“永不停歇”:波士顿大学罢工的研究生努力平衡教学、学习和生活

【中美创新时报2024 年 4 月 8 日编译讯】(记者温友平编译)从某些方面来说,波士顿大学的研究生是典型的大学生。他们没有多少钱。他们试图弄清楚自己的生活该怎么办。他们往往熬夜学习,也许还会点一两块披萨。但自3月下旬以来一直罢工的BU研究生也是大学员工,这不仅增加了他们的工作量,也使他们与学校的关系变得复杂。除了修读课程和撰写论文外,这些学生(其中一些年龄较大且有孩子)还需要授课、为学生提供建议和进行研究。正如博士生劳伦·雷恩斯(Lauren Rains)所说,“同时无处不在”。《波士顿环球报》记者凯蒂·约翰逊(Katie Johnston)对此作了下述详细报道。

根据 2022 年的城市数据,波士顿总共拥有大约 66,000 名研究生。与任何工作一样,教学和研究可能是一项无情且吃力不讨好的任务。是的,BU 的毕业生可以享受免费学费和 8 至 12 个月的津贴,起价分别为 26,000 美元和 39,000 美元,每周工作时间为 20 小时。但几乎没有护栏。作为SEIU Local 509的一部分,他们开始为第一份工会合同进行谈判,争取更高的工资和更好的福利,八个月后,他们就辞职了。

主要高等教育工会美国教师联合会主席兰迪·温加滕 (Randi Weingarten) 表示,全国各地的毕业生工人“完全受到剥削”。

马萨诸塞大学阿默斯特分校的社会学和劳动研究教授塞德里克·德莱昂说,教职员工会利用研究生,甚至让他们跑腿办事。“取他们的干洗衣服——这就是最终发生的事情,”他说,指的是他在密歇根读研究生期间发生的一起事件。

由于学生非常依赖教师作为顾问,因此抵制可能是有害的。“如果你敢于发声,你可能会将你的学术生涯和生计置于危险之中,”他说。

萨拉·拉迪诺·卡诺 (Sara Ladino Cano) 是哥伦比亚大学四年级博士生,研究哥伦比亚文学中的暴力行为,她对自己的职责感到不知所措,以至于她开始去看治疗师,甚至依靠他来帮助她处理财务问题,而她“没有这些” 时间或精神稳定”来自己做。但除了每周教授三节 50 分钟的西班牙语课程外,她无法跟上学业,因此决定退出该项目。

“这是不间断的,”28 岁的拉迪诺·卡诺 (Ladino Cano) 说。

波士顿大学发言人在一份声明中表示,学校将继续通过集体谈判来满足研究生的需求。“我们重视我们的研究生以及他们对教学和研究的许多贡献,”她说。

今年秋天,波士顿大学是众多当地院校之一,每年的学费、住宿费和其他费用将达到 9 万美元。

对于研究生来说,适应波士顿高昂的生活成本是一项重大斗争,他们通常不被允许从事外面的工作,尽管有些人悄悄地找到了其他工作或为教授做保姆。波士顿大学已开始扣留罢工研究生的工资,学生们正在努力安排互助捐款并计划聚餐,并将获得工会罢工资金。一些人表示,信用卡也可能会受到考验。

即使他们获得报酬,研究生工作者的预算限制也很大。

社会文化人类学六年级博士生汉娜·格蕾丝·霍华德 (Hannah Grace Howard) 在 Excel 电子表格上跟踪她的开支,该电子表格每月提醒她,她 26,000 美元的津贴中有 60% 被租金耗尽了。当杂货价格飙升时,她停止购买肉类——尽管她偶尔会花很多钱购买一包 3.99 美元的 Trader Joe’s 芒果干。当她的狗需要治疗耳朵感染的药物时,她不再点咖啡和外出就餐。

227 美元的眼科医生预约账单让她高枕无忧。“我在回家的火车上哭了,”29 岁的霍华德说。

练习瑜伽有助于缓解她撰写关于雅典希腊东正教教堂慈善捐赠的论文的压力,以及作为助教每周工作 30 个小时以上的压力。为了避免 20 美元的费用,她在每节课前后都在瑜伽馆做志愿者。

