共和党希望让特朗普减税政策永远持续下去

【中美创新时报2025 年 4 月 7日编译讯】(记者温友平编译)共和党过去减税时,只是暂时的,他们屈服于华盛顿神秘的预算规则,这些规则限制了他们可以增加联邦赤字的数额。他们赌一把——而且大部分都成功了——认为减税不会真正结束,因为民主党最终会投票继续减税。然而,随着今年的减税,许多共和党人不再愿意冒这个险。《纽约时报》记者安德鲁·杜伦对此作了下述报道。

在参议院,共和党于周六批准了一份预算大纲,这为在没有民主党支持的情况下无限期锁定特朗普减税政策打开了大门。

实际上,这样做需要共和党人颠覆长期以来限制议员按照党派路线行事的参议院程序。这将标志着保守机构发生重大变化,并促使民主党人在下次控制参议院时采取重大新举措。

参议院共和党人认为特朗普的减税措施是值得的。共和党于 2017 年首次通过了减税措施,降低了大多数人的个人所得税率,扩大了标准扣除额,并削减了企业税。

由于当时他们使用的是华盛顿的标准会计方法,许多减税措施将在今年年底到期。如果另一项法案得不到通过,立法者现在面临着财政悬崖,许多美国人的税收将会增加。

共和党人承认,减税政策到期后,他们很幸运能够控制国会和白宫。他们可以继续减税,而不必与民主党人谈判,因为民主党人一直试图取消部分减税政策。

但一些共和党人担心,他们可能不会再有这样的好运。民主党在未来的税收斗争中可能会拥有更大的权力。

“每当这种情况发生时,民主党人就会趁机说,‘好吧,除非你给我们这些支出或破坏性的税收政策,否则我们将扣留你 5 万亿美元的减税计划,’然后你就必须妥协,”美国税收改革组织主席格罗弗·诺奎斯特说。“每五年或十年消除一次财政悬崖是向前迈出的一大步。”

当然,没有哪项法律是永久的。立法者可以随时投票再次改变税收政策。但国会往往只有在面临最后期限时才会对棘手的财政问题采取行动。

这里解释了为什么减税政策通常会到期,以及共和党人希望如何使减税政策继续有效。

为什么减税通常是暂时的?

参议院的大多数立法都需要 60 票才能避免阻挠议事,这个门槛意味着即使是控制参议院的政党也不一定能通过它想要的政策。但有一个重要的例外:立法者只需简单多数即可通过一项名为预算协调的特殊程序通过财政政策。

参议院周六通过的预算决议是和解进程的早期阶段,众议院共和党人现在必须对参议院的计划发表意见,然后才能继续进行数月的实际立法谈判。

协调程序对立法者可以通过该程序通过的法案有诸多限制。长期以来,其最重要的规则之一就是,使用该程序通过的法案不能迫使政府在长期内借入更多资金。立法者可以通过协调程序通过政策,从而在十年内增加赤字,但此后,支出增加或减税的成本必须由其他储蓄来支付——在预期联邦收入减少数万亿美元的情况下,这是一项艰巨的任务。

民主党人曾表示,特朗普减税政策到期后,他们将继续保留大部分减税措施。在今年的辩论前,民主党领导人承诺不会对年收入低于 40 万美元的美国人加税,而进步派民主党人则推动对企业和富人加税。

共和党人不希望未来再经历两党谈判。他们还认为,即使特朗普总统的关税政策已经打乱了企业的投资计划,但永久实施减税措施仍有助于企业规划投资并刺激经济增长。

“参议院共和党人与总统一致认为,暂时延长税收期限是不可接受的,”参议院多数党领袖、南达科他州共和党参议员约翰·图恩 (John Thune) 表示。“美国人不应该每隔几年就生活在加税的恐惧之中。”

共和党如何能实现这一目标?

