谁才是 Uber 和 Lyft 真正的掌舵人?从很多方面来说都是人工智能

【中美创新时报2024 年 8 月 4 日编译讯】(记者温友平编译)最近对 Uber 和 Lyft 司机就业权利的审判揭示了人工智能如何指导他们的商业模式。审判证词揭示了这些公司算法的力量——并对其对劳动力的影响提出了质疑。《波士顿环球报》记者凯蒂·约翰斯顿(Katie Johnston)对此作了下述详细报道。

布兰迪斯大学教授兼劳动力市场专家大卫·韦尔(David Weil )知道 Uber 和 Lyft 长期以来一直使用算法来匹配司机的供应和乘客的需求,并据此设定价格。

但当他仔细研究最近马萨诸塞州针对叫车公司的诉讼中提供的证词、文件和数据时,他发现算法背后的人工智能远比他想象的要复杂得多。这些算法从数百万次行程中收集的大量数据中学习,可以预测乘客在特定情况下愿意支付多少费用,以及司机可能接受多少补偿。

例如,在凯尔特人队比赛结束后,前往韦斯顿的人可能会比前往弗雷明翰的人支付更高的费用,这是因为韦斯顿的乘客可能更富有,愿意支付更多费用以尽快回家,韦尔发现。比赛结束后的高需求也会促使算法提高工资,让更多的司机上路,但这并不是一个公平的竞争环境。

那些被认为高价值的司机可能会获得额外的激励来开车更多,而其他人可能会得到更少的机会。但客户和司机都没有完全意识到他们是如何或为什么受到不同的对待的。

韦尔的研究让我们看到了人工智能的力量及其重塑公司、工人和消费者之间关系的潜力。人工智能几乎可以立即筛选从应用程序、在线活动和销售点系统收集的大量数据,这可能会给公司带来巨大的优势。它将允许他们根据个人情况定制价格和薪酬,这意味着消费者和工人做出的每个决定最终都可能影响他们支付或获得多少报酬。

“人工智能和机器学习越来越多地使用非常非常细微的数据,令人不安的一件事是,你可以想办法诱骗人们,给他们支付的金额恰好是让他们工作所需的金额,”前劳工部工资和工时部门负责人韦尔说。“而且一分钱也不会多。”

对 Uber 和 Lyft 运营方式的洞察来自于在诉讼的调查阶段移交给州的材料,这些材料针对这两家公司将司机错误地归类为独立承包商而不是雇员。该案在结案辩论前一天得到解决,司机获得了新的福利,工资从每小时 32.50 美元起,并补发了工资,但并未解决司机的就业状况(雇员还是承包商?)或公司算法的透明度问题。

韦尔作为该州的首席专家,对这些公司及其算法的运作方式进行了 170 小时的研究。他发现了一种非常强大和高效的技术,可以根据实时情况和数百万次行程的数据无缝匹配工人的工作、设置时间表并确定价格和报酬。

Uber 和 Lyft 否认了韦尔关于乘客票价和司机收入的说法。一位发言人说,在 Uber,计算基于路线:出发地、目的地、日期和时间以及供需。乘客和司机的特征或行为不被考虑在内。

根据新的 32.50 美元/小时的工资率(包括司机的汽油和汽车保养等费用),车费和工资仍将以相同的方式计算,但每两周将分析一次收入,并根据需要进行调整以达到新的最低标准。

Uber 表示,某些司机可以获得促销活动,例如在特定时间和地区开始的行程的额外报酬,过去的表现可以决定其资格。

当然,这些算法创造了社会效益。 Uber 和 Lyft 为原本可能没有交通工具的乘客提供了交通服务。研究发现,这类平台增加了低技能工人的就业机会,从而减少了犯罪和酒后驾车死亡人数。

但劳工专家表示,这种算法让公司能够以尽可能低的成本从工人和乘客身上榨取更多利润,从而增加利润。这些平台运营的效率可能会鼓励公司雇用更多独立承包商,而这些承包商不受最低工资法、失业保险、工人赔偿或其他安全网的保护。研究表明,避免这些责任可以将劳动力成本降低约 30%。

韦尔表示,承包商的使用增加也可能对普通员工的工资造成下行压力。而且,由于司机的工资可以个性化——被称为“算法工资歧视”——他们也更难理解自己的工资是如何支付的,以及他们是否需要反击他们认为的不公平。

61 岁的莱昂内尔·德安德拉德 (Leonel De Andrade) 来自布罗克顿,全职为 Uber 和 Lyft 开车,有时每天工作 12 小时,每周工作 7 天,才能维持生计。他很清楚,该平台以他不完全理解的方式控制着他工作的方方面面,而不仅仅是行程和工资。他说,如果他发生事故或遇到其他问题,很难找到人交谈。“算法就是一切。”

