【中美创新时报2024 年 6 月 17 日编译讯】(记者温友平编译)杰琳·马塞多(Jaylene Macedo)是波士顿公立学校 5,000 多名学生之一——占该学区人口的 10% 以上——他们在本学年的某个时候经历过无家可归。这是该学区创下的最高水平,自 2021-2022 学年以来,这一令人不安的趋势一直在上升。《波士顿环球报》记者克里斯托弗·哈夫克(Christopher Huffaker)对此进行下述详细报道。

墙上的油漆很脏,而且剥落了,窗户朝向蓝山大道,房间里充满了街上打架的声音、车辆呼啸而过的声音以及人们说话和喊叫的声音。

当时 6 岁的杰琳·马塞多(Jaylene Macedo)在混乱中无法集中注意力。这位一年级学生与她的母亲娜塔莉亚·马塞多(Natalia Macedo )和妹妹阿娃(Ava )住在罗克斯伯里无家可归者收容所的一间狭小的房间里,里面有两张床。

她感觉不安全,经常爬到妈妈的床上,直到睡着。几个月来,她一直问妈妈:“我们什么时候才能有自己的房子?”或“我什么时候才能拿回我的房间?”

杰琳·马塞多是波士顿公立学校 5,000 多名学生之一——占该学区人口的 10% 以上——他们在本学年的某个时候经历过无家可归。这是该学区创下的最高水平,自 2021-2022 学年以来,这一令人不安的趋势一直在上升。在全国范围内,没有永久住房的学生——无论是像马塞多这样的收容所,还是街头,还是与家人或朋友一起沙发冲浪——往往都会遭受严峻的后果。

数据显示,他们在州考试中的表现明显差于同龄人,按时毕业的频率也较低。全州范围内,大约五分之一的无家可归学生辍学。

为什么情况变得如此糟糕?

“一场完美风暴,”非营利组织 Higher Ground 的负责人布兰迪·布鲁克斯(Brandy Brooks)说,该组织与 BPS 合作开展住房工作并帮助 Macedos 一家安置住房。

租金创下历史新高,高于全国大多数地方。疫情高峰期实施的驱逐禁令已经到期,许多拖欠房租的人被迫搬离。大量移民涌入,其中许多是无人陪伴的年轻人,他们也进入了学校系统,挤满了该州的紧急避难所。在拨出更多联邦资金之前,波士顿住房管理局不再提供联邦住房补贴(即第 8 条代金券)——就在学区向无家可归家庭提供这些补贴的努力开始取得成果的时候。

无家可归一直是 BPS 面临的一个挑战,最近几年有 4,000 多名无家可归的学生入学。该学区长期以来一直致力于满足这些学生的一些需求,每年都会举办冬季大衣活动和食品储藏室。

但在过去十年中,解决学生无家可归问题已成为人们关注的焦点,东波士顿高中的无家可归者联络员尼娜·盖塔 (Nina Gaeta) 表示,他们努力帮助无家可归的家庭支付食物、保暖衣物和洗漱用品等必需品,同时也帮助他们安置住房。

其中一个合作伙伴关系是与波士顿家庭援助组织合作的早期无家可归干预计划,该计划致力于通过将家庭与可以提供财务、法律甚至健康援助等服务的组织联系起来,防止家庭无家可归,并自 2022 年以来帮助了 900 多个家庭,负责支持无家可归学生的机会青年部负责人布莱恩·马克斯 (Brian Marques) 表示。

但马奎斯表示,该学区最大的成功是自 2021 年以来帮助安置了 1,600 多个家庭。波士顿住房管理局与学区达成协议,向 BPS 家庭发放可用的住房券,而学区和波士顿家庭援助组织等合作伙伴则帮助家庭寻找住房,并提供资金帮助支付经纪人费用和保证金。该学区还利用市政府资助的代金券为一些家庭提供住房,并与住房管理局合作,让这些家庭能够入住公共住房。

“如果我们不为他们提供住房,这些数字将是天文数字,”马奎斯说。

多切斯特的阿尔宾·卡西拉 (Albin Casilla) 是该学区帮助安置的一名学生。卡西拉于 2019 年从多米尼加共和国移民,当时他 14 岁。他、他的母亲和他的兄弟与家人住在一起——六个人合住一间一居室的公寓。 (根据联邦法律,“合住”或因经济困难而与他人合住,属于无家可归。)

