在本特利大学,交易室是一个发射台

【中美创新时报2024 年 11 月 23 日编译讯】(记者温友平编译)学生经营的投资集团如何成为本特利大学沃尔瑟姆商学院的关键卖点。《波士顿环球报》记者Diti Kohli 对此作了下述报道。

本特利大学大一新生 Stella Case 大部分时间都不在教室、自助餐厅甚至宿舍里。中午或晚上,这位金融专业的学生很可能在交易室里。

这是一片电脑显示器和旋转椅的海洋,反映了华尔街的大厅,但位于史密斯学术技术中心的地下室。在那里,交易员与学生经营的本特利投资集团(BIG)一起学习股票市场的复杂性。他们用真钱玩。墙上的实时追踪器记录了学生管理的本特利捐赠基金份额:大约 140 万美元。

“交易室比图书馆好,”BIG 成员 Case 说。“这里就是家。”

大约 400 名学生定期参加会议,评估投资选择并投票决定是否投入资金,共有 1,600 名学生(超过本特利本科生人数的三分之一)表示今年有兴趣加入。这使得 BIG 成为沃尔瑟姆校区最大的课外活动。

该组织不仅吸引了在校学生,也吸引了未来的学生。在秋季开放日期间进行了 BIG 演示推介后,几位在金融领域工作的本特利家长评论说,该组织模仿了真实的投资推介节奏。Bentley 承诺教她职场的来龙去脉,并帮助她在毕业后找到工作,而 Case 本人也被 BIG 吸引。

“以前看到他们在台上演讲让我感到害怕,”18 岁的凯斯说。“但现在这是我在宾利最喜欢的部分。”

具有商业头脑的学校(包括宾利)长期以来一直优先考虑实践培训,以提高学生在大学毕业后被录用的机会。随着大学努力证明他们的教育仍然能让学生在就业市场上占据优势,这种做法已经远远超出了传统的实习范围。

宾利校友毕业十年后平均收入为 111,896 美元,高于高等教育咨询公司 HEA Group 调查的 3,800 所院校中的大多数。该校在“最佳”大学名单中一直名列前茅。根据经济智库 FreeOpp 的数据,从工商管理到人文学科,该校的所有学位都为学费投资带来了正回报。

“有很多学校的投资回报率为负数,尤其是硕士学位课程,”FreeOpp 研究员 Jon Hartley 说道。逆势而行可能成为“本特利的福利”。

在高等教育动荡时期,如此受欢迎的学生活动是本特利迄今为止避免加入新英格兰地区那些削减专业或完全关闭的陷入困境的大学行列的一种方式。虽然这些学校中有许多是小型文理学院,但整个行业都在努力吸引学生或说服他们学费物有所值。

本特利也未能免受这些因素的影响:自 2015 年以来,其总入学人数减少了 400 人,目前略多于 5,000 人。但公开数据显示,过去十年,总收入增长了约 8%,学费每年增加到约 84,000 美元。

课外活动,包括 BIG,是吸引学生并为他们提供课外资源的重要部分——教务长 Paul Tesluk 表示,这是 Bentley 利用其长期的商业优势,向那些试图证明大学学位越来越高的费用是合理的家庭展示自己差异化的一种方式。

从去年到现在,投资集团的参与人数猛增了 25%。

“我们的优势在于作为一所商学院的专注,”Tesluk 说。“体验式培训深深植根于我们心中。”

BIG 成立于1997年,最初由董事会投资25万美元,其成功与否取决于成员能否继续增加其在学校3.34亿美元捐赠基金中的份额。其他当地学校也有类似的组织:巴布森学院有一个27名学生的申请制投资俱乐部,管理着670万美元的资金;波士顿大学、塔夫茨大学、哈佛大学等也有这样的团体,但这些团体的规模或资金都不如本特利大学。

