【中美创新时报2024 年 8 月 30 日编译讯】(记者温友平编译)对于另外两所马萨诸塞州学校来说,去年最高法院终止大学录取平权行动的裁决将导致学生群体多样性降低的预测似乎正在成为现实。塔夫茨大学和阿默斯特学院周五都表示,新生的种族多样性有所下降。《波士顿环球报》记者丹尼·麦克唐纳(Danny McDonald)和海伦娜·格塔洪-霍金斯(Helena Getahun-Hawkins)对此作了下述报道。

目前尚不清楚这些学校以及麻省理工学院为何会出现多样性下降——平权行动的结束是否让有色人种学生更难被录取,还是因为不鼓励他们申请而导致学生人数减少。

随着美国各大高校秋季学期的临近,随着来自其他院校的多元化数据不断涌现,最高法院裁决的全面影响尚未显现。

马萨诸塞大学阿默斯特分校是该州大学系统的旗舰校区,该校最近宣布了有史以来最多元化的新生班,此前学校领导表示,他们积极招收有色人种学生,以克服因裁决而导致的申请人数下降。

在梅德福,塔夫茨大学艺术与科学学院和工程学院招生与招生管理院长 JT Duck 称有色人种学生的减少是“令人失望的下降”。

“继去年 6 月最高法院禁止将种族和/或民族本身作为决定是否录取申请人的因素之后,我们当时表示,我们当然会尊重法律,但大学对包容性卓越的愿景仍然是至关重要且坚定不移的,”他在一份声明中表示。

相关:麻省理工学院称,由于最高法院决定终止平权行动,新生班级的多样性下降

在塔夫茨大学,今年新生班级中有色人种学生从前一年的约 50% 下降到 44%。

在马萨诸塞州西部,阿默斯特学院也报告称,新生班级的多样性不如近年来。去年,47% 的新生认为自己是有色人种学生。对于 2028 年的新生,这一数字下降到 38%。

与此同时,麻省理工学院本月早些时候报告称,16% 的本科生认为自己是黑人、西班牙裔、美洲原住民或太平洋岛民,低于近年来的 25%。但随着新学年的到来,大多数学院和大学尚未公布其新生班级的人口分布情况。

相反,马萨诸塞大学阿默斯特分校表示,其 5,300 多名新生中,近 39% 是有色人种。去年,该大学报告称这一数字为 36%。

去年,最高法院在大学录取中终止了基于种族的平权行动,推翻了近半个世纪的先例,剥夺了精英大学保持校园多元化所必需的工具。

根据去年提交给法院的研究和分析,这项裁决是在两起挑战哈佛大学和北卡罗来纳大学教堂山分校招生实践的诉讼中做出的,预计将导致被美国最负盛名的学校录取的黑人、西班牙裔和土著学生数量大幅下降。

塔夫茨大学社会学教授娜塔莎·瓦里库 (Natasha Warikoo) 曾撰写过有关大学录取平权行动的书籍,她担心,更少的代表性不足的学生将有机会从塔夫茨教育中受益。

“我们不能教育不在我们课堂上的学生,”她说。

虽然随着学生进入大学并进入劳动力市场,平权行动的结束将很难看出其长期影响,但“从通过州公民投票或立法行动实施禁令的州中,我们可以得到一些令人警醒的教训,”瓦里库说。

1996 年,加利福尼亚州举行了一场公投,结束了大学录取中的平权行动。自那以后,研究表明,该州的学院的多样性下降了。

代表性不足的少数族裔学生更有可能就读加州大学系统中排名较低的大学,这些大学毕业率较低,导致学生不太可能成功完成学业。研究还表明,这些少数族裔学生主修 STEM 领域的可能性较小。Warikoo 说,这些综合因素似乎会影响他们的工资。

针对这些发现,加州已投入资金,试图提高其大学的多样性。然而,Warikoo 说,“我们能在多大程度上弥补多样性的下降还有待观察”。

在阿默斯特,管理人员于周四下午向学院社区发送了一封信,称“我们将根据法律继续并深化我们正在进行的努力,以接触和招收来自各种背景和经历的学生。”

