【中美创新时报2024 年 11 月 28 日编译讯】(记者温友平编译)塔夫茨大学的一个团队正在开发一种凝胶贴片,可以跟踪八个变量,包括步态和头部运动。《波士顿环球报》记者 Kay Lazar 对此作了下述报道。

从时尚的手表到闪亮的戒指,可穿戴传感器可以跟踪您越来越多的日常活动——心率、体温、睡眠时间等等——它们越来越小、越来越复杂、越来越昂贵。但一大群消费者可以从这种精确的追踪器中受益匪浅——患有慢性健康问题的老年人——却最不可能佩戴它们。

现在,塔夫茨大学的一个团队正在开发一种微小的凝胶状贴片,它可以实时检测认知能力下降和跌倒风险,不显眼,对老年人有吸引力,而且价格实惠。这个为期四年的新项目由 107 万美元的联邦拨款资助,其目标是制造一种贴片,帮助延长体弱的老年人(无论贫富)在家中安全生活的时间。

“对于穷人来说,诊断非常困难,”负责设计的塔夫茨大学生物、化学和电气工程教授萨米尔·桑库萨莱 (Sameer Sonkusale) 说。“让创新民主化很重要。”

对于监督这项研究的联邦管理人员来说,同样重要的是从该设备中收集的大量数据。塔夫茨大学团队将根据这些数据开发算法,以估计老年人的活动能力和认知能力如何随着时间的推移而下降——当医生办公室对某人进行不频繁的评估,并且是在一瞬间进行评估时,这些问题很容易被忽视。

希望这样的算法能帮助其他研究人员更清楚地了解正常的衰老迹象,而不是未来麻烦的信号。 最终,这种预警工具可以为护理人员提供更多见解以及干预时间。

“你从传感器获得的大量信息不仅仅是一次血压读数之类的。 它能够获得全天所有数据的时间序列,”资助塔夫茨研究的国家老龄研究所行为和社会研究部高级科学顾问乔纳森·金 (Jonathan King) 说。

到 2050 年,美国 65 岁及以上人口的数量预计将增加近 50%。美国人口参考局估计,到那时,这个年龄段的人将占美国人口的近四分之一。这推动了人们开发更复杂、更可靠的方法来跟踪老年人的健康状况。研究团队正在研究可以织入地毯和袜子中的微型数字传感器,以跟踪人的步态和活动能力。其他人正在研究贴片,这种贴片带有微型针头,可以插入皮肤下的液体中,就像血糖监测仪用于糖尿病一样,但可以测量一系列其他生物标志物,如电解质和某些蛋白质。

对于塔夫茨大学的发明,可以想象一个一角硬币大小的透明贴片,其质地与柔软的软糖一样。计划是让贴片(一个戴在颈后,另一个戴在胸前)能够跟踪八个变量,包括步态、姿势、头部运动、心率变异性和呼吸,研究人员认为这些变量与跌倒和认知能力下降的风险增加有关。

贴片将被设计用于检测微动作,例如坐在椅子上时的动作,“这是目前的可穿戴设备无法捕捉到的”,Sonkusale 说。

贴片中注入了类似牙线但可以检测运动的纤维,它包括一个微型发射器,类似于信用卡微芯片中的发射器,可以将数据无线发送到安全的计算机服务器,供研究人员分析。用户无需按按钮、阅读屏幕或解读技术。该团队设想最终的凝胶贴片可以将数据发送到用户的智能手机(如果他们使用)和他们的护理人员。

帮助老年人和残疾人独立生活的非营利组织 Mystic Valley Elder Services 的首席执行官 Lisa Gurgone 表示,传感器可能会有所帮助,但前提是它们不会吓到不懂技术的老年人。

“在 COVID 期间,我们向人们分发了 iPad,并培训他们如何使用,六个月后他们回到我们身边,仍然在盒子里,没有使用过,”Gurgone 说。技术“对他们来说不是直观的。他们需要很多支持。即使是一部基本的智能手机对他们来说也是如此令人难以承受。”

当然,到 2050 年,当今天精通技术的中年人安度黄金岁月时,对可穿戴传感器技术的舒适度将不再是一个问题。

但今天,它仍然处于最前沿。Gurgone 说,他们在项目中帮助过的老年人有时会表达对从他们身上收集的信息可能被用来对付他们的担忧和焦虑。

“人们担心‘我正在衰退,别人会发现我不能经常走动’,还有人担心‘我女儿会把我送进养老院’,”古尔戈内说。

老龄研究所的管理者金说,他的机构在审查研究项目时会考虑这些担忧。

“你可以拥有一个漂亮、奇妙的设备,但如果老年人不信任它,因为他们认为它在读他们的想法,或者做他们能想象到的它可能在做的事情,事情就会变得棘手,”他说。

桑库萨莱同意老年人可能不愿意使用可能显示他们心理健康正在衰退的设备。

“我希望用我们的凝胶贴片帮助老年人和他们允许的护理人员在跌倒等不良后果真正发生之前预测它们,”他说。“我不想把它当作诊断设备,而更想把它当作辅助设备。”