BIG 将其投资分为七个经济领域——例如技术和医疗保健——每个领域的领导职位都竞争激烈,令人垂涎。每个领域都有三名投资组合经理和最多六名分析师,以及其他不需要任命的成员。

在每周的宣传活动中,西装革履的学生向同事们推销对市值至少20亿美元的上市公司的长期股权投资,目标是持有这些股份多年。他们先是找出债务、资本支出和诉讼支出的数字,然后一大群成员开始挑刺并提出问题。如果回答得足够充分,说服了三分之二的成员,那么这只股票就可以加入投资组合。

10 月,学生们将计算巨头 Nvidia 添加到了他们的 25 家公司组合中。但并不是每一次选择都如此顺利:他们选择的投资 Lululemon 和机上连接公司 Gogo 近年来都亏损了。据该基金的一位投资组合经理称,自 1997 年以来,该基金每年增长约 7%,而同期股市主要基准标准普尔 500 指数的回报率为 10%。

但是,如果 BIG 的交易看起来风险太大,房间里总有一位资深人士:拥有 35 年投资经验的 BIG 教师顾问 Alain Chinca。但作为所有财务决策的最终决定者,Chinca 很少发现自己需要干预。

“学生们会自我纠正。我不认为自己是训练轮。我把自己看作护栏。因为,”他指着房间里的 BIG 成员说,“这就是他们。”

BIG 总裁 Raine Spearman 说,这一切有时感觉比课堂本身更能体现大学经历的实质。

“我们大部分时间都待在交易室里,准备或审查宣传,我们喜欢这样,”他说。“这是在 Bentley 工作的重要部分。”

学生在 BIG 的时间通常会以超出预期的职位结束:大多数投资组合经理都是大三学生,而不是大四学生,以“确保团队的长久性”,该公司运营副总裁兼技术投资组合经理 Max Provencher 说。到大学最后一年,学生通常会有来自大型银行和金融公司的就业机会。

“对我们很多人来说,投资集团已被证明是艰苦劳动力市场中的差异化因素,”20 岁的大三学生 Provencher 说道,他自己现在正在面试实习。(他在 BIG 的前任收到了花旗银行销售和交易部门的录用通知。)“这里的人均大学数量比世界上任何地方都多。但在这里,你可以在投资集团比在课堂上更快地学习金融知识。”

Bentley 教授、富达前投资组合经理 Joe Wickwire 表示,这在波士顿金融服务行业求职时非常有用。BIG 允许学生承担风险并获得实际回报,这向招聘经理证明“他们可以勇敢而聪明”。

“他们进入职场时不会像其他知名大学那样带着优越感,”Wickwire 说道。“但技能是一样的。”