雷恩斯是历史系研究生,在路易斯安那州的一个低收入单亲家庭长大,没有得到家人的经济支持。为了延长 28,000 美元的津贴,她试图申请食品券,但发现自己不符合资格,于是申请了 4,000 美元的贷款,使她的学生债务增加到 30,000 美元。

23 岁的雷恩斯研究德国在非洲的殖民统治,每周花 16 个小时在课堂上,另外还要花 20 个小时写作,并认真阅读她每周分配阅读的 1000 页书,其中一些是德文的。上学期,雷恩斯担任每周两次、每次 90 分钟的纳粹本科生课程的助教,她每周独自教授两个小时的讨论部分,为 45 名学生制定课程计划、评分和主持办公时间。

她说,所有这一切对于毕业后就业市场来说“几乎不存在”。

麻省大学阿默斯特分校的德莱昂说,多年来,研究生工作者承担了以前由教职员工承担的课堂职责。与此同时,他说,更多的资金被投入到校园内创造“乡村俱乐部环境”,而不是投入到履行大学教育使命的人们身上。

“大学因为变得更加公司化,变得越来越依赖廉价劳动力,”他说。

谢林·德尔瓦莱·庞塞·德·莱昂(Cheyleann Del Valle Ponce de Leon )敏锐地感受到了这一点。由于每年租金将上涨 3,600 美元,这名药理学博士生将搬出位于芬威球场的 BU 研究生宿舍。她的津贴预计只会增加该数额的三分之一。

27 岁的德尔·瓦莱·庞塞·德莱昂 (Del Valle Ponce de Leon) 曾在波多黎各当过护士,现在一直在精打细算地筹集保证金以及第一个月和最后一个月的租金。午夜在实验室完成最近的一项实验后,当 T 已经停止运行时,她决定步行回家,而不是花 35 或 40 美元乘坐 Uber。

除了看电视和在沙发上编织之外,做任何有趣的事情都围绕一个单一的主题:“如果上面有免费这个词,我就会做,”她说。

与其他研究人员一样,德尔瓦莱·庞塞·德莱昂将在罢工期间继续为她的学位做实验室工作,但计划减少不属于她口腔癌研究一部分的行政任务和研讨会。

有孩子的研究生还有更多的事情要做。目前,符合条件的家庭有资格获得每年 600 美元的儿童保育津贴,这将支付大约一周的校内儿童保育费用。对于需要健康保险的父母来说,升级到家庭计划每年需要额外花费超过 1,100 美元,另外每个受抚养人还要花费 4,400 美元。

埃里克·蒙森 (Eric Munson) 是一名三年级计算机科学博士生,他是三个学龄儿童的离婚父亲,这些孩子都参加了母亲的保险,这些费用让家长们更难进入波士顿大学。

43 岁的蒙森(Munson )全职从事研究工作,每周工作 60 小时,年薪 43,000 美元。他说,与孩子们(年龄分别为 6 岁、9 岁和 13 岁)共度时光“需要相当严格的日程安排”,并且在他们上床睡觉后深夜继续工作。

他笑着说,他的目标是在 13 岁的女儿高中毕业之前获得学位。

“我不想和我的孩子一起上大学。”

