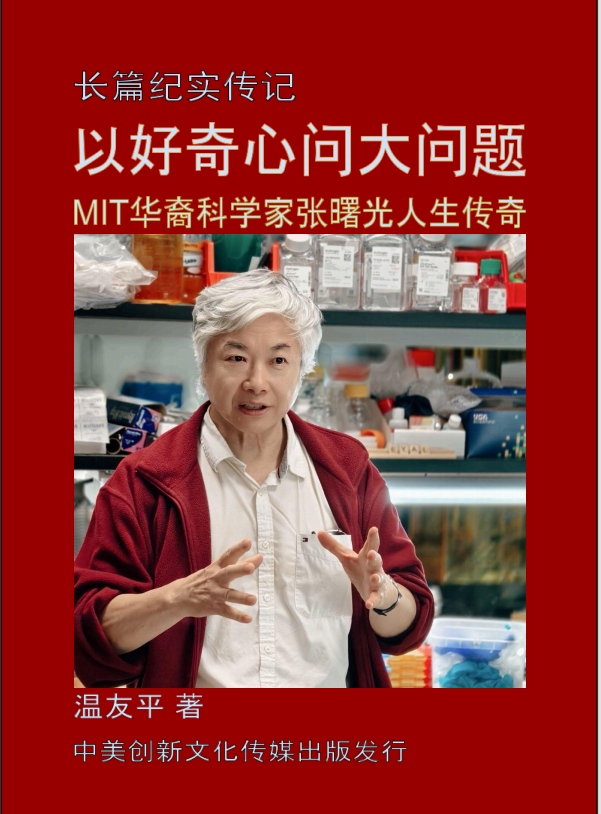

人工智能聊天机器人在诊断疾病方面击败了医生

【中美创新时报2024 年 11 月 22 日编译讯】(记者温友平编译)一项小型研究发现,在评估病史时,ChatGPT 的表现优于人类医生,即使那些医生正在使用聊天机器人。《纽约时报》记者Gina Kolata对此作了下述报道。

在一项实验中,使用 ChatGPT 诊断疾病的医生表现仅略好于未使用 ChatGPT 的医生。但仅凭聊天机器人,表现就胜过所有医生。

波士顿贝斯以色列女执事医疗中心的内科专家 Adam Rodman 博士满怀信心地预计,使用人工智能构建的聊天机器人将帮助医生诊断疾病。

他错了。

相反,在 Rodman 博士帮助设计的一项研究中,使用 ChatGPT-4 和常规资源的医生表现仅略好于无法使用该机器人的医生。令研究人员惊讶的是,ChatGPT 的表现竟然胜过医生。

“我很震惊,”罗德曼博士说。

OpenAI 公司的聊天机器人在根据病例报告诊断疾病并解释其原因时平均得分为 90%。随机分配使用聊天机器人的医生平均得分为 76%。那些随机分配不使用聊天机器人的医生平均得分为 74%。

这项研究不仅展示了聊天机器人的卓越表现。

它揭示了医生有时对自己做出的诊断坚定不移的信念,即使聊天机器人可能给出更好的诊断。

研究表明,虽然医生在工作中接触到了人工智能工具,但很少有人知道如何利用聊天机器人的能力。结果,他们未能利用人工智能系统解决复杂诊断问题并为他们的诊断提供解释的能力。

人工智能Rodman 博士说,系统应该是“医生的延伸者”,为诊断提供有价值的第二意见。

但似乎在实现这一潜力之前还有很长的路要走。

病例历史,病例未来

该实验涉及 50 名医生,包括通过几家大型美国医院系统招募的住院医生和主治医生,并于上个月在《JAMA Network Open》杂志上发表。

测试对象获得了六个病史,并根据他们提出诊断并解释为什么他们支持或排除这些诊断的能力进行评分。他们的成绩还包括最终诊断的正确性。

评分者是医学专家,他们只看到参与者的答案,而不知道这些答案是来自使用 ChatGPT 的医生、没有使用 ChatGPT 的医生还是来自 ChatGPT 本身。

研究中使用的病史基于真实患者,是研究人员自 1990 年代以来使用的 105 个病例的一部分。这些病例故意从未发表过,以便医学生和其他人可以在没有任何预知的情况下对其进行测试。这也意味着 ChatGPT 不可能接受过这些测试。