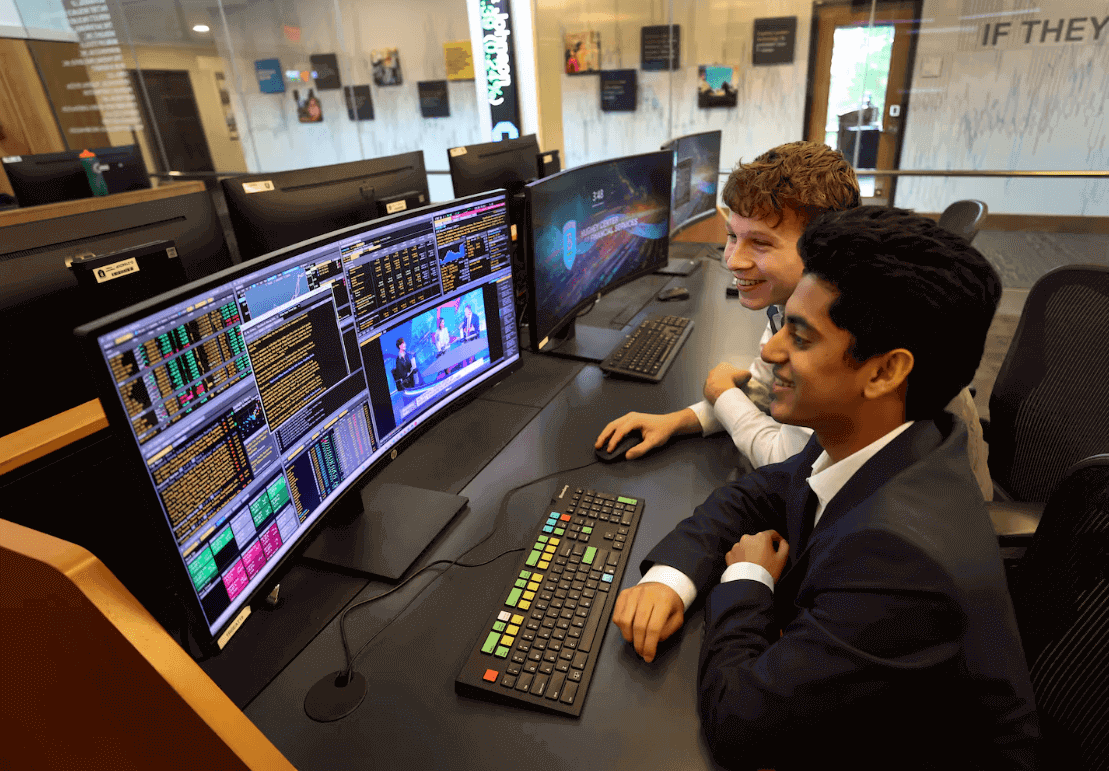

题图:Sai Hejmadi(左)和 Aidan Swenson,本特利投资集团成员,在学校的交易室。David L. Ryan/Globe 员工

附原英文报道:

At Bentley University, the trading room floor is a launching pad

How a student-run investment group became a key selling point for the Waltham business school

By Diti Kohli Globe Staff,Updated November 16, 2024

Sai Hejmadi (left) and Aidan Swenson, members of the Bentley Investment Group, in the school’s trading room.David L. Ryan/Globe Staff

WALTHAM — Bentley University freshman Stella Case does not spend most of her time in the classroom, the cafeteria, or even the dorms. Noon or night, the finance major is likely in the trading room.

It’s a sea of computer monitors and swivel chairs that mirrors a Wall Street floor but sits in the basement of the Smith Academic Technology Center. There, traders learn the intricacies of the stock market with the student-run Bentley Investment Group, or BIG. And they’re playing with real money. On the wall, a live tracker tallies the portion of Bentley’s endowment overseen by the students: roughly $1.4 million.

“The trading room is better than the library,” said Case, a member of BIG. “It’s home.”

Around 400 students regularly attend meetings to assess investment options and vote on whether to put money down, and 1,600 students in total — more than one-third of Bentley’s undergraduate population — expressed interest in joining this year. That makes BIG the largest extracurricular on the Waltham campus.

The organization is not only a magnet for current students but a draw for prospective ones. After a BIG demo pitch during the fall open house, a few Bentley parents who work in finance remarked on how closely the organization mimicked the cadence of an authentic investment pitch. Case herself was drawn to Bentley by BIG’s promise to teach her the ins and outs of the working world and help her secure a job after graduation.

“It used to be intimidating for me to see them pitch on stage,” said Case, 18. “But this is my favorite part of Bentley now.”

Business-minded schools — Bentley included — have long prioritized hands-on training to raise students’ chances of being hired out of college. What that looks like has evolved far beyond traditional internships, as universities work to prove their education still gives students a leg up in the job market.

Bentley alumni earn $111,896 on average a decade after graduation, more than most of the 3,800 institutions surveyed by higher education consultancy The HEA Group. The school consistently ranks highly on “best of” college lists. And all of its degrees — from business administration to the humanities — provide a positive return on investment from tuition, according to data from the economics think tank FreeOpp.

