不成比例地从较贫穷的社区吸引资金。学术研究发现,低收入人群、黑人和西班牙裔人群以及受教育程度有限的人群往往参与率较高,这引发了人们对州立彩票道德问题的担忧。

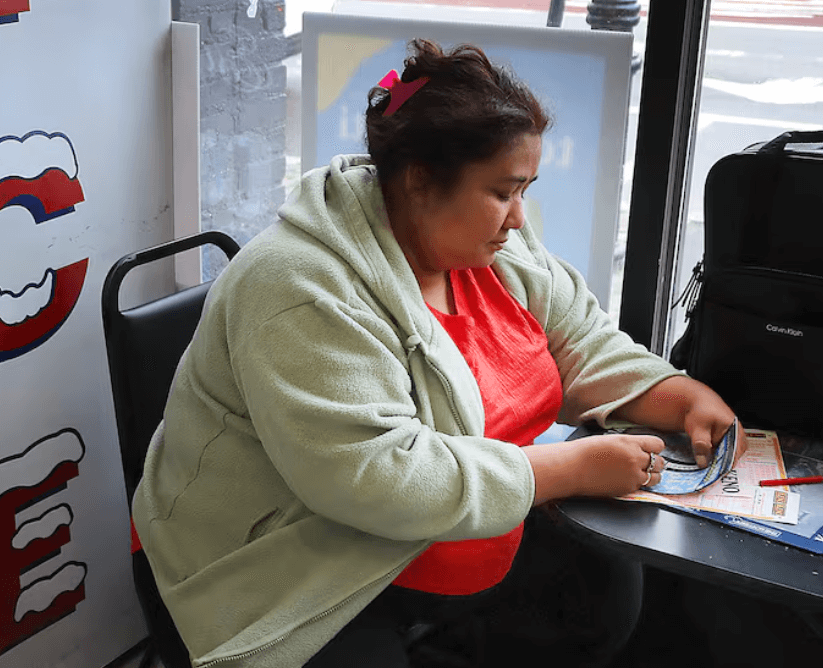

切尔西的莉莲·圣胡安记得华盛顿大道的超级市场卖出了一张价值 100 万美元的刮刮卡。几个星期以来,她和朋友一起买彩票的邻近家庭市场挤满了顾客,直到只有站立的空间。

“我们都有一个梦想,”圣胡安最近在便利店买了一张彩票后用西班牙语说道。这位四个孩子的母亲来自危地马拉,目前在芬威球场做清洁工作,她说如果她发了大财,她会买一套房子。

几分钟后,损失了 10 美元的 San Juan 将输掉的彩票扔进了垃圾桶,并决定去附近的另一家商店试试。

也许在那里,她会找到更好的运气。

《波士顿环球报》员工 Vince Dixon 和 Jeremiah Manion 对本报告做出了贡献。

这个故事由《波士顿环球报》的金钱、权力、不平等团队制作,该团队负责报道大波士顿地区的种族财富差距。

题图:Lilian San Juan 在切尔西的 Family Market 便利店刮了一张马萨诸塞州即开彩票。John Tlumacki/Globe 工作人员

附原英文报道:

Mass. residents are the biggest lottery players in the US. But the wealth isn’t shared equitably.

By Esmy Jimenez Globe Staff,Updated January 17, 2025

Lilian San Juan scratched an instant Massachusetts lottery ticket at the Family Market Convenience store in Chelsea.John Tlumacki/Globe Staff

For years, the Massachusetts State Lottery has been criticized for preying on low-income people by dangling the prospect of instant riches that only a very few will ever see.

But there is an equally big dose of inequity in how Massachusetts doles out the hundreds of millions it collects from the sale of lottery tickets: Low-income communities get back far less in state aid than their residents spend on the lottery, contrary to the original idea behind the lottery that poorer towns would benefit the most.

And repeated attempts to fix the system on Beacon Hill have gone for naught.

In Chelsea, for example, a predominantly Latino city with a median household income of about $72,000, vendors sold more than $50 million in tickets in 2023, but the city only received around $9.5 million, or roughly 18 percent of its sales. And in Brockton, a predominantly Black city with a similar household income, residents spent more than $120 million on lottery tickets, the fifth highest in the state. The city received roughly $24 million.

Meanwhile, the rural town of Harvard in Worcester County, with a median household income of $200,000, received nearly $2 million in aid yet did not have a single ticket sold there last year.

This disconnect comes down to how the local aid formula from the lottery, first conceived more than 50 years ago, was never adjusted to protect poorer communities when their allotments came up short.

Massachusetts is unique in the way it distributes lottery funds, in that most of the money is unrestricted rather than earmarked for specific purposes such as education or infrastructure. Georgia, for example, last year used $1.5 billion of lottery proceeds on education initiatives such as scholarships for students at state colleges and universities, free pre-k for 4-year-olds, and technology upgrades in local schools.