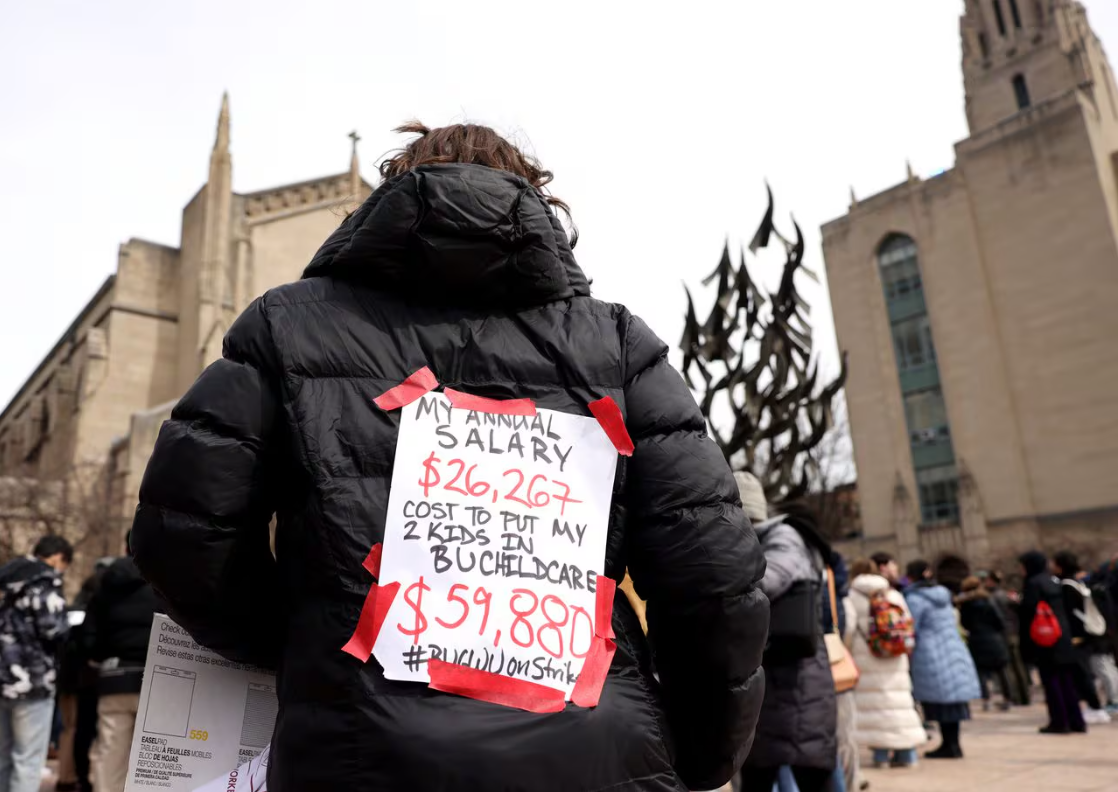

图片;3 月 25 日,罢工的波士顿大学研究生工人和支持者在波士顿大学马什教堂周围游行。JESSICA RINALDI/GLOBE STAFF

题图:波士顿大学的一名研究生在最近的一次集会上在她的背上贴了一条信息,指出迫使研究生工人罢工的差异。 JESSICA RINALDI/GLOBE STAFF

附原英文报道:

‘It’s nonstop’: Striking BU grad workers struggle to balance teaching, studying, life

By Katie Johnston Globe Staff,Updated April 8, 2024

In some ways, Boston University graduate students are typical college students. They don’t have much money. They’re trying to figure out what to do with their lives. And they tend to stay up late studying, and maybe ordering a pizza or two.

But the BU grad students, who have been on strike since late March, are also university employees, which not only adds to their workload but complicates their relationship with the school. In addition to taking courses and writing dissertations, the students — some of whom are older and have children — are expected to teach classes, advise students, and conduct research. “To be everywhere all at once,” as PhD student Lauren Rains put it.

In all, Boston is home to roughly 66,000 graduate students, according to 2022 city data. And as with any job, teaching and conducting research can be a relentless, thankless task. Yes, the BU grad workers are getting free tuition and eight-to-12-month stipends starting at $26,000 and $39,000, respectively, for what is supposed to be a 20-hour work week. But there are few guardrails in place. And eight months after they started bargaining for their first union contract as part of SEIU Local 509, pushing for higher wages and better benefits, they walked off the job.

Graduate workers around the country are “completely exploited,” said Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers, a major higher-education union.

Faculty members have been known to take advantage of grad students, even making them run personal errands, said Cedric de Leon, a sociology and labor studies professor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. “Picking up their dry cleaning — that’s what ends up happening,” he said, referring to an incident during his grad school days in Michigan.

And because students are so dependent on faculty members as advisers, pushing back can be detrimental. “By speaking up, you’re potentially putting your academic career and your livelihood in jeopardy,” he said.

Sara Ladino Cano, a fourth-year PhD student at BU from Colombia studying violence in Colombian literature, became so overwhelmed with her duties that she started seeing a therapist, even relying on him to help with her finances, which she “didn’t have time or mental stability” to do on her own. But she’s been unable to keep up with her studies, on top of teaching three 50-minute Spanish classes a week, and has decided to leave the program.