“这个过程需要时间,但我们非常有信心,我们将继续建立一个反映我们周围世界多样性的社区,”信中写道。

对于阿默斯特学院政治学和性别研究教授 Amrita Basu 来说,决定终止大学招生中的平权行动令人十分担忧。她担心校园里的多样性会减少,而她认为多样性是“学习不可或缺的”,去年夏天她与他人合写了一封信,向学生们表明阿默斯特学院的教师非常重视多样性。

“背景的多样性往往与生活经历和知识的多样性相关,”Basu 在周五的电话采访中说道。“因此,学生群体越多样化,他们就越能谈论一系列问题。”

现在,她曾经最担心的事情——阿默斯特学院的多样性减少——似乎已经成真了。

在城镇的另一边,马萨诸塞大学阿默斯特分校的发言人 Melinda Rose 承认,在最高法院作出裁决后,学校“担心有色人种学生不太愿意申请,担心他们不会被录取。”

“马萨诸塞大学阿默斯特分校招生人员加倍努力鼓励潜在学生及其家人提交申请,”罗斯在一封电子邮件中说。“因此,该校收到的来自……代表性不足的群体的申请增加了 11%。从那时起,马萨诸塞大学阿默斯特分校多年来实施的整体审查流程对我们有利,通过该流程,申请人将在个性化的背景下进行考虑。”

城市研究所高等教育政策主任布莱恩·库克表示,入学人数只是去年最高法院裁决影响的“一部分”。

库克表示,仍有一些悬而未决的问题:一些学校的多样性下降是否反映了申请这些学校的多元化学生人数减少?还是说,通过现在无法将种族作为一个因素的招生程序申请的多元化申请人比例相同?

“你没有得到完整的画面,”他说。

在最高法院的裁决中,六名保守派法官裁定哈佛大学和北卡罗来纳大学教堂山分校的招生做法违反了宪法第十四修正案的平等保护条款。三名自由派法官持不同意见。哈佛大学校友、前校监委员会成员凯坦吉·布朗·杰克逊法官回避了哈佛大学的案件。

大学招生案围绕一个由政治分歧驱动的情绪化问题:种族在现代社会中的作用。

这项裁决是近十年来由反平权行动组织“公平录取学生”发起的诉讼的高潮。2014 年,该组织提起了两起诉讼,一起指控哈佛大学的招生做法非法歧视亚裔美国申请者,另一起指控北卡罗来纳大学教堂山分校歧视亚裔和白人。在公平录取学生在下级法院败诉后,该组织向最高法院上诉。

大学领导表示,将种族作为录取过程中的众多因素之一,是招收因 K-12 教育中的系统性不平等而处于不利地位的学生的最佳工具。

甚至在裁决之前,精英学校的管理人员就一直在努力扩大与非营利组织和社区组织的合作伙伴关系,这些组织为代表性不足和低收入学生提供服务。他们还增加了论文问题,让申请人阐述文化、生活经历和社区如何影响他们的身份和抱负。