Here, while most of the money made from ticket sales goes to paying out the winners, about 19 cents on every dollar in sales goes to the state’s general fund, which is then distributed as aid to cities and towns. The payouts were initially based on population counts and property values in an attempt to help low-income cities make up for their lack of revenue or additional needs. That changed after the Great Recession when lawmakers switched to a system that combined lottery aid and additional assistance into one pot of money. Cities and towns would then get a percentage based on state revenue.

“What happens is, obviously, as the years keep going … communities that already receive less keep falling behind,” said Representative Antonio Cabral of New Bedford, who has for years filed bills to change the state’s myriad antiquated aid formulas. Gateway cities and rural communities especially struggle to fund local services and need more general aid, according to a report by the Massachusetts Municipal Association.

We need to “look at all the formulas that are in place and say, ‘OK, when was the last time this thing was revised or reformed?’” Cabral said. “The world has changed since ‘72 when the state sold its first lottery ticket.”

Today, the lottery is so entrenched residents can buy a scratch ticket while getting their cars fixed, washing clothes at a laundromat, or buying groceries. Massachusetts has the highest per capita spending on lottery tickets in the country, at about $839 per resident. Last fiscal year, the lottery had nearly $6.17 billion in revenue, eclipsing the record $6.14 billion from the year prior.

It’s a business that every city and town wants a piece of. Currently, all 351 municipalities receive funds from the lottery. Thirty-eight communities collectively received nearly $6.1 million last year despite not selling any lottery tickets.

According to the Massachusetts Municipal Association, 91 percent of the general aid the state sent to its municipalities in 2024 originated from lottery sales.

But because the aid is not doled out in proportion to where the tickets are sold, the lottery is “notoriously regressive in the way it’s designed,” said researcher Jonathan Cohen, author of “For a Dollar and a Dream: State Lotteries in Modern America.”

As part of his research, Cohen found the Central Massachusetts community of Harvard receives about $1.7 million in yearly aid, despite not having had a single lottery ticket sold in the town for many years. Harvard has one licensed seller in town now: a candlepin bowling alley; in 2023, it reported $0 in lottery sales.

Even before the lottery was established, there were concerns of inequitable distribution of funds to cities, leading to the creation of the original formula, which lasted until 2010.

Lottery officials said they have no say in how the money is divided up.

“We don’t have anything to do with the way the funds are distributed,” said Mark William Bracken, executive director of the Massachusetts State Lottery. “Our job is simply to be the operator, then the Legislature and the governor … they’re the ones that decide who gets to be the beneficiary.”

For decades, state officials have tried to find better ways to distribute funds to municipalities. In the early 2000s, the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston weighed in on reforming local aid, and in 2013, then-Governor Deval Patrick unsuccessfully pushed to include income levels in the formula to send more aid to poorer communities.

But proposals were met with resistance by municipalities that feared they would lose out, which has essentially ceased “the conversation about changing the way we could direct local aid to be more equity focused,” said Phineas Baxandall, a policy director at the Massachusetts Budget and Policy Center who served on a commission in the ‘90s that examined local aid distribution.

State legislators are still battling over what they believe should be a fair share for all communities.

State Senator Susan Moran of Plymouth and Barnstable filed a bill in 2023 to study the fairness of the lottery aid formula, taking into account the median incomes of communities and their education needs. The bill stalled and Moran did not run for reelection.

State Representative John Mahoney of Worcester likewise, over the last several years, has been unsuccessful in getting the distribution adjusted.

“We just want to have it proportionate to the sales in those towns,” he said.

For her part, Governor Maura Healey said she would review any legislation that makes it to her desk.

The arguments over the aid formula, however, look past the fundamental complaint about state-run lotteries: that they disproportionately draw from poorer communities. Academic research has found that people with lower incomes, Black and Hispanic people, and those with limited education tend to participate at higher rates, raising concerns about the ethics of state-run lotteries.

Lilian San Juan of Chelsea remembers when the Super Mart on Washington Avenue sold a $1 million scratch ticket. For weeks, the neighboring Family Market, where she bought tickets with her friends, filled up with customers until it was standing room only.

“We all have a dream,” San Juan said in Spanish recently after buying a ticket at the convenience store. Originally from Guatemala, the mother of four now works at Fenway Park cleaning and said she’d buy a home if she ever hits it big.

A few minutes later and $10 poorer, San Juan tossed the losing ticket into the trash and decided to try another store nearby.

Perhaps there, she’d find better luck.

Vince Dixon and Jeremiah Manion of the Globe Staff contributed to this report.

This story was produced by the Globe’s Money, Power, Inequality team, which covers the racial wealth gap in Greater Boston.