“It’s nonstop,” said Ladino Cano, 28.

In a statement, a BU spokesperson said the school would continue to address graduate students’ needs through collective bargaining. “We value our graduate students and their many contributions to teaching and research,” she said.

BU is among a number of local institutions where tuition, housing, and other expenses will hit $90,000 a year this fall.

Keeping up with the high cost of living in Boston is a major struggle for grad workers, who generally aren’t allowed to take outside jobs, although some quietly find other work or babysit for professors. BU has started withholding pay for striking grad workers, and students are working to arrange mutual aid donations and plan potlucks, and will have access to union strike funds. Credit cards may also get a workout, some said.

Even when they’re getting paid, the budget constraints of grad workers are significant.

Hannah Grace Howard, a sixth-year doctoral candidate in sociocultural anthropology, tracks her expenses on an Excel spreadsheet, which reminds her every month that 60 percent of her $26,000 stipend is eaten up by rent. When grocery prices surged, she stopped buying meat — though she occasionally splurges on a $3.99 package of Trader Joe’s dried mangos. When her dog needed medicine for an ear infection, she stopped ordering coffee and eating out.

A $227 bill for an eye doctor appointment put her over the top. “I cried on the train on the way home,” said Howard, 29.

Taking yoga helps manage the stress of writing her dissertation — on charitable giving in the Greek Orthodox church in Athens — and working upwards of 30 hours a week as a teaching fellow. To avoid the $20 cost, she volunteers at the yoga studio before and after each class.

Rains, the history grad worker, grew up in a low-income single-parent household in Louisiana, and doesn’t get financial support from her family. To stretch her $28,000 stipend, she tried to apply for food stamps, but found out she doesn’t qualify, and took out a $4,000 loan, boosting her student debt to $30,000.

Rains, 23, studies German colonization in Africa, and spends 16 hours a week in class and 20 more writing and plowing through the 1,000 pages she’s assigned to read each week, some of it in German. As a teaching fellow for a twice-a-week 90-minute undergrad class on Nazis last semester, Rains taught two hour-long discussion sections a week on her own, creating the lesson plans, grading, and holding office hours for 45 students.

All of this for a post-graduation job market that is “practically nonexistent,” she said.

Over the years, grad workers have taken on classroom duties previously handled by faculty members, said de Leon of UMass Amherst. At the same time, he said, more money is being devoted to creating “country club environments” on campus rather than to the people who fulfill the university’s educational mission.

“The university, because it’s becoming more corporatized, has become ever increasingly reliant on cheap labor,” he said.

Cheyleann Del Valle Ponce de Leon has felt that acutely. The second-year PhD student in pharmacology is moving out of BU graduate housing in the Fenway due to a $3,600 annual rent increase on the horizon. Her stipend is only expected to go up a third of that amount.

Del Valle Ponce de Leon, 27, who formerly worked as a nurse in Puerto Rico, has been pinching pennies to come up with a security deposit and first and last month’s rent. After finishing up a recent experiment at midnight in the lab, when the T had already stopped running, she decided to walk home instead of shelling out $35 or $40 for an Uber.

Doing anything fun outside of watching TV and crocheting on the couch revolves around a singular theme: “If it has the word free on it, I will do it, ” she said.

Like other researchers, Del Valle Ponce de Leon will continue doing lab work for her degree during the strike but plans to cut back on administrative tasks and seminars that aren’t part of her research on oral cancer.

Grad workers with children have even more on their plate. Currently, qualified families are eligible for a child-care stipend of $600 a year, which would pay for roughly a week of on-campus child care. For a parent in need of health insurance, upgrading to a family plan costs more than $1,100 extra a year, plus $4,400 for each dependent.

These costs make it much more difficult for parents to attend BU, said Eric Munson, a third-year computer science PhD student and a divorced father of three school-age children, who are on their mother’s insurance.

Munson, 43, earns $43,000 a year to conduct research full time, working up to 60 hours some weeks. Spending time with his kids, ages, 6, 9, and 13, “requires a fairly rigorous bit of scheduling,” he said — as well as resuming work late at night after they’re in bed.

His goal, he said with a laugh, is to get his degree before his 13-year-old daughter graduates from high school.

“I don’t want to be in college with my kid.”