Globe 员工 Mike Damiano 和 Hilary Burns 对本报告做出了贡献。

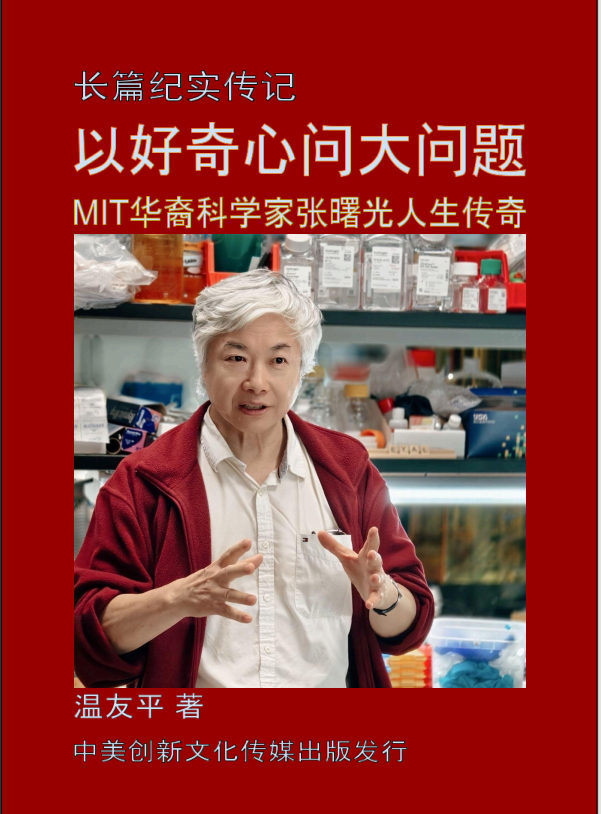

题图:塔夫茨大学新生中有色人种学生的比例比去年下降了 6 个百分点。Jessica Rinaldi

附原英文报道:

Fewer students of color at some Mass. colleges after Supreme Court ruling

By Danny McDonald and Helena Getahun-Hawkins Globe Staff and Globe Correspondent,Updated August 30, 2024

The percentage of students of color of Tufts University’s freshman class has dropped by 6 percentage points from last year.Jessica Rinaldi

For two more Massachusetts schools, predictions that a Supreme Court decision last year that ended affirmative action in college admissions would result in less diverse student bodies appear to be materializing. Both Tufts University and Amherst College said Friday that the racial diversity of their incoming freshman classes has decreased.

It’s unclear why these schools, along with The Massachusetts Institute of Technology, saw drops in diversity — whether the end of affirmative action made it harder for students of color to get admitted or if fewer students applied because they were discouraged to.

As the fall semester begins to ramp up for US colleges, a full picture of the ramifications of the Supreme Court ruling has yet to materialize as diversity figures continue to trickle in from other institutions.

The University of Massachusetts Amherst, the flagship campus of the state’s university system, recently announced its most diverse incoming class ever, after school leaders said they aggressively recruited students of color to overcome an expected drop in applications because of the ruling.

In Medford, JT Duck, Tufts dean of admissions and enrollment management for the School of Arts and Sciences and the School of Engineering, called the decrease in students of color a “disappointing drop.”

“Following the Supreme Court’s decision last June barring the use of race and/or ethnicity in and of itself as a factor in deciding whether to admit an applicant, we said then that we would, of course, respect the law, but the university’s vision of inclusive excellence continues to be mission critical and unwavering,” he said in a statement.

Related: MIT says incoming class is less diverse as a result of Supreme Court decision to end affirmative action

At Tufts, students of color in this year’s freshman class dropped to 44 percent, down from roughly 50 percent the prior year.

In Western Massachusetts, Amherst College also reported an incoming undergraduate class that is less diverse than in recent years. Last year, 47 percent of incoming freshmen identified as students of color. For the incoming class of 2028, that number dipped to 38 percent.

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology, meanwhile, reported earlier this month that 16 percent of enrolling undergraduates identify as Black, Hispanic, Native American, or Pacific Islander, down from 25 percent in recent years. But as the new academic year ramps up, most colleges and universities have yet to divulge the demographic breakdown of their incoming classes.

Conversely, UMass Amherst said almost 39 percent of its 5,300-plus incoming students are people of color. Last year, the university reported that figure was 36 percent.

The Supreme Court ended the use of race-based affirmative action last year in college admissions, overruling nearly half a century of precedent and depriving selective universities of a tool they say is essential for keeping their campuses diverse.

The ruling, in two lawsuits challenging admissions practices at Harvard University and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, was expected to cause a significant decline in the number of Black, Hispanic, and Indigenous students admitted to the nation’s most prestigious schools, according to research and analyses presented to the court last year.