加州大学圣地亚哥分校可穿戴传感器中心主任 Joseph Wang 博士表示,尽管老年人使用可穿戴传感器具有明显的好处,但还有一个障碍:许多老年人只是更喜欢与健康专家进行个人接触。

尽管如此,Wang 博士对高科技可穿戴设备的未来充满信心,并引用了血糖监测贴片的成功经验。

“当我在 80 年代开始做这件事时,我们梦想着实现持续血糖监测,而这花了 20 年时间,”他说。

Wang 的实验室多年来一直致力于改进带有微针的微型贴片,这些贴片可以抽取佩戴者皮肤下的液体。最大的挑战和当前的目标是制造出可以持续使用两周以上而无需更换的贴片,就像今天的血糖贴片一样。

塔夫茨团队也在应对类似的挑战。研究人员预计他们的贴片将持续使用大约一周,然后才需要更换。但 Sonkusale 表示,他的团队强烈认为他们的产品应该是环保的。

他说,当旧贴片磨损时,贴片内的微型发射器可以取出,重新用于新贴片。

贴片本身呢?

“凝胶是可生物降解的,”他说。“它不会增加生物废物。”

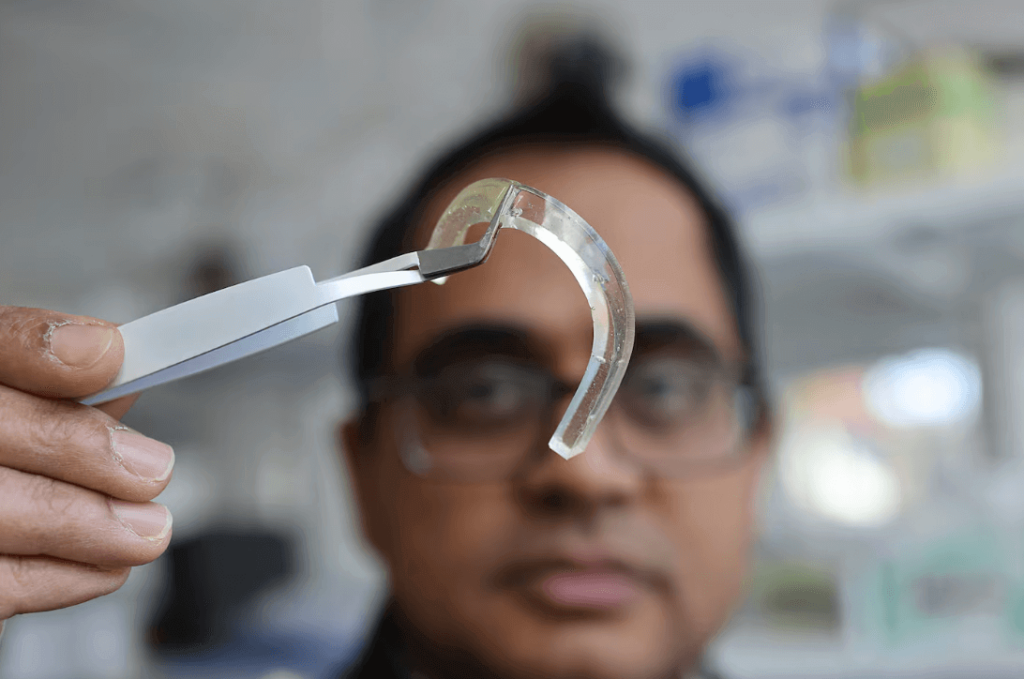

题图:在塔夫茨大学,Sameer Sonkusale 教授拿着一块凝胶,它被用来设计微型贴片,可以检测老年人的认知能力下降和跌倒风险。Suzanne Kreiter/Globe 员工

附原英文报道:

Tiny high-tech wearable aims to prolong time older adults live safely at home

A Tufts University team is developing a gel patch that tracks eight variables, including gait and head motion

By Kay Lazar Globe Staff,Updated November 26, 2024

At Tufts University, professor Sameer Sonkusale held a piece of the gel that is being used to design tiny patches that will detect cognitive decline and risk of falling in older adults.Suzanne Kreiter/Globe Staff

From sleek wristwatches to gleaming rings, wearable sensors that track a growing array of your daily activities — heart rate, body temperature, hours of sleep, and more — are getting smaller, more sophisticated, and pricier. But one large group of consumers who could greatly benefit from such precise trackers — older adults with chronic health problems — are the least likely to don them.

Now a team at Tufts University is developing a tiny, gel-like patch that would detect both cognitive decline and a person’s risk for falling in real time and be unobtrusive and appealing to older adults, as well as affordable. The goal of the new four-year project, funded by a $1.07 million federal grant, is to create a patch that would help prolong the amount of time frail seniors, rich or poor, would be able to live safely at home.