但是,为了说明研究内容,研究人员公布了医生接受测试的六个案例之一,以及一名得分高的医生和一名得分低的医生对该案例的测试问题的答案。

该测试案例涉及一名 76 岁的患者,他走路时腰部、臀部和小腿剧烈疼痛。疼痛开始于他接受球囊血管成形术以扩大冠状动脉几天后。手术后 48 小时内,他接受了血液稀释剂肝素治疗。

该男子抱怨自己发烧和疲倦。他的心脏病专家进行了实验室研究,表明他出现了新发贫血,血液中氮和其他肾脏废物堆积。该男子十年前曾因心脏病接受过搭桥手术。

案例小插图继续包括该男子体检的细节,然后提供了他的实验室测试结果。

正确的诊断是胆固醇栓塞——一种胆固醇碎片从动脉斑块中脱落并阻塞血管的疾病。

参与者被要求提供三种可能的诊断,每种诊断都有支持证据。他们还被要求针对每种可能的诊断提供不支持该诊断的结果或预期但未出现的发现。

参与者还被要求提供最终诊断。然后,他们要说出在诊断过程中将采取的最多三个额外步骤。

与已发表病例的诊断一样,研究中其他五个病例的诊断也不容易确定。但它们也并非罕见到几乎闻所未闻。然而,医生的平均表现比聊天机器人更差。

研究人员问道,到底发生了什么?

答案似乎取决于医生如何确定诊断,以及他们如何使用人工智能等工具。

机器中的医生

那么,医生如何诊断患者?

布莱根妇女医院医学史学家安德鲁·利博士表示,问题在于“我们真的不知道医生是如何思考的”。

利博士说,在描述他们如何得出诊断时,医生会说“直觉”或“根据我的经验”。

几十年来,这种模糊性一直困扰着研究人员,因为他们试图制作能够像医生一样思考的计算机程序。

这项探索始于近 70 年前。

“自从有了计算机,就有人试图用它们来做诊断,”Lea 博士说。

最雄心勃勃的尝试之一始于 20 世纪 70 年代的匹兹堡大学。那里的计算机科学家招募了医学院内科系主任 Jack Myers 博士,他被称为诊断大师。他记忆力超群,每周花 20 个小时待在医学图书馆,试图学习医学上已知的一切知识。

Myers 博士获得了病例的医疗细节,并在思考诊断时解释了他的推理。计算机科学家将他的逻辑链转换成代码。由此产生的程序称为 INTERNIST-1,包括 500 多种疾病和大约 3,500 种疾病症状。

为了测试它,研究人员提供了来自《新英格兰医学杂志》的病例。“计算机表现非常好,”Rodman 博士说。它的表现“可能比人类更好,”他补充道。

但 INTERNIST-1 从未起飞。它很难使用,需要一个多小时才能提供诊断所需的信息。而且,它的创建者指出,“目前程序的形式对于临床应用来说不够可靠。”

研究仍在继续。到 20 世纪 90 年代中期,大约有六个计算机程序试图做出医学诊断。没有一个得到广泛使用。

“这不仅要求它易于使用,而且医生必须信任它,”罗德曼博士说。

由于对医生如何思考存在不确定性,专家们开始问他们是否应该关心。尝试设计计算机程序以与人类相同的方式进行诊断有多重要?

“关于计算机程序应该在多大程度上模仿人类推理存在争议,”Lea 博士说。“我们为什么不发挥计算机的优势呢?”

计算机可能无法清楚地解释其决策路径,但如果它做出正确的诊断,这重要吗?

随着 ChatGPT 等大型语言模型的出现,对话发生了变化。它们并没有明确地试图复制医生的思维;它们的诊断能力来自于预测语言的能力。

“聊天界面是杀手级应用,”这项新研究的作者、斯坦福大学医生兼计算机科学家乔纳森·H·陈博士说。

“我们可以把整个病例输入计算机,”他说。“几年前,计算机还不懂语言。”

但许多医生可能没有挖掘它的潜力。

操作员错误

在对新研究的结果感到震惊之后,罗德曼博士决定更深入地探究数据,并查看医生和 ChatGPT 之间的实际消息日志。医生们一定看到了聊天机器人的诊断和推理,那么为什么那些使用聊天机器人的人没有做得更好呢?

