【中美创新时报2024 年 4 月 10 日编译讯】(记者温友平编译)波士顿大学正在进行的研究生工人罢工让人们关注学费如何减少。对此,《波士顿环球报》记者Diti Kohli、Aidan Ryan 和通讯员 Esha Walia 作了下述详细报道。

上个月,当波士顿大学的研究生工人罢工时,迈克尔·马洛尼(Michael Maloney)的女儿发现她的学术生活被打乱了。她的生物学和人类学课程的讨论部分(通常由研究生助教主持)被彻底取消,她的新生入门写作课程也是如此。在本学期的四门课程中,只有化学课程按计划进行。

这让马洛尼想知道波士顿大学 66,670 美元的本科生学费到底花多少钱,以及为什么那些真正教他女儿的人的工资这么低。(她获得了一项择优奖学金,金额不到年度费用的三分之一。)

“她的学费的哪一部分应该用来支付教室前面的人合理的工资?” 来自纽约长岛的公共关系专业人士马洛尼问道,“那么这些钱都去哪儿了呢?”

自 3 月 25 日至少 1000 名研究生工人在工会谈判中罢工以来,这个问题一直困扰着家长、教授和学生。

代表员工的服务业雇员国际工会表示,罢工扰乱了波士顿大学约一半的课程,迫使教授们采取各种变通办法。另一方面,波士顿大学的一位发言人表示,只有不到 1% 的大学班级没有开会,并且相对较少的分组讨论小组受到干扰。在各种建议中,一位院长建议教授们考虑使用人工智能来填补研究生工作的空缺。

一直以来,波士顿大学都加入了越来越多昂贵的私立新英格兰学校行列。管理人员上个月宣布,下学年的总就读费用将超过 90,000 美元。

相比之下,波士顿大学研究生助理每周工作 20 小时的年薪通常为 27,000 美元至 40,000 美元,远低于大波士顿地区家庭收入中位数 103,000 美元。兼职人员面临着同样的经历:工资过低、工作过度、缺乏稳定性或确定性。

这归结于高等教育复杂的经济学——从劳动力到设施的一切成本导致学费不断上涨,但资金并不总是按预期流入教室。

是的,家庭支付给波士顿大学的一些学费已经被用于新建筑和华丽的设施,包括维护校园健身中心的漂流河,以及最近建造的查尔斯河旁闪闪发光的“Jenga”式数据科学大楼。(仅地热供暖和制冷系统就耗资 3.05 亿美元。)

但高等教育金融专家更多地指出了劳动力成本飙升、通货膨胀和入学人数波动的变化。他们说,深入挖掘就会发现,大学学费过高实际上是一个更广泛的经济趋势的症状:收入不平等。

非营利教育组织 Ithaka S&R 董事总经理、瓦萨学院前院长凯瑟琳·希尔 (Catharine Hill) 表示,学校尽可能提高学费标价,希望富裕家庭和许多国际学生能够支付全额运费。按照这样的价格,学生及其家人对设施和教育都有一定的期望。

“大学正在争夺有才华的高收入学生,他们想要一些他们付费的东西,”希尔说。 “每当大学的标价达到 10 倍时——50,000 美元、70,000 美元,现在是 90,000 美元——就会引发一场关于正在发生的事情的大讨论。”

那些全额支付运费的学生帮助学校支付账单,这些账单在通货膨胀率高达 8% 至 9% 的大流行时期攀升。较大的大学有时可以依靠他们的捐赠。但就像家庭食品、电力和日常用品的成本上涨一样,联邦大道沿线拥有 38,000 名学生的校园的成本也上涨了。学校正在进行或最近完成的 14 个建设项目——从学生会的新洒水装置到遍布校园的太阳能电池板——也没有变得更便宜。

总体而言,根据公开的税务文件,BU 的年度开支增长了 38%,从 2017 年的 20.6 亿美元增长到 2022 年的 28.4 亿美元——这一速度与同类学校保持一致。

学生实际支付的学费往往没有公众想象的那么快,尤其是对于中低收入家庭来说。

根据国家教育统计中心的趋势数据,2017 年私立高等教育的平均学费为 25,935 美元,2022 年将升至 26,998 美元,增幅为 4%。但考虑到通货膨胀,学费实际上下降了 300 美元。 (这些指标不包括食宿费用,例如在 BU,每年的费用高达 20,000 美元。)