伦敦经济学教授、牛津大学人工智能伦理研究所高级研究员丹尼尔·萨斯坎德 (Daniel Susskind) 表示,在这种情况下,低薪工人损失最大,因为他们更有可能需要工资,也更愿意接受比其他人更低的工资。

“这些系统被用来对劳动力市场中那些本就不安全的领域进行这种工资歧视,这特别不公平,”他说。

在任何可以进行合同工作的行业——从医疗保健到零售再到法律——算法都可以渗透进来。例如,人工智能可以根据类似情况的护士轮班的意愿来确定合同护士可能接受的最低工资。

在餐饮服务中,人工智能平台可以只在晚餐高峰期招募合同工,从而节省安排更多正式员工轮班的成本。招聘算法可能会从列出低工资开始,然后逐渐将其提高 1 美元/小时,直到达到工人可以接受的神奇数字。

“这是工资悬而未决的问题,”北卡罗来纳大学研究零工经济的社会学教授亚历山大·拉维内尔 (Alexandrea Ravenelle) 说。 “你能把工资降到多低才能招到工人?”

当然,技术在很多方面改善了就业——允许远程工作、增加灵活性和自动化日常任务——但 萨斯坎德和其他人警告说,技术也可能使就业情况变得更糟。

部分问题在于劳动法没有跟上 21 世纪的步伐,而技术允许公司监控工作的几乎每个方面、分析大量数据,并使用这些信息来分配工作和确定薪酬。劳工专家表示,这让无法获得这些信息的工人处于极大的劣势。

经济学家将这种不平衡称为“信息不对称”。

“信息不对称为拥有信息的一方创造了权力,”波士顿大学信息系统教授马歇尔·范·阿尔斯汀(Marshall Van Alstyne )说,他最近共同主持了一场关于平台战略的会议。“而算法对 Uber 和 Lyft 所做的正是如此。”

范·阿尔斯汀表示,帮助重新平衡的一种可能方法是与司机共享数据,让他们能够更好地决定何时何地工作。

基于应用程序的工作提供的这种灵活性对工人来说是一个巨大的卖点。但宾夕法尼亚大学管理学教授林赛·卡梅伦(Lindsey Cameron )表示,依靠平台谋生的 Uber 和 Lyft 司机可能会受到算法的推动,在高需求的时间和地点工作以赚取更多钱。

卡梅伦说,许多司机可能觉得他们别无选择,只能接受这些工作,即使这些工作不方便。

“这种自主性让人们感觉很真实,”卡梅伦说,他曾兼职做优步司机三年。但这更像是“你妈妈说你可以吃西兰花或胡萝卜,但无论哪种方式,你吃的都是蔬菜。”