一些家庭成员睡在客厅,但卡西拉为了避免家庭成员之间频繁的争吵和大喊大叫,更喜欢小衣柜的安全和隐私。他不得不蜷缩成胎儿的姿势躺下睡觉,并在昏暗的衣柜灯光下努力学习。他说他的背仍然很疼,但这比处理家庭矛盾要好。

与许多无家可归的学生不同,卡西拉从未缺课,尽可能少地待在狭窄的公寓里。

“当时我确实想上学,”卡西拉说。 “但与此同时,当家里发生意外时,很难集中注意力。”

卡西拉感到很尴尬,不想告诉任何人他的生活状况,但当学校辅导员听说这件事时,她帮助他的母亲获得了第 8 节代金券和多切斯特的一套公寓。卡西拉刚刚在麻省大学波士顿分校完成了大一学年,现在仍住在那里。

卡西拉感谢 BPS 对他的帮助,但希望学校能做更多工作来宣传可用的支持,以便其他人尽早了解。

就马塞多一家而言,杰琳的祖母卖掉了他们住的房子后,马塞多一家无家可归,娜塔莉亚决心尽快为女儿找到新住处,并前往杰琳的学校寻求帮助。

“如果我和学校谈谈,也许他们能帮助我,尤其是因为我女儿在那里上学,”马塞多想。“没人想看到孩子住在收容所或无家可归。”

学校的家庭联络员弗朗西斯卡·格瓦拉(Francisca Guevara)和马塞多坐下来,告诉她,他们一家会渡过难关的。他们一起填写了申请表,马塞多与 Higher Ground 取得了联系,后者花了几个月的时间与她合作——帮助她收集文件、为她联系住房线索,并确保所有文件都井然有序。与此同时,格瓦拉帮助 Macedos 一家从学校获得了他们需要的所有支持,无论是衣服、清洁用品还是支持性的话语。

“我从来不知道 BPS 会如此有帮助,”马塞多说。“她帮助了很多家庭。”

三月份,在 Jaylene 七岁生日后不久,马塞多接到了电话:在收容所住了七个月后,他们终于在布莱顿的补贴住房里有了家。

“孩子们的脸真的让我很开心,”马塞多说。

东波士顿高中的无家可归者联络员盖塔说,这种感觉似乎遥不可及。她可以帮助那些无人陪伴而来到美国的学生申请现有的住房,但她自己却无法建造新的住房。

“感觉很糟糕,”盖塔说。“你想为他们解决这个问题。但你知道你做不到。”

不过,盖塔说,学校会尽其所能支持贫困家庭。大约十年前,在对无家可归的学生进行调查后,东波士顿高中开设了一个食品储藏室和一个衣柜,并为学生提供洗衣设备。学校配备了微波炉,这样那些正在工作而没有时间吃饭的学生就可以多吃一些热饭。盖塔说,这很有效。她学校的许多无家可归的学生都住在波士顿,没有家人,靠工作养活自己,但他们仍然来上学。

“他们来的时候很累,但他们还是来了,”盖塔说。“他们可能会缺课,可能会有缺课问题,但他们仍然来上学。他们在努力。”

州数据显示,无家可归的学生的结果比同龄人要差得多。在大多数年级和科目中,无家可归的 BPS 学生在州 MCAS 考试中达到年级要求的比例只有同龄人的一半。约有三分之一的学生未能按时毕业;其中一些学生在五年或更长时间后毕业,但许多人辍学。在全州范围内,差距甚至更大。

Jaylene 和她的妹妹最近被分配到新社区的一所新学校 Edison K-8。他们把公寓布置得像自己的一样,装饰起来,买了一张新沙发,还养了一只宠物——一条养在粉色鱼缸里的小红鱼。Jaylene 不再害怕睡在床上。

马塞多说,她希望女儿们正常成长,知道她在她们身边,善待他人,珍惜生命,“因为你可以拥有一切,也可以在一秒钟内失去一切。”她说,她很幸运能处于现在的境地。

对于像 Higher Ground 的 Brandy Brooks 这样的倡导者来说,这就是问题所在。

“我们怎样才能不只是靠运气呢?”她最近问马塞多。“还有许多其他家庭和你们一样……我们如何确保每个人都能得到同样的好运?”