根据经济援助专家马克·坎特罗维茨的研究,如今私立大学中只有四分之一的学生支付全价。 在公立机构——这些机构的学费通常较低,尤其是对于本州学生而言——这一数字约为 40%。 即使是高收入学校也为更多的学生提供经济援助。

波士顿大学的“净价”——学生在扣除奖学金和助学金后支付的费用——从 2020 年的 29,154 美元下降到 2022 年的 27,829 美元,甚至在考虑通货膨胀之前也是如此。根据教育部提供的数据机构显示,塔夫茨大学、韦尔斯利学院和波士顿学院的净价也保持不变或下降。

高等教育咨询公司 RPK 的高级合伙人唐娜·德罗彻斯 (Donna Desrochers) 表示,当然,经济援助已成为学校竞相吸引录取学生的一种方式,它们会在标价的基础上提供相当大的折扣,以吸引他们特别想要的录取学生。

“根据经济需要或其他属性向学生提供折扣本质上是对入学的激励,”她说。 “它现在已成为机构预算对话的一部分。”

另一个巨大的难题是:劳动力。

根据美国大学教授协会 2023 年的一份报告,自 1987 年以来,全国学术队伍已从大部分是终身教授和终身教授,转变为包括许多非终身教授、兼职教授和研究生。从理论上讲,这应该会降低成本,因为终身教授享有最高的工资和开展研究的灵活性。 但专家表示,薪酬仍占大多数机构资产负债表的 40% 至 70%。

为什么? 许多大学的非教学人员队伍不断壮大。《社会经济评论》的一项研究显示,1976 年至 2018 年间,美国大学全职管理人员的数量增长了 164%。 对于非教学专业人士(从招生人员到学术顾问的所有人)来说,这个数字增长了近五倍。

造成这种情况的原因有很多,其中一些与学校为学生提供的服务范围的扩大直接相关。 许多机构扩大了心理健康资源和辅导选择,以应对 COVID-19 后不断出现的健康问题和教育差异。

但这让许多现场讲师询问他们在财务状况中的位置。

在纠察线上,波士顿大学的毕业生们讲述了自己无力支付房租和水电费,依靠食品券生存,并且由于工资微薄而放弃购买食品杂货的情况。 据工会称,到 2023 年,波士顿大学 4,366 名毕业生中,只有 15 人的兼职收入超过 50,000 美元。

劳雷尔·奥伯施塔特-佩特里克 (Laurel Oberstadt-Petrik) 是一名神学硕士生,她正在努力承担适度上涨的租金。

“薪酬对我来说真的很重要,”奥伯施塔特-佩特里克说。 “我的房租每月上涨 110 美元,坦白说,这不是我能承受的。”

兼职教授和其他非终身教授的薪酬也成为一个痛处。

布里奇沃特州立大学 (Bridgewater State University) 的兼职教师布莱恩·N·杜查尼 (Brian N. Duchaney) 从 2007 年开始在多个国家支持的机构任教。但这些职位很少带来福利,而且杜查尼的津贴在过去 15 年里只增加了约 1,000 美元,从约 3,800 美元增加到 一个学期的课程费用为 5,200 美元。 他勉强凑够了钱,但这是一场持续不断的斗争。

与此同时,尽管波士顿大学等成本较高的私立学校在经历了短暂的疫情下滑后,入学率基本上出现了反弹,但许多公立大学由于申请者缺乏和出生率下降而面临着更大幅度的下降。 尽管如此,每个学生的成本仍在不断上升。

美国受托人和校友理事会的全国数据发现,在马萨诸塞州的公立机构,每个学生的教学费用从 2019 年的 17,454 美元上升到 2022 年的 18,459 美元(根据通货膨胀调整)。

“学生们对为什么学校每年的费用为 78,000 美元感到沮丧,”在布里奇沃特州立大学和巴布森学院任教的另一位兼职教师道格拉斯·布劳特 (Douglas Breault) 说。 “他们想要一张收据。”