《环球报》的迪蒂·科利对本报告做出了贡献。

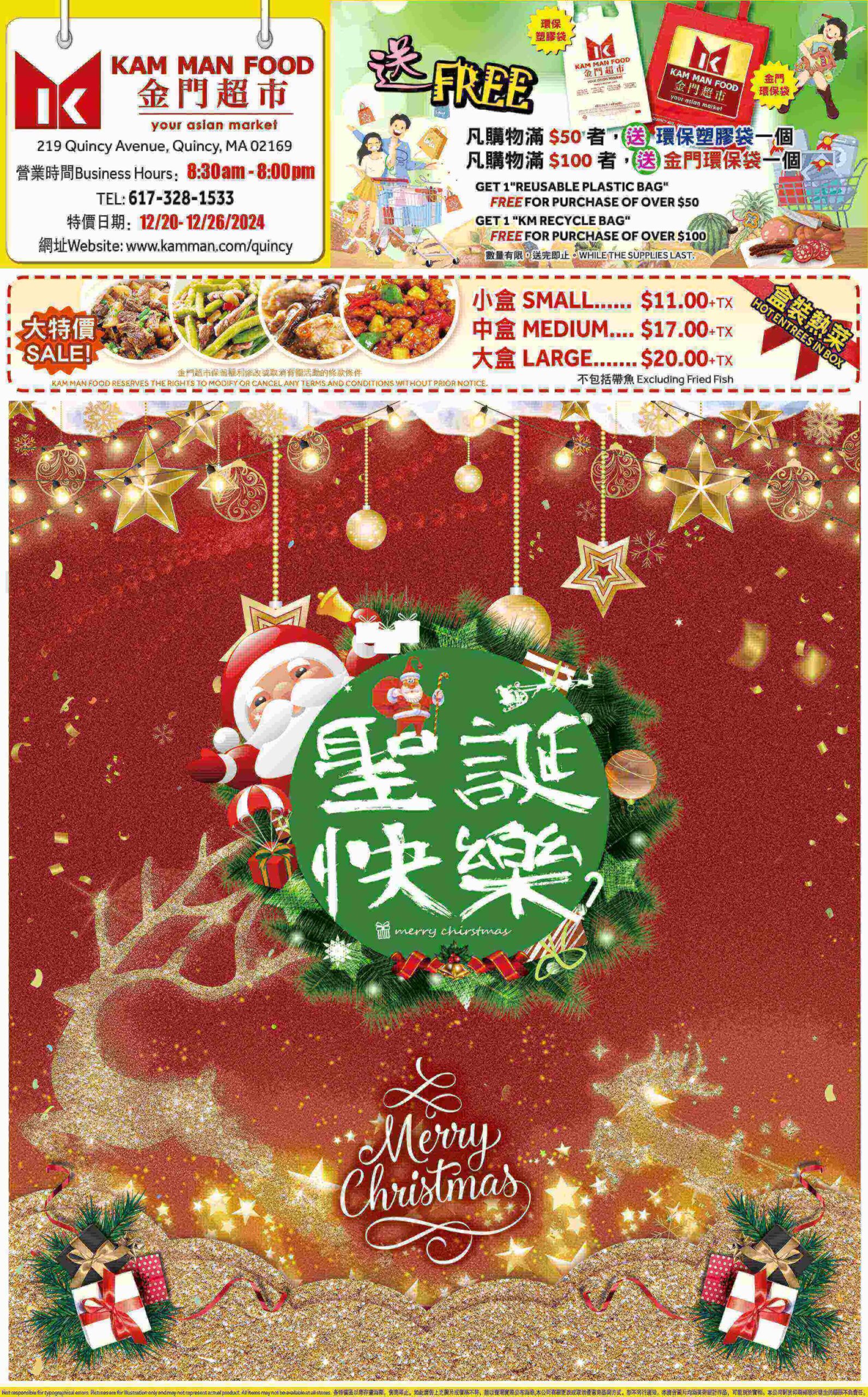

题图:上个月,旅客在波士顿洛根机场的叫车区查看手机。最近对 Uber 和 Lyft 司机就业权利的审判揭示了人工智能如何指导他们的商业模式。Jessica Rinaldi/Globe Staff

附原英文报道:

Who’s really at the wheel for Uber and Lyft? In many ways, it’s AI.

Trial testimony reveals the power of the companies’ algorithms — and raises questions about its impact on labor

By Katie Johnston Globe Staff,Updated August 3, 2024

David Weil, a Brandeis University professor and labor market expert, knew that Uber and Lyft had long used algorithms to match the supply of drivers to demand from riders, and set prices accordingly.

But as he sifted through depositions, documents, and data made available in a recent Massachusetts lawsuit against the ride-hailing companies, he discovered the artificial intelligence behind the algorithms was far more sophisticated than he imagined. The algorithms, learning from massive amounts of data gleaned from millions of trips, could predict how much riders in certain situations might be willing to pay, and how much compensation drivers might accept.

After a Celtics game, for example, someone heading to Weston might be charged a higher rate than another person going to Framingham, based on the insight that Weston passengers might be wealthier and willing to pay more to get home quickly, Weil found. High demand after a game can also prompt the algorithms to increase wages to get more drivers on the road, but it’s not a level playing field.

Those drivers considered high value may earn additional incentives to drive more, while others may get fewer opportunities. But neither the customers nor the drivers fully realize how or why they’re treated differently.

Weil’s findings offer a glimpse into the power of AI and its potential to reshape the relations between companies, workers, and consumers. AI’s ability to almost instantly sift through mountains of data collected from apps, online activities, and point-of-sale systems could give companies great advantages. It would allow them to customize prices and pay according to individual circumstances and would mean that each decision consumers and workers make could eventually factor into how much they pay or get paid.

“One of the things that is troubling about the greater and greater use of very, very nuanced data harnessed to AI and machine learning is that you can figure out ways, essentially, to coax out people with exactly the amount you need to pay them to get them to work,” said Weil, the former head of the Department of Labor’s wage and hour division. “And not a penny more.”

The insights into how Uber and Lyft operate grew from materials turned over to state during the discovery phase of a lawsuit against the companies for misclassifying drivers as independent contractors rather than employees. The case was settled the day before closing arguments, awarding drivers new benefits, wages starting at $32.50 an hour, and back pay, but didn’t resolve drivers’ employment status (employee or contractor?) or address the transparency of the companies’ algorithms.