事实证明,当聊天机器人指出与他们的诊断不一致的东西时,医生们往往不会被说服。相反,他们倾向于坚持自己对正确诊断的想法。

“他们不听人工智能的。”当人工智能告诉他们不同意的事情时,”罗德曼博士说。

这是有道理的,鹿特丹伊拉斯姆斯医学中心研究临床推理和诊断错误的劳拉·兹万说,她没有参与这项研究。

“当人们认为自己是对的时候,他们通常会过于自信,”她说。

但还有另一个问题:许多医生不知道如何充分利用聊天机器人。

陈博士说,他注意到,当他查看医生的聊天记录时,“他们把它当作一个搜索引擎,用于定向提问:‘肝硬化是癌症的风险因素吗?眼睛疼痛的可能诊断是什么?’”

“只有一小部分医生意识到,他们可以把整个病史复制粘贴到聊天机器人中,让它对整个问题给出全面的回答,”陈博士补充道。

“只有一小部分医生真正看到了聊天机器人能够给出令人惊讶的聪明而全面的答案。”

题图:从走廊看向医疗中心检查室的景色。图源Michelle Gustafson

附原英文报道:

A.I. Chatbots Defeated Doctors at Diagnosing Illness

A small study found ChatGPT outdid human physicians when assessing medical case histories, even when those doctors were using a chatbot.

A view from a hallway into an exam room of a health care center.

In an experiment, doctors who were given ChatGPT to diagnose illness did only slightly better than doctors who did not. But the chatbot alone outperformed all the doctors.Credit…Michelle Gustafson for The New York Times

By Gina Kolata Nov. 17, 2024

Dr. Adam Rodman, an expert in internal medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, confidently expected that chatbots built to use artificial intelligence would help doctors diagnose illnesses.

He was wrong.

Instead, in a study Dr. Rodman helped design, doctors who were given ChatGPT-4 along with conventional resources did only slightly better than doctors who did not have access to the bot. And, to the researchers’ surprise, ChatGPT alone outperformed the doctors.

“I was shocked,” Dr. Rodman said.

The chatbot, from the company OpenAI, scored an average of 90 percent when diagnosing a medical condition from a case report and explaining its reasoning. Doctors randomly assigned to use the chatbot got an average score of 76 percent. Those randomly assigned not to use it had an average score of 74 percent.

The study showed more than just the chatbot’s superior performance.

It unveiled doctors’ sometimes unwavering belief in a diagnosis they made, even when a chatbot potentially suggests a better one.

And the study illustrated that while doctors are being exposed to the tools of artificial intelligence for their work, few know how to exploit the abilities of chatbots. As a result, they failed to take advantage of A.I. systems’ ability to solve complex diagnostic problems and offer explanations for their diagnoses.

A.I. systems should be “doctor extenders,” Dr. Rodman said, offering valuable second opinions on diagnoses.

But it looks as if there is a way to go before that potential is realized.

Case History, Case Future

The experiment involved 50 doctors, a mix of residents and attending physicians recruited through a few large American hospital systems, and was published last month in the journal JAMA Network Open.

The test subjects were given six case histories and were graded on their ability to suggest diagnoses and explain why they favored or ruled them out. Their grades also included getting the final diagnosis right.

The graders were medical experts who saw only the participants’ answers, without knowing whether they were from a doctor with ChatGPT, a doctor without it or from ChatGPT by itself.

The case histories used in the study were based on real patients and are part of a set of 105 cases that has been used by researchers since the 1990s. The cases intentionally have never been published so that medical students and others could be tested on them without any foreknowledge. That also meant that ChatGPT could not have been trained on them.

But, to illustrate what the study involved, the investigators published one of the six cases the doctors were tested on, along with answers to the test questions on that case from a doctor who scored high and from one whose score was low.

That test case involved a 76-year-old patient with severe pain in his low back, buttocks and calves when he walked. The pain started a few days after he had been treated with balloon angioplasty to widen a coronary artery. He had been treated with the blood thinner heparin for 48 hours after the procedure.

The man complained that he felt feverish and tired. His cardiologist had done lab studies that indicated a new onset of anemia and a buildup of nitrogen and other kidney waste products in his blood. The man had had bypass surgery for heart disease a decade earlier.

The case vignette continued to include details of the man’s physical exam, and then provided his lab test results.

The correct diagnosis was cholesterol embolism — a condition in which shards of cholesterol break off from plaque in arteries and block blood vessels.