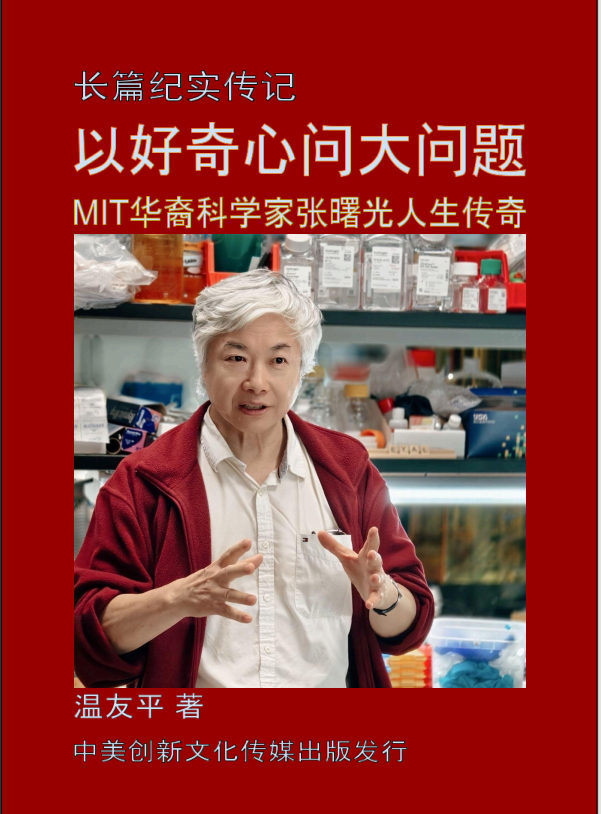

图片:波士顿大学研究生和支持者在波士顿大学的马什教堂周围游行。波士顿大学的研究生工人上个月举行罢工,寻求更好的工资和福利。 杰西卡·里纳尔迪/GLOBE 工作人员

题图:波士顿大学研究生在三月下旬举行罢工,要求公平工资、更好的医疗保险和更强的福利。JESSICA RINALDI/GLOBE STAFF

附原英文报道:

Undergraduate tuition at BU tops $66,000. Where does all the money go?

The ongoing graduate workers’ strike at Boston University has shone a spotlight on how tuition dollars trickle down

By Diti Kohli, Aidan Ryan and Esha Walia Globe Staff and Globe Correspondent,Updated April 10, 2024

When graduate student workers at Boston University walked off the job last month, Michael Maloney’s daughter saw her academic life interrupted. Her discussion sections for biology and anthropology courses, typically run by graduate teaching assistants, were canceled outright, as was her freshman introductory writing course. Of her four courses this semester, only chemistry is running as planned.

It makes Maloney wonder what BU’s $66,670 undergraduate tuition actually pays for, and why those who actually teach his daughter are paid so little. (She receives a merit-based scholarship that covers less than one-third of the annual cost.)

“What portion of her tuition should be going toward paying people at the front of the classroom a fair wage?” asked Maloney, a public relations professional from Long Island, N.Y. “And where is that money going instead?”

It’s a question that has been nagging parents, professors, and students themselves since at least 1,000 graduate workers went on strike amid union negotiations on March 25.

The Service Employees International Union that represents the employees said the strike has disrupted about half of BU classes, forcing professors into a wide range of workarounds. A spokesperson for BU, on the other hand, said that less than 1 percent of university classes are not meeting and a relatively small number of breakout discussion groups have been disrupted. One dean suggested — among various recommendations — that professors consider the use of artificial intelligence to fill in for grad student workers.

All the while, BU has joined a growing cohort of pricey, private New England schools. Administrators announced last month the total cost of attendance will top $90,000 next school year.

By contrast, BU graduate assistants typically earn $27,000 to $40,000 annually for what is described as a 20-hour workweek, well below the $103,000 median household income in Greater Boston. Adjuncts grapple with the same experience: underpaid and overworked, with little stability or certainty.

It comes down to the complicated economics of higher education — where the cost of everything from labor to facilities drives tuition ever-upward, but the money does not always flow into classrooms as expected.

Yes, some of the tuition money families pay to BU has found its way to new buildings and flashy amenities, including maintenance of the lazy river at the campus fitness center and the recent construction of the “Jenga”-style data science building that glimmers over the Charles River. (Its geothermal heating and cooling system cost $305 million alone.)

But higher education finance experts point more to the soaring cost of labor, inflation, and volatile changes in enrollment. Dig deeper, they say, and the exorbitant price of college is really a symptom of a broader trend in the economy: income inequality.

Catharine Hill, managing director of education nonprofit organization Ithaka S&R and former president of Vassar College, said schools raise the sticker price of tuition as high as they can in the hopes that wealthy families and many international students will pay full freight. At those prices, students and their families have certain expectations in terms of both facilities and education.

“Colleges are competing for talented high-income students, and they want some of those things that they pay for,” Hill said. “Every time the sticker price for college hits multiples of 10s — $50,000, $70,000, now $90,000 — there’s this big discussion of what is going on.”