Natasha Warikoo, a professor of sociology at Tufts University, who’s written books about affirmative action in college admissions, worries that fewer underrepresented students will have the opportunity to benefit from a Tufts education.

”We can’t educate students who are not in our classroom,” she said.

While the long-term impact of the end of affirmative action will be hard to discern as students move through college and into the labor market, “there are some sobering lessons from states that have had bans implemented through state referenda or legislative action,” Warikoo said.

In 1996, California held a referendum that ended affirmative action in college admissions. Since then, studies have shown that diversity in its state colleges declined.

Underrepresented minority students are more likely to attend lower ranked colleges within the University of California system, whose lower graduation rates make students less likely to successfully complete their education. Studies have also shown that these minority students are less likely to major in STEM fields. These compounding factors, Warikoo said, seem to impact their wages down the line.

In response to these findings, California has invested money into trying to boost diversity at its universities. Nevertheless, Warikoo said, “it remains to be seen how much we can compensate for that decline” in diversity.

At Amherst, administrators sent a letter Thursday afternoon to the college’s community saying that “we will continue and deepen our ongoing efforts — in accordance with the law — to reach and recruit students from a wide range of backgrounds and experiences.”

“This process will take time, but we are very confident that we will continue to build a community that reflects the diversity of the world around us,” the letter reads.

For Amrita Basu, a professor of political science and gender studies at Amherst College, the decision to end affirmative action in college admissions is greatly concerning. Fearing that diversity, which she considers “indispensable to learning,” would decrease on campus, she coauthored a letter last summer affirming to students how much Amherst’s faculty values diversity.

”Diversity of backgrounds is often correlated with diversity of life experience and knowledge,” Basu said in a phone interview Friday. “So the more diverse the student body, the more they are able to speak to a range of issues.”

Now, it appears that what she once feared the most — a decrease in diversity at Amherst College — has materialized.

Across town, Melinda Rose, a UMass Amherst spokesperson, acknowledged that following the Supreme Court decision the school “had concerns that students of color would be less inclined to apply, fearing they would not be accepted.”

“UMass Amherst admission staff redoubled their efforts to encourage prospective students and their families to submit applications,” Rose said in an email. “As a result, the university saw an 11 percent increase in applications from … underrepresented populations. From there, the holistic review process that UMass Amherst has had in place for years, through which applicants are considered in an individualized context, worked to our advantage.”

Bryan Cook, director of higher education policy at the Urban Institute, said enrollment numbers are “just one piece” of the impact of last year’s Supreme Court decision.

Cook said there are still open questions: Is the decline in diversity at some schools a reflection of fewer diverse students applying to the schools? Or is it the same share of diverse applicants applying through an admissions process that is now unable to use race as a factor?

”You’re not getting a complete picture,” he said.

In the Supreme Court decision, the court’s six conservative justices ruled that Harvard’s and UNC Chapel Hill’s admissions practices violated the equal protection clause of the Constitution’s 14th Amendment. The court’s three liberal justices dissented. Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, a Harvard alum and former member of the school’s Board of Overseers, recused herself from the Harvard case.

The college admissions case centered on a highly emotional issue driven by political divisions: the role of race in modern society.

The ruling was the culmination of nearly a decade of litigation initiated by an anti–affirmative action group called Students for Fair Admissions. In 2014, it filed two lawsuits, one alleging that Harvard’s admissions practices illegally discriminated against Asian American applicants, the other accusing UNC Chapel Hill of disadvantaging Asians and whites. After Students for Fair Admissions lost both cases in lower courts, it appealed to the Supreme Court.

College leaders have said that using race as one of many factors in the admissions process was the best tool available to enroll students disadvantaged by systemic inequities in K-12 education.

Even before the ruling, administrators at selective schools had been working to expand partnerships with nonprofits and community organizations that work with underrepresented and low-income students. They also added essay questions to allow applicants to expound on how culture, life experiences, and community have influenced their identities and ambitions.

Mike Damiano and Hilary Burns of Globe staff contributed to this report.