参议院共和党人计划改变会计准则,并表明无限期延长特朗普减税政策实际上不会在长期内增加赤字——因此在和解中是允许的。

这一策略取决于如何评估减税的成本。通常,续签即将到期的减税措施与通过新的减税措施的处理方式相同。根据这一被称为“现行法律基准”的指标,继续实施特朗普的减税措施将在未来十年花费约 3.8 万亿美元。

在参议院,共和党通过了一份预算大纲,其中采用了另一种方法:假设现行政策将继续下去,即使是暂时的。这一“现行政策基准”假设特朗普的减税措施不会给预算带来新的成本。

这一策略只是一种假象,表明特朗普的减税政策不会产生任何成本。但他们表示,参议院共和党人真正的动机是绕过和解对赤字的限制。参议院共和党人正准备援引多年前预算法案中的一项条款,该条款允许预算委员会主席、南卡罗来纳州共和党参议员林赛·格雷厄姆 (Lindsey Graham) 单方面决定某些政策的成本,而不是由无党派的计分员来决定。

特朗普减税政策的延续将使美国财政前景黯淡。无党派的统计机构国会预算办公室估计,如果特朗普减税政策在未来 30 年内持续下去,到 2054 年,美国的债务将比预期高出近 20%。

本文最初刊登于《纽约时报》。

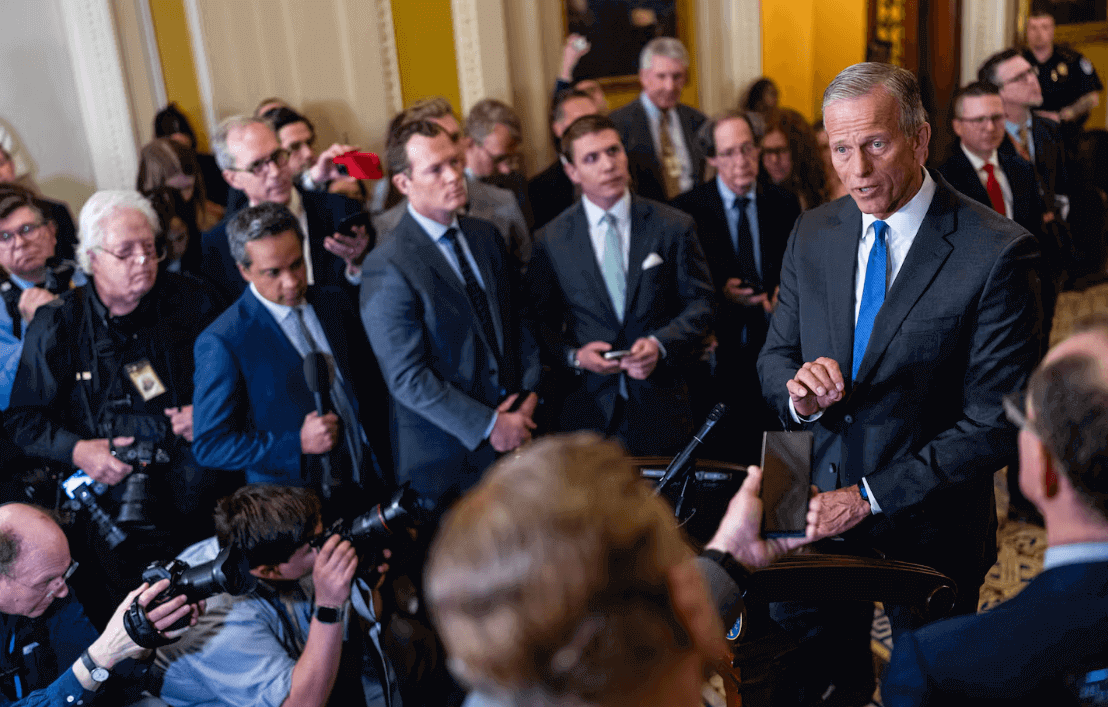

题图:南达科他州参议员、共和党多数党领袖约翰·图恩表示,“参议院共和党人与总统一致认为,暂时延长期限是不可接受的。” Eric Lee/NYT

附原英文报道:

Republicans want to make the Trump tax cuts last forever

By Andrew Duehren New York Times,Updated April 6, 2025

Senator John Thune of South Dakota, the Republican majority leader, said, “Senate Republicans are united with the president in viewing a temporary extension as unacceptable.”Eric Lee/NYT

WASHINGTON — When Republicans cut taxes in the past, they did so only temporarily, bowing to Washington’s arcane budget rules that limited how much they could add to the federal deficit. They gambled — mostly successfully — that the tax cuts would not actually end because Democrats would eventually vote to continue them.

With this year’s tax cut, though, many Republicans no longer want to take that risk.

In the Senate, Republicans approved a budget outline Saturday that opens the door to locking in the Trump tax cuts indefinitely without Democratic support.