And those full-freight-paying students help schools pay the bills, which climbed in the pandemic-era years of 8 to 9 percent inflation. Larger universities can sometimes lean on their endowment. But just like costs for food, electricity, and everyday goods rose for households, they increased, too, for the 38,000-student campus along Commonwealth Avenue. The 14 construction projects the school has underway or recently finished — ranging from new sprinklers in the student union to solar panels all over campus — did not get cheaper, either.

In all, according to publicly available tax documents, the annual expenses at BU climbed 38 percent, from $2.06 billion in 2017 to $2.84 billion by 2022 — a pace in keeping with similar schools.

The tuition students actually pay is often not climbing as fast as the public perceives, especially for low- and middle-income families.

The average tuition price for private postsecondary education sat at $25,935 in 2017, before rising to $26,998 in 2022 — a 4 percent increase — according to trend data from the National Center for Education Statistics. But account for inflation, and tuition actually fell $300 in that time. (These metrics do not include the cost of room, board, and fees, which, at BU for instance, tops $20,000 a year.)

Only one-quarter of students at private universities today shell out full price, according to research from financial aid expert Mark Kantrowitz. At public institutions — which typically have lower tuition, especially for in-state students — that number is about 40 percent. Even high-dollar schools are offering more students financial aid.

The “net price” at BU — what students pay after subtracting scholarships and grants — declined from $29,154 in 2020 to $27,829 in 2022, even before taking inflation into account. Net price has also remained static or gone down at Tufts University, Wellesley College, and Boston College, according to data institutions provided to the Department of Education.

Financial aid, of course, has become one way that schools compete to attract admitted students, offering a sizable discount from their sticker price to lure admitted students they particularly want, said Donna Desrochers, a senior associate at the higher education consulting firm RPK.

“Offering student discounts based on financial need or other attributes is inherently an incentive to attend,” she said. “It’s now part of institutions’ budget conversations.”

Another huge piece of the puzzle: labor.

Since 1987, the academic workforce nationwide has shifted from mostly tenured and tenure-track faculty to include many nontenure-track professors, adjuncts, and graduate workers, according to a 2023 report from the American Association of University Professors. In theory, that should drive down costs, since tenured faculty enjoy the highest wages and flexibility to conduct research. But compensation still comprises between 40 and 70 percent of most institutions’ balance sheets, experts said.

Why? The swelling ranks of nonteaching employees at many universities. Between 1976 and 2018, the number of full-time administrators at US colleges has grown 164 percent, according to a study in the Review for Social Economy. For nonteaching professionals (everyone from admissions staff to academic counselors), the number has grown nearly fivefold.

There are a host of reasons for this — some of which relate directly to the widening array of services schools provide students. Many institutions expanded their mental health resources and tutoring options in response to mushrooming health concerns and educational discrepancies in the wake of COVID-19.

But that has left many instructors on the ground asking where they fit into the financial picture.

At the picket line, BU graduate workers recount being unable to afford rent and utilities, surviving on food stamps, and forgoing groceries because of meager wages. In 2023, only 15 of BU’s 4,366 graduate workers earned more than $50,000 for part-time work, according to the union.

Laurel Oberstadt-Petrik, a master’s student in theology, is struggling to afford a modest rent increase.

“Pay really hits close to home for me,” Oberstadt-Petrik said. “My rent is going up $110 a month, which is not something that I can afford, frankly.”

Pay for adjunct and other nontenure-track professors has also emerged as a sore spot.

Brian N. Duchaney, an adjunct at Bridgewater State University, began teaching at multiple state-supported institutions in 2007. But the positions rarely come with benefits, and Duchaney’s stipend has increased by only around $1,000 in the past 15 years, from around $3,800 to $5,200 for a semester-long course. He scrapes together enough to get by, but it’s a constant struggle.

Meanwhile, though higher-cost private schools such as BU have largely seen enrollment rebound after a brief pandemic dip, many public colleges are bracing for bigger declines due to a lack of applicants and declining birth rates. Still, their costs per student keep going up.

National data from the American Council of Trustees and Alumni found that at public institutions in Massachusetts, instructional costs for each student rose from $17,454 in 2019 to $18,459 in 2022 — adjusted for inflation.

“Students are frustrated as to why school costs $78,000 a year,” said Douglas Breault, another adjunct who teaches at both Bridgewater State and Babson College. “They want a receipt.”

Boston University graduate worker students and supporters marched around BU’s Marsh Chapel. BU’s graduate worker students went out on strike last month seeking better pay and benefits. JESSICA RINALDI/GLOBE STAFF