【中美创新时报2024 年 3 月 26 日波士顿讯】(记者温友平编译)马萨诸塞州监察长办公室的一份报告称,该州创建了一个“存在严重缺陷”的系统,用于追踪公共退休人员在退休后工作中的收入是否超过应有水平,同时仍在领取养老金。《波士顿环球报》记者马特·斯托特(Matt Stout)对此作了下述详尽报道。

据州调查人员称,马萨诸塞州依靠“存在严重缺陷”的荣誉制度来确保返回公共部门的退休雇员遵守州对收入的限制,他们发现几乎没有监督,甚至计算了多少工资 退休人员可以做的事情异常复杂。

监察长杰弗里·S·夏皮罗 (Jeffrey S. Shapiro) 表示,没有一个中央机构来监督该州数十亿美元退休金系统中的退休人员是否遵守规定他们可以从公共机构赚取多少钱的法律,同时仍然领取纳税人资助的养老金。

相反,他的办公室在一份新报告中写道,这些规则主要是“通过自我监控的荣誉系统”来执行,该系统对该州大约 24 万名退休人员和受益人进行监督,其中数千人可以随时从事兼职公共工作 ——范围可以从“弱”到无效到“不存在”。

追踪退休人员收入的官员随后面临着一个错综复杂的过程,其中不同退休人员的收入上限可能会有很大波动。夏皮罗办公室表示,即使官员发现有人滥用规则,违规者除了偿还超额收入外,不会受到任何处罚。

“这太令人震惊了。我们在这方面做的工作越多,就越令人不安。”夏皮罗在接受采访时说道。 “对我来说,问题在于一家价值十亿美元的企业依赖退休人员在家里厨房餐桌上的餐巾纸上进行计算。”

根据州法律,那些刚刚从州或市政工作岗位退休的人如果重返马萨诸塞州的公共劳动力市场,将面临两套限制:他们一年的工作时间不能超过1200小时,而且只能赚取养老金与原工作人员当前工资之间的差额。

例如,如果退休人员现在的工资为 80,000 美元,而退休人员每年领取 50,000 美元养老金,那么他们退休后新的兼职公共工作的收入上限为 30,000 美元。退休一整年后,退休人员可以额外赚取 15,000 美元。

这些限制旨在阻止所谓的双重提款,并防止退休人员拿回比继续从事原来工作更多的纳税人资金。

对于较小的机构和市政当局来说,重新雇用退休人员通常比雇用年轻的全职员工更便宜。地方官员还辩称,他们在预算紧张的情况下寻求填补的一些高技术职位往往无法吸引很多合格的候选人,这使得退休人员成为一个有吸引力的选择。

但夏皮罗的办公室发现,追踪不同退休人员的数据很复杂。例如,如果现在填补退休人员职位的人获得加薪,那么退休人员的工资上限就会上升。但如果国家批准对退休人员养老金的生活成本进行调整(就像大多数年来的做法一样),那么上限就可以降低。

此外,该州 104 个退休委员会中只有少数几个实际上要求退休人员报告他们是否在工作。这些委员会每年总共向公共退休人员及其遗属支付约 93 亿美元,平均养老金约为 41,000 美元。

据监察长称,还有其他并发症。有关退休人员收入的调查和争议通常需要数年时间才能解决,特别是如果诉诸法庭的话。

举个例子,州教师退休系统在 2009 年收到一条举报,称一名退休学校管理人员正在为一家公共教育合作机构工作,其收入超出了应允许的水平。最终判定他的收入超出了限额 815,747 美元,但此案拖延了十多年,直到他用尽行政上诉为止。

“[法律]的执行是被动的,主要针对最恶劣的案件。超过收入上限的处罚是微乎其微的,”夏皮罗在给州长莫拉·希利和州立法者的信中写道,该信附在报告中。 “对于英联邦的退休系统来说,情况不应该如此,因为它是一个价值数十亿美元的企业。”