“It’s extremely challenging for people who are poor to get diagnosed,” said Sameer Sonkusale, a Tufts professor of biological, chemical, and electrical engineering, who is leading the design. “It’s important that innovation is democratized.”

Equally important to federal administrators overseeing the study is the treasure trove of data that will be amassed from the device. The Tufts team will develop algorithms from the data to estimate how an older adult’s mobility and cognitive abilities decline over time — problems that can easily fly under the radar when someone is being assessed infrequently, and in a snapshot of time, at a doctor’s office.

The hope is such algorithms will help other researchers more clearly understand normal signs of aging, versus signals of trouble ahead. Ultimately, such an early-warning tool could provide caregivers more insights as well as time to intervene.

“A lot of the information you would get [from the sensors] isn’t just like taking one blood pressure reading or something. It’s being able to have a time series of all of the data all through the day,” said Jonathan King, senior scientific adviser to the Division of Behavioral and Social Research at the National Institute on Aging, which is funding the Tufts study.

The number of Americans 65 and older is projected to increase by nearly 50 percent by 2050. By then, this age group will represent nearly one in four people in the United States, estimates the Population Reference Bureau. That’s fueling the push to create more sophisticated and reliable methods to track older adults’ health. Teams of researchers are responding by working on tiny digital sensors that can be woven into carpets and socks to track a person’s gait and mobility. Others are working on patches with minuscule needles that tap into the fluid just below your skin, the way glucose monitors work for diabetes, but to measure an array of other biomarkers such as electrolytes and certain proteins.

For the Tufts invention, picture a dime-sized, clear patch with the consistency of a squishy gummy candy. The plan is for the patch — one worn on the back of the neck, the other on the chest — to be able to track eight variables, including gait, posture, head motion, heart rate variability, and respiration, which researchers have linked to an increased risk of falling and cognitive decline.

The patch will be designed to detect micromovements, such as those you make while sitting in a chair, “things that aren’t captured by current wearables,” Sonkusale said.

The patch is infused with fibers that resemble dental floss but can detect motion, and it includes a miniature transmitter, similar to the one in a credit card microchip, that can wirelessly send data to secure computer servers for researchers to analyze. There will be no buttons to push, screens to read, or technology for users to decipher. The team envisions a final gel patch that could send the data both to a user’s smartphone (if they use one) and to their caregivers.

Lisa Gurgone, chief executive of Mystic Valley Elder Services, a nonprofit that helps older and disabled adults live independently, said sensors could be helpful, but only if they do not intimidate tech-challenged older adults.

“During COVID, we gave out iPads to people and trained them how to use them, and six months later they came back to us, still in the box, unused,” Gurgone said. Technology is “not intuitive for them. They need a lot of support. Even a basic smartphone is so overwhelming to them.”

Of course, by 2050, when today’s tech-savvy middle-agers are well-ensconced in their golden years, comfort levels with the technology of wearable sensors will fade as a concern.

But today, it’s still at the forefront. Gurgone said older adults they’ve helped in their programs sometimes express concern and anxiety about how information collected from them might be used against them.

“There is this fear that, ‘I am declining and someone can see that I can’t walk around as much,’ and there is this fear that, ‘My daughter will put me in a nursing home,’ ” Gurgone said.

King, the Institute on Aging administrator, said his agency considers those concerns when reviewing research projects.

“You can have a beautiful, wonderful device, but if older adults don’t trust it because they think it’s reading their minds, or any of the things that they can imagine it might be doing, it becomes tricky,” he said.

Sonkusale agrees that older adults may be reluctant to use devices that may show their mental health is declining.

“What I want to do with our gel patches is to help older adults and their permitted caregivers predict adverse outcomes such as falls before it actually happens,” he said. “I do not want to use this as a diagnostic device but more as an assistive device.”

Dr. Joseph Wang, director of the Center for Wearable Sensors at the University of California San Diego, said that despite potential clear benefits for the use of wearable sensors by older adults, one additional barrier remains: Many older people simply prefer personal contact with health professionals.

Still, Wang is bullish on the future for high-tech wearables, citing the success of glucose monitoring patches.

“We were dreaming when I started in the ‘80s about continuous glucose monitoring, and it took 20 years,” he said.

Wang’s lab has been working for years to refine the tiny patches with microneedles that tap the fluid just beneath a wearer’s skin. The biggest challenge, and current goal, is to create patches that can last more than two weeks without having to be replaced, as do today’s glucose patches.

The Tufts team is also homing in on a similar challenge. The researchers envision their patch will last about a week before having to be replaced. But Sonkusale said his team felt strongly their product should be environmentally friendly.

The tiny transmitter inside the patch, he said, can be popped out to be reused in a new patch when the old one is worn out.

And the patch itself?

“The gel is biodegradable,” he said. “It won’t add to the biowaste.”