“There are a lot of schools out there that have negative ROI degrees, particularly in master’s degree programs,” said Jon Hartley, a FreeOpp research fellow. Going against that grain could be a “perk for Bentley.”

At a tumultuous time in higher education, such a highly popular student activity is one way Bentley has so far avoided joining the cohort of struggling colleges in New England that have slashed majors or closed altogether. While many of those schools are small liberal arts colleges, the industry broadly is struggling to attract students or convince them tuition is worth the payoff.

Bentley hasn’t been immune to these forces: Its total enrollment has dropped by 400 students since 2015, to just over 5,000 now. But total revenue is up around 8 percent in the past decade, public data shows, with tuition increasing to around $84,000 annually.

Extracurriculars, including BIG, are a big part of enticing students and offering them resources outside of class — one way Bentley has used its longtime business niche to differentiate itself to families trying to justify the ever-larger expense of a college degree, said provost Paul Tesluk.

Participation in the investment group shot up by 25 percent between last year and now.

“A strength of ours is a focus as a business university,” Tesluk said. “Experiential training is deeply ingrained in us.”

BIG began with a $250,000 investment from the Board of Trustees in 1997, and its success is measured by members’ ability to continue growing its portion of the school’s $334 million endowment. Other local schools have similar organizations: Babson College has a 27-student, application-only investment club that manages $6.7 million; groups also exist at Boston University, Tufts, Harvard, and elsewhere, though few of those are as large, or well -endowed, as Bentley.

BIG has split its investments into seven sectors of economy — technology and health care, for example — and leadership positions within each sector are competitive and coveted. Each sector has three portfolio managers and up to six analysts, plus other members who do not need to be appointed.

In weekly pitches, students in suits and ties sell their colleagues on long-term equity investments in public companies with a market cap of at least $2 billion, with the goal of keeping the stake for many years. They tease out figures on debt, capital expenditures, and litigation payouts, before the crowd of members pokes holes and asks questions. Answer adequately enough to convince two-thirds of the group, and the stock in question can join the portfolio.

In October, the students added computing powerhouse Nvidia to their 25-company cohort. Not every pick goes so well: Chosen investments in Lululemon and the in-flight connectivity company Gogo lost money in recent years. Since 1997, the fund has grown by roughly 7 percent annually, according to one of its portfolio managers, compared to a 10 percent return for the stock market’s main benchmark, the Standard & Poor’s 500, during that period.

But should a trade at BIG look too risky, there is always one veteran in the room: Alain Chinca, BIG’s faculty adviser with 35 years of investment experience. But as the final word on all financial decisions, Chinca rarely find himself having to intervene.

“The students self-correct. I don’t see myself as a training wheel. I see myself as a guardrail. Because this,” he said, pointing to BIG members around the room, “is all them.”

BIG president Raine Spearman said it can all sometimes feel like a more substantive part of the college experience than the classroom itself.

“We spent most of our time in the trading room, prepping or reviewing pitches, and we like it that way,” he said. “This is a big part of being at Bentley.”

A student’s time within BIG often ends with an offer beyond it: Most portfolio managers are juniors, not seniors, to “ensure the longevity” of the group, said Max Provencher, its vice president of operations and technology portfolio manager. By the final year of college, students typically have job prospects from major banks and financial firms.

“The investment group for a lot of us has proven to be that differentiator in a hard labor market,” said Provencher, a 20-year-old junior interviewing for internships himself now. (His predecessor at BIG has an offer on the sales and trading desk at Citibank.) “There’s more colleges per capita here than anywhere in the world. But you can learn the finance stuff here faster at the investment group than in the classroom.”

It can come in handy when hunting for jobs in Boston’s financial services industry, said Joe Wickwire, a Bentley professor and former portfolio manager at Fidelity. BIG allows students to play with risk and see real returns, proof to hiring managers that “they can be scrappy and smart.”

“They do not come into the workforce with an air of entitlement that can sometimes come from other high-profile universities,” Wickwire said. “But the skillset is the same.”