鉴于该州的分散跟踪系统,要确定有多少退休人员的收入可能超过允许的水平,即使不是不可能,也是很困难的。但在分析了大约 17,000 名退休教师五年来领取养老金的数据后,夏皮罗的办公室表示,发现其中 259 人的收入似乎超出了个人上限。

另外,当马萨诸塞州教师退休系统在 2019 年和 2020 年对 25 名似乎退休后收入最高的退休人员展开调查时,至少有 13 人的收入超出了允许的上限,在某些情况下超出了数十万美元。 报告称,一名退休人员的工资“超额”超过 365,000 美元,她最终放弃了大约 20,000 美元的年度养老金,而不是被扣押。

教师退休系统执行主任埃里卡·格拉斯特(Erika Glaster)表示,她不知道退休人员有“任何广泛”的努力来规避收入限制。但她说,复杂的规则令人困惑,而且常常收入超出应有水平的退休人员甚至不知道自己超出了上限。

“现在的方式确实行不通,”格拉斯特说。 “这是法规中很难执行的一部分。”

夏皮罗的办公室正在推动立法者考虑变革,包括向公共雇员退休管理委员会(104个退休制度的国家监管机构)赋予更多权力和资金,或者建立一个新的执法机构来跟踪退休人员收入。 他的报告还建议公共实体制定措施来跟踪退休人员的收入上限并向国家报告该信息。

报告称,州政府还应该通过使用“计算出的退休平均工资”来简化退休人员上限的设定方式,而不是将其与一个人过去职称的工资挂钩,后者可能会根据机构的不同而波动。

该州财政部长办公室和州退休委员会发言人安德鲁·纳波利塔诺表示,官员支持监察长的建议,包括授权一个机构对退休后收入实施限制。

纳波利塔诺说,这份报告“表明确实缺乏监督。”

剑桥退休委员会主席弗兰克·墨菲 (Frank Murphy) 表示,鉴于监控退休人员收入的复杂性和“劳动密集型”程度,他认为没有一个机构可以处理这一问题。

墨菲说:“一旦你把追踪成千上万人的责任交给一个机构,它就根本不会发挥作用。”

公共雇员退休管理委员会执行主任比尔·基夫周二表示,该机构仍在审查监察长的报告,并愿意“参与立法机关可能进行的任何对话”。

立法机关是否会接受监察长的许多建议尚不清楚。近年来,立法者在很大程度上已采取放松而非收紧对该系统的规则的措施。

2020年,他们完全放弃了收入上限,允许州和地方官员招募退休工人来填补疫情期间的空缺职位。第二年,他们将退休人员的工作时间上限从每年 960 小时提高到 1,200 小时,允许超过 130,000 名退休的国家雇员和教师——加上数千名从市政府退休的人——相当于在公共实体每周平均工作 23 小时,同时继续赚取养老金。

希利提出了自己的提议,其中包括一项允许州或地方官员取消“合格申请人严重短缺”职位的退休人员收入上限。她还单独寻求让马萨诸塞州警察培训机构负责人的退休警察局长将他 15 万美元的年薪和市政养老金带回家。