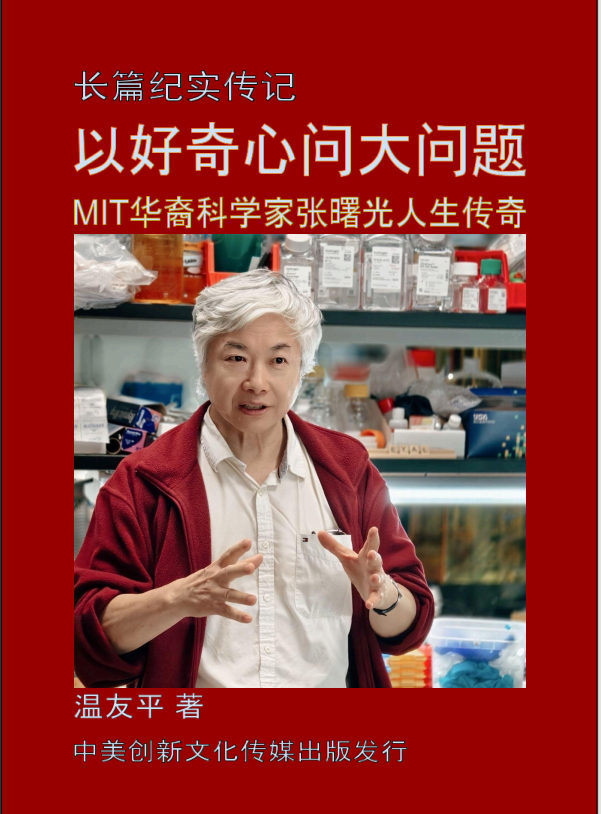

题图:Jaylene Macedo 在她家位于布莱顿的新公寓附近的操场上玩耍。她、她的姐姐和母亲 Natalia Macedo 无家可归了七个月,然后才搬进了布莱顿的一间公寓。ERIN CLARK/GLOBE STAF

附原英文报道:

Boston Public Schools student homelessness hits all-time high

By Christopher Huffaker Globe Staff,Updated June 17, 2024

The paint on the walls was dirty and peeling and the windows looked out onto Blue Hill Avenue, filling the room with sounds of fights on the streets, vehicles whizzing past, and people talking and yelling.

Jaylene Macedo, then 6, couldn’t focus amid the chaos. The first-grader shared one cramped room with two beds in the Roxbury homeless shelter with her mom, Natalia Macedo, and younger sister, Ava.

She didn’t feel safe, often climbing into her mother’s bed until she fell asleep. For months, she kept asking her mother, “When are we going to have our own house?” or “When do I get my room back?”

Jaylene is one of more than 5,000 students in Boston Public Schools — more than 10 percent of the district’s population — who have experienced homelessness at some point this school year. It’s a record level for the district, a troubling trend that has been on the rise since the 2021-2022 school year. Across the country, students who are without permanent housing — whether in a shelter like the Macedos, on the street, or couch-surfing with family or friends — often suffer stark outcomes.

Data show they perform dramatically worse than their peers on state tests and graduate on time less frequently. Statewide, around one in five homeless students drops out of high school.

Why has it gotten so bad?

“A perfect storm,” said Brandy Brooks, head of the nonprofit Higher Ground, which works with BPS on housing efforts and helped house the Macedos.

Rents have hit record prices, higher than most places in the country. The eviction moratorium in place during the height of the pandemic has expired, pushing out many who had fallen behind on rent. An influx of migrants, many of them unaccompanied young people who have also entered the school system, have filled the state’s emergency shelters. And until additional federal funds are allocated, the Boston Housing Authority has no more federal housing subsidies, known as Section 8 vouchers, available — just as district efforts to funnel them to homeless families were beginning to bear fruit.

Homelessness has long been a challenge for BPS, with more than 4,000 homeless students enrolled in most recent years. The district has long worked to meet some of those students’ needs, with an annual winter coat drive and food pantries.

But in the last decade, tackling student homelessness has become more of a focus, said Nina Gaeta, the homeless liaison at East Boston High, with efforts to help homeless families cover necessities like food, warm clothing, and toiletries but also to help house them.

One partnership, the Early Homelessness Intervention Program with Family Aid Boston, focuses on preventing families from becoming homeless by connecting them with organizations that can provide financial, legal, or even health assistance, among other services, and has helped over 900 families since 2022, according to Brian Marques, the head of the Department of Opportunity Youth, which is responsible for supporting homeless students.