Actually doing so would require Republicans to upend Senate procedures that have long governed what lawmakers can accomplish along party lines. That would mark a dramatic change in the hidebound institution and invite Democrats to take major new steps of their own when they next control the chamber.

Senate Republicans believe that the Trump tax cuts are worth it. The party first passed the cuts in 2017, lowering individual income rates for most people, expanding the standard deduction, and slashing corporate taxes.

Because they used standard Washington accounting methods at the time, many of the tax cuts are set to expire at the end of this year. Lawmakers are now facing a fiscal cliff that would increase taxes on many Americans if another bill isn’t passed.

Republicans acknowledge their good fortune in controlling Congress and the White House as the tax cuts come to an end. They can keep them going without having to negotiate with Democrats, who have sought to roll back some of the cuts.

But some Republicans worry that they may not get so lucky again. Democrats could have more power in future tax fights.

“Whenever that happens, the Democrats have a bite at the apple to say, ‘Well, we’ll hold your $5 trillion tax cut hostage unless you give us this spending or this destructive tax policy,’ and then you have to compromise,” said Grover Norquist, president of Americans for Tax Reform. “Ending that fiscal cliff every five or 10 years is a huge step forward.”

Of course, no law is necessarily permanent. Lawmakers could always vote to change tax policy again. But Congress only tends to act on thorny fiscal questions when it faces a deadline.

Here is an explanation of why tax cuts usually expire and how Republicans hope to make the cuts stay in place.

Why are tax cuts usually temporary?

Most legislation in the Senate requires 60 votes to avoid a filibuster, a threshold that means even the party that controls the chamber cannot always pass the policies it wants. But there is an important carve-out: Lawmakers only need a simple majority to pass fiscal policy through a special procedure called budget reconciliation.

Senate passage of a budget resolution Saturday was an early stage of the reconciliation process, and Republicans in the House now have to weigh in on the Senate plan before the party can move ahead with months of negotiations over the actual legislation.

Reconciliation includes a number of restrictions on what lawmakers can pass through the process. One of its most important rules has long been that bills using the procedure cannot force the government to borrow more money in the long term. Lawmakers can pass policies through reconciliation that add to the deficit over a decade, but after that the cost of a spending increase or tax cut has to be covered by other savings — a tall order when reducing expected federal revenue by trillions of dollars.

Democrats had suggested that they would keep much of the Trump tax cuts in place when they expired. Heading into this year’s debate, Democratic leaders pledged to not raise taxes on Americans making less than $400,000 each year, while progressive Democrats pushed to raise taxes on corporations and the rich.

Republicans do not want to go through a bipartisan negotiation in the future. They also believe that making the cuts permanent could help businesses plan their investments and spur economic growth, even though corporate planning has been thrown into disarray by President Trump’s tariffs.

“Senate Republicans are united with the president in viewing a temporary extension as unacceptable,” said Senator John Thune, Republican of South Dakota, the majority leader. “Americans should not have to live in fear of a tax hike every few years.”

How could Republicans pull this off?

Senate Republicans plan to change accounting standards and show that extending the Trump tax cuts indefinitely does not, in fact, add to the deficit in the long term — and therefore is allowed in reconciliation.

The strategy hinges on how the cost of tax cuts is assessed. Typically, renewing an expiring tax cut is treated the same way as passing a new tax cut. By that metric, called a “current law baseline,” continuing the Trump tax cuts would cost roughly $3.8 trillion over the next decade.

In the Senate, Republicans passed a budget outline that embraces a different method: assuming that the current policies will continue even if they are temporary. This “current policy baseline” assumes that the Trump tax cuts are not a new cost to the budget.

That strategy amounts to an illusion, showing that the Trump tax cuts do not cost anything. But the real motivation for Senate Republicans, they say, is to work around reconciliation’s restrictions on deficits. Senate Republicans are preparing to invoke a clause in years-old budget legislation that allows Senator Lindsey Graham, Republican of South Carolina, who heads the budget committee, to unilaterally decide what certain policies cost, instead of nonpartisan scorekeepers.

Keeping the Trump tax cuts in place would significantly darken the country’s fiscal outlook. The Congressional Budget Office, a nonpartisan scorekeeper, estimated that America’s debt in 2054 would be almost 20 percent larger than expected if the Trump tax cuts continued for the next 30 years.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.