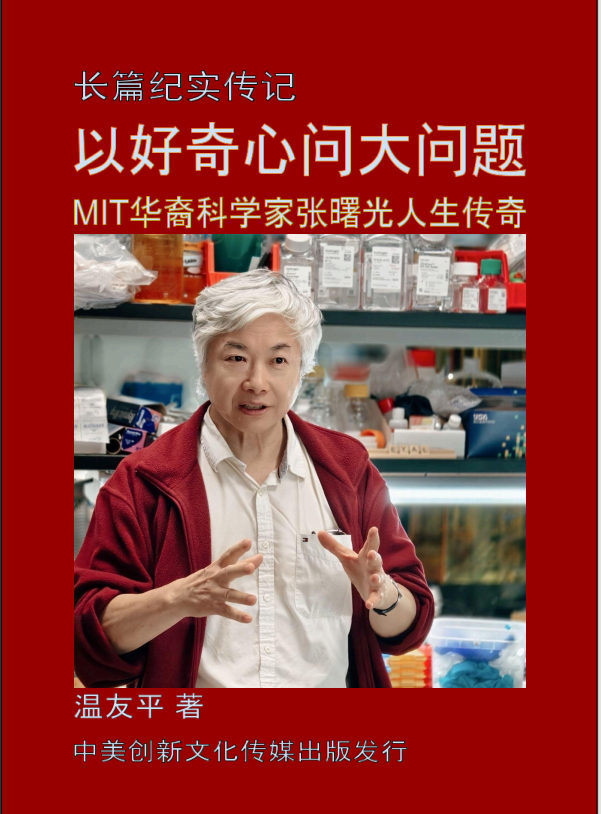

题图:马萨诸塞州监察长办公室的一份报告称,该州创建了一个“存在严重缺陷”的系统,用于追踪公共退休人员在退休后工作中的收入是否超过应有水平,同时仍在领取养老金。 DAVID L. RYAN/GLOBE STAFF

附原英文报道:

Mass. pays out billions in pensions. Oversight on how much retirees work can be ‘non-existent,’ investigators say.

By Matt Stout Globe Staff,Updated March 26, 2024

Massachusetts is relying on a “deeply flawed” honor system to ensure that retired employees who return to the public sector obey state limits on their earnings, according to state investigators, who found that there is little to no oversight and that even calculating how much a retiree can make is extraordinarily complicated.

Inspector General Jeffrey S. Shapiro said there’s no central agency that monitors whether retirees in the state’s multibillion-dollar retirement systems are abiding by laws that dictate how much they can earn from a public agency while still collecting their taxpayer-funded pension.

Instead, his office wrote in a new report, the rules are primarily enforced “through a self-monitored honor system,” where oversight of the state’s roughly 240,000 retirees and beneficiaries — thousands of whom can be working part-time public jobs at any time — can range from “weak” to ineffective to “non-existent.”

Officials who track what retirees earn are then faced with a Byzantine process, in which the caps on earnings can fluctuate wildly from retiree to retiree. Even when officials find that someone has abused the rules, violators face no penalties beyond having to pay back excess earnings, Shapiro’s office said.

“It was just shocking. The more work we did on this, the more troubling it was,” Shapiro said in an interview. “It’s problematic to me that a billion-dollar enterprise relies on retirees doing a calculation on a dinner napkin at home at their kitchen table.”

Under state law, those who are newly retired from a state or municipal job face two sets of limits if they return to the public workforce in Massachusetts: They can’t work more than 1,200 hours in a year, and they can only earn the difference between their pension and the current salary being paid to the person who now holds their old job.

For example, if the job the person retired from now pays an $80,000 salary, and the retiree is collecting a $50,000 annual pension, the income from their new part-time, post-retirement public job is capped at $30,000. After being retired for one full calendar year, the retiree can then earn an additional $15,000.

The limits are designed to stop so-called double dipping, and to prevent retirees from taking home more taxpayer dollars than if they had simply continued working in their original job.

For smaller agencies and municipalities, hiring back retirees is often a more inexpensive option than hiring a younger full-time employee. Local officials have also argued that some of the highly technical jobs they’re seeking to fill on tight budgets often don’t draw many qualified candidates, making a retiree an attractive choice.

But tracking the math from retiree to retiree is complicated, Shapiro’s office found. For example, should the person now filling a retiree’s job get a raise, then the retiree’s cap goes up. But if the state approves a cost-of-living adjustment for retirees’ pensions — as it does most years — the cap then can go down.

Further, only a handful of the state’s 104 retirement boards actually require retirees to report whether they are working. Collectively, thOse boards pay approximately $9.3 billion to public retirees and their survivors each year, with the average pension running about $41,000.