But the district’s biggest success has been helping to house over 1,600 families since 2021, Marques said. The Boston Housing Authority has an agreement with the district to issue available housing vouchers to BPS families, while the district and partners like Family Aid Boston help families search for housing and can provide money to help pay for brokers’ fees and security deposits. The district has also used city-funded vouchers to house some families and is partnering with the Housing Authority to get families access to public housing units.

“The numbers would’ve been astronomical if we had not housed them,” said Marques.

Albin Casilla of Dorchester is one student who the district helped house. Casilla emigrated from the Dominican Republic in 2019, when he was 14. He, his mother, and his brother were staying with family — a half-dozen people sharing a one-bedroom apartment. (”Doubling up,” or sharing someone else’s home due to economic hardship, qualifies as homelessness under federal law.)

Some of the family slept in the living room, but Casilla, trying to avoid frequent arguments and yelling among family members, preferred the safety and privacy of a small closet. He had to curl into the fetal position to lie down and sleep, and to strain his eyes to study in the dim closet light. His back still hurts, he said, but it was better than dealing with the family conflicts.

Unlike many homeless students, Casilla never missed school, spending as little time as possible in the cramped apartment.

“It was a situation where I did want to go to school,” Casilla said. “But at the same time it was pretty difficult to focus when you have a situation going on at home.”

Embarrassed, Casilla didn’t want to tell anyone about his living situation, but when a school counselor heard about it, she helped his mother get a Section 8 voucher and an apartment in Dorchester. Casilla, who just finished his freshman year at UMass-Boston, lives there still.

Casilla appreciates the help he got from BPS, but wants the schools to do more to publicize the support that is available, so others learn about it sooner.

In the case of the Macedos, who were left homeless after Jaylene’s grandmother sold the house they lived in, Natalia determined to get her daughters a new place as soon as possible and went to Jaylene’s school to seek help.

“If I talk to the school, maybe they’re able to help me, especially because my daughter goes there,” Macedo thought. “Nobody wants to see a child living in the shelter or being homeless.”

The school’s family liaison, Francisca Guevara, sat down with Macedo and told her the family was going to get through it. They filled out an application together, and Macedo got connected with Higher Ground, which spent months working with her — helping her gather documents, connecting her with leads on housing, and ensuring all the paperwork was in good order. Guevara, meanwhile, helped the Macedos get all the support they needed from the school, be it clothing, cleaning supplies, or supportive words.

“I never knew BPS could be so helpful,” Macedo said. “She helped a lot of families.”

In March, shortly after Jaylene’s seventh birthday, Macedo got the call: After seven months of living in the shelter, they had a home, in subsidized housing in Brighton.

“My kids’ faces really made me so happy,” Macedo said.

Often, said Gaeta, the homeless liaison at East Boston High, that feeling seems out of reach. She can help students who moved to the United States unaccompanied apply for the housing that exists, but she can’t create new housing herself.

“It feels terrible,” Gaeta said. “You want to solve that problem for them. And you know you can’t.”

Still, Gaeta said, the schools do what they can to support needy families. After surveying homeless students about a decade ago, East Boston High opened a food pantry and a clothing closet, and made laundry equipment available to students. The school got microwaves so that students who are working and don’t have time to eat can have some extra hot meals. And it works, said Gaeta. Many of the homeless students at her school are living in Boston without any family and working to support themselves, but they still come to school.

“They show up tired, but they do come,” Gaeta said. “And they might miss, they might have an absentee problem, but they’re still coming to school. And they’re trying.”

State data show that homeless students have much worse outcomes than their peers. In most grades and subjects, homeless BPS students meet grade-level expectations on the state MCAS exam at half the rate of their peers. About one-third fail to graduate on time; some of those students go on to graduate after five or more years, but many drop out. Statewide, the gaps are even more extreme.

Jaylene and her sister recently were assigned to a new school, the Edison K-8, in their new neighborhood. They’re making the apartment their own, putting up decorations, buying a new couch, and getting a pet, a small red fish in a pink tank. Jaylene no longer is afraid to sleep in her bed.

Macedo said she wants her daughters to grow up normally, knowing she’s there for them, to be kind to others and to appreciate life, “because you can have everything, and lose it in a second.” She said she’s lucky to be in the position she’s now in.

For advocates like Brandy Brooks of Higher Ground, that’s the problem.

“How can we have it not just be luck?” she asked Macedo recently. “There are many other families like yours…. How do we make sure everybody gets that same luck?”