Weil, as the state’s lead expert, conducted 170 hours of research into how the companies and their algorithms operate. What he found was astonishingly powerful and efficient technology that seamlessly matches workers to work, sets schedules, and determines prices and pay according to real-time circumstances and data from millions of trips.

Uber and Lyft rejected Weil’s assertions about rider fares and driver earnings. At Uber, the calculations are based on routes: origin, destination, day and time, and supply and demand, a spokeswoman said. The characteristics or behaviors of riders and drivers aren’t factored in.

Fares and wages will still be calculated the same way under the new $32.50 hourly pay rate (which accounts for drivers’ expenses such as gas and car maintenance), but earnings will be analyzed every two weeks and adjusted if needed to meet the new minimum.

Promotions, such as extra pay for trips that begin in certain times and areas, are offered to certain drivers, and past performance can determine eligibility, according to Uber.

Certainly, these algorithms have created social benefits. Uber and Lyft are providing transportation to riders who might not otherwise have it. Research has found that these types of platforms increase employment for low-skilled workers, and result in fewer crimes and fewer drunk-driving fatalities.

But such algorithms give companies even greater ability to squeeze more out of workers and passengers, at the lowest possible cost — and increase profits, labor experts say. The efficiency with which these platforms operate could encourage companies to hire more independent contractors, who aren’t protected by minimum wage laws, unemployment insurance, workers’ compensation, or other safety nets. Research shows that avoiding these responsibilities can cut labor costs by roughly 30 percent.

The increased use of contractors could also put downward pressure on the wages of regular employees, Weil said. And because drivers’ pay can be individualized — referred to as “algorithmic wage discrimination” — it’s also more difficult for them to understand how they are paid and whether they need to push back against what they feel are inequities.

Leonel De Andrade, 61, of Brockton, drives full time for Uber and Lyft, sometimes working 12 hours a day, seven days a week to get by. He’s well aware that the platform controls every aspect of his job in ways that he doesn’t fully understand, and it’s not just about trips and wages. If he gets into an accident or has other issues, it can be difficult to find a human to talk to, he said. “The algorithm is everything.”

Low-wage workers in these situations have the most to lose, said Daniel Susskind, a London economics professor and senior research associate at the Institute for Ethics in AI at Oxford University, because they are more likely in need and willing to accept less than others.

“There’s something particularly unjust about these systems being used to do this sort of wage discrimination in those already insecure parts of the labor market,” he said.

In any industry where contract work is possible — from health care to retail to law — algorithms can infiltrate. AI could determine the lowest wage contract nurses might accept, for example, based on the willingness of similarly situated nurses to take shifts.

In food service, AI platforms could bring in contract workers just for the dinner rush, saving the cost of scheduling more regular employees for a full shift. The hiring algorithm might start by listing a low wage and gradually raise it by $1 an hour until hitting the magic number workers will accept.

“It’s wage limbo,” Alexandrea Ravenelle, a sociology professor at the University of North Carolina who studies the gig economy. “How low can you go and still get workers?”

Technology has improved jobs in many ways, of course — allowing remote work, increasing flexibility, and automating mundane tasks — but Susskind and others warn there’s also a danger it could make them worse.

Part of the problem is labor laws haven’t caught up to the 21st century and the technology that allows companies to monitor almost every aspect of work, analyze vast troves of data, and use that information to assign work and determine pay. It puts workers, who don’t have access to this information, at great disadvantage, labor experts said.

Economists call this imbalance “information asymmetry.”

“Information asymmetry creates power for the party that has the information,” said Marshall Van Alstyne, an information systems professor at Boston University who recently cochaired a conference on platform strategy. “And the algorithms are doing exactly that for Uber and Lyft.”

One possible way to help reset the balance would be to share data with drivers, Van Alstyne said, allowing them to make better decisions about when and where to work.

This kind of flexibility provided by app-based jobs is a huge selling point for workers. But Uber and Lyft drivers who rely on the platforms to make a living are likely compelled by algorithmic nudges offering more money to work at high-demand times and locations, said Lindsey Cameron, a University of Pennsylvania management professor who testified for the state.

Many drivers may feel they have no choice but to take the jobs, even if they’re not convenient, she said.

“This autonomy feels real to people,” said Cameron, who worked part time as an Uber driver for three years. But it’s more like “your mother saying you can have broccoli or carrots, but either way you’re eating vegetables.”

Diti Kohli of the Globe staff contributed to this report.