There are other complications, according to the inspector general. Investigations and disputes over a retiree’s earnings can often take years to resolve, particularly if they go to court.

In one example, the state teacher’s retirement system received a tip in 2009 that a retired school administrator was working for a public educational collaborative and making more than should be allowed. It ultimately determined he had made $815,747 above the limit, but the case dragged on for more than a decade until he exhausted his administrative appeals.

“Enforcement [of the law] is reactive, mostly directed at the most egregious cases. Penalties for exceeding the earnings cap are minimal,” Shapiro wrote in a letter to Governor Maura Healey and state lawmakers, which is attached to the report. “This should not be the case for the Commonwealth’s retirement system, which is a billion-dollar enterprise.”

Given the state’s decentralized tracking system, it’s difficult, if not impossible, to determine how many retirees could be earning more than they’re allowed. But after analyzing five years of data covering roughly 17,000 retired teachers who returned to work while collecting a pension, Shapiro’s office said it found that 259 appeared to be earning above their individual caps.

Separately, when the Massachusetts Teachers’ Retirement System launched investigations in 2019 and 2020 into 25 retirees who appeared to be earning the most post-retirement, at least 13 had made more than their cap allowed, in some cases by hundreds of thousands of dollars. One retiree, who was “overpaid” by more than $365,000, ultimately waived her roughly $20,000 annual pension rather than have it garnished, according to the report.

Erika Glaster, executive director of the teachers’ retirement system, said she’s not aware of “any widespread” efforts by retirees to skirt the earnings limits. But the complex rules are confusing and oftentimes retirees who earn more than they should aren’t even aware they exceeded their cap, she said.

”The way it is today really isn’t working,” Glaster said. “It’s a difficult piece of the statute to administer.”

Shapiro’s office is pushing lawmakers to consider changes, including giving more power and funding to the Public Employee Retirement Administration Commission, a state regulator of the 104 retirement systems, or creating a new enforcement agency to track retiree earnings. His report also recommends public entities be required to create measures to both track a retiree’s earnings cap and report that information to the state.

The state should also simplify how retirees’ caps are set by using a “calculated retirement salary average” instead of tying it to the salary of a person’s past job title, which can fluctuate depending on the agency, according to the report.

Andrew Napolitano, a spokesperson for the state treasurer’s office and state retirement board, said officials there support the inspector’s general’s recommendations, including to empower an agency to enforce limits on post-retiree earnings.

The report, Napolitano said, “demonstrates there is a real lack of oversight.”

Frank Murphy, chairman of the Cambridge Retirement Board, said that given how complex and “labor-intensive” it is to monitor retiree earnings, he doesn’t believe a single agency could handle it.

“Once you put the onus on one agency to track thousands and thousands of people, it’s not going to work well at all,” Murphy said.

Bill Keefe, executive director of the Public Employee Retirement Administration Commission, said Tuesday that the agency was still reviewing the inspector general’s report and is willing to “be a part of any conversations the Legislature may have.”

Whether the Legislature would embrace many of the inspector general’s recommendations is unclear. In recent years, lawmakers have largely moved to loosen — not tighten — the rules on the system.

In 2020, they waived the earnings cap entirely to allow state and local officials to recruit workers out of retirement to fill open positions amid the pandemic. The next year, they hiked the cap on retirees from 960 to 1,200 hours a year, allowing more than 130,000 retired state employees and teachers — plus thousands more who retired from municipal government — to work the equivalent of a 23-hour average workweek for a public entity while continuing to earn their pensions.

Healey has pushed her own proposals, including one to allow state or local officials to lift the cap on earnings for retirees for positions with a “critical shortage of qualified applicants.” She is separately seeking to allow the retired police chief who heads Massachusetts’ police training agency to take home both his $150,000-a-year salary and a municipal pension.