Participants were asked for three possible diagnoses, with supporting evidence for each. They also were asked to provide, for each possible diagnosis, findings that do not support it or that were expected but not present.

The participants also were asked to provide a final diagnosis. Then they were to name up to three additional steps they would take in their diagnostic process.

Like the diagnosis for the published case, the diagnoses for the other five cases in the study were not easy to figure out. But neither were they so rare as to be almost unheard-of. Yet the doctors on average did worse than the chatbot.

What, the researchers asked, was going on?

The answer seems to hinge on questions of how doctors settle on a diagnosis, and how they use a tool like artificial intelligence.

The Physician in the Machine

How, then, do doctors diagnose patients?

The problem, said Dr. Andrew Lea, a historian of medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital who was not involved with the study, is that “we really don’t know how doctors think.”

In describing how they came up with a diagnosis, doctors would say, “intuition,” or, “based on my experience,” Dr. Lea said.

That sort of vagueness has challenged researchers for decades as they tried to make computer programs that can think like a doctor.

The quest began almost 70 years ago.

“Ever since there were computers, there were people trying to use them to make diagnoses,” Dr. Lea said.

One of the most ambitious attempts began in the 1970s at the University of Pittsburgh. Computer scientists there recruited Dr. Jack Myers, chairman of the medical school’s department of internal medicine who was known as a master diagnostician. He had a photographic memory and spent 20 hours a week in the medical library, trying to learn everything that was known in medicine.

Dr. Myers was given medical details of cases and explained his reasoning as he pondered diagnoses. Computer scientists converted his logic chains into code. The resulting program, called INTERNIST-1, included over 500 diseases and about 3,500 symptoms of disease.

To test it, researchers gave it cases from the New England Journal of Medicine. “The computer did really well,” Dr. Rodman said. Its performance “was probably better than a human could do,” he added.

But INTERNIST-1 never took off. It was difficult to use, requiring more than an hour to give it the information needed to make a diagnosis. And, its creators noted, “the present form of the program is not sufficiently reliable for clinical applications.”

Research continued. By the mid-1990s there were about a half dozen computer programs that tried to make medical diagnoses. None came into widespread use.

“It’s not just that it has to be user friendly, but doctors had to trust it,” Dr. Rodman said.

And with the uncertainty about how doctors think, experts began to ask whether they should care. How important is it to try to design computer programs to make diagnoses the same way humans do?

“There were arguments over how much a computer program should mimic human reasoning,” Dr. Lea said. “Why don’t we play to the strength of the computer?”

The computer may not be able to give a clear explanation of its decision pathway, but does that matter if it gets the diagnosis right?

The conversation changed with the advent of large language models like ChatGPT. They make no explicit attempt to replicate a doctor’s thinking; their diagnostic abilities come from their ability to predict language.

“The chat interface is the killer app,” said Dr. Jonathan H. Chen, a physician and computer scientist at Stanford who was an author of the new study.

“We can pop a whole case into the computer,” he said. “Before a couple of years ago, computers did not understand language.”

But many doctors may not be exploiting its potential.

Operator Error

After his initial shock at the results of the new study, Dr. Rodman decided to probe a little deeper into the data and look at the actual logs of messages between the doctors and ChatGPT. The doctors must have seen the chatbot’s diagnoses and reasoning, so why didn’t those using the chatbot do better?

It turns out that the doctors often were not persuaded by the chatbot when it pointed out something that was at odds with their diagnoses. Instead, they tended to be wedded to their own idea of the correct diagnosis.

“They didn’t listen to A.I. when A.I. told them things they didn’t agree with,” Dr. Rodman said.

That makes sense, said Laura Zwaan, who studies clinical reasoning and diagnostic error at Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam and was not involved in the study.

“People generally are overconfident when they think they are right,” she said.

But there was another issue: Many of the doctors did not know how to use a chatbot to its fullest extent.

Dr. Chen said he noticed that when he peered into the doctors’ chat logs, “they were treating it like a search engine for directed questions: ‘Is cirrhosis a risk factor for cancer? What are possible diagnoses for eye pain?’”

“It was only a fraction of the doctors who realized they could literally copy-paste in the entire case history into the chatbot and just ask it to give a comprehensive answer to the entire question,” Dr. Chen added.

“Only a fraction of doctors actually saw the surprisingly smart and comprehensive answers the chatbot was capable of producing.”