洪水、细菌、敌意:瓦尔登湖的宁静就此终结

【中美创新时报2024 年 7 月 28 日编译讯】(记者温友平编译)游泳者与渔民。人群与大自然。夏天,梭罗心爱的隐居地瓦尔登湖可能会出现紧张局势。《波士顿环球报》环球杂志记者威廉·J·科尔(William J. Kole)对此作了下述深度报道。

“我去树林里是因为我希望慎重地生活,只面对生活的基本事实,看看我是否能学到它所要教的东西,而不是在我死后发现我从未活过。”

——亨利·戴维·梭罗,《瓦尔登湖》

苏珊·布劳来到康科德的树林,因为她希望慎重地游泳。

布劳用宽阔而有力的划水动作穿过瓦尔登湖,远远超出了孩子们嬉水和警惕的父母涉水的绳索区。这是她快乐的地方——一个水生世外桃源,在这里她可以找到节奏,清除脑海中的杂念。

尤其是这幅特别不雅观的画面:由于许多挤满瓦尔登细长沙嘴的海滩游客最终都会在浅水区小便,研究人员表示,人类尿液的浓度会增加磷和氮的含量,并为大量黏糊糊的绿藻提供养分。今年,该州多次因细菌数量高而关闭海滩。

“我没有想过这个,”51 岁的贝德福德人布拉夫说,他穿着潜水服和帽子——也许是偶然的,考虑到水里的东西——最近一个 90 华氏度的工作日。

瓦尔登的水问题激发了模因和头条新闻作者的灵感,2018 年的一份报告强调了这个问题,警告几代游泳者在水中做事对生态造成毁灭性的影响。考虑到梭罗的这句话:“纯净的瓦尔登湖水与恒河的圣水混合在一起”,这真是一个充满讽刺的启示。

“亨利,它混合的还不止这些,”在线出版物《Electric Lit》的编辑艾琳·巴特内特当时打趣道。

这是一个越来越明显的现象中不为人知的一面:涌向瓦尔登湖州立保护区的游客,其中许多人受到梭罗 1854 年的经典著作《瓦尔登湖》的启发,他们可能既体验到喧嚣,又体验到幸福——至少在夏天是这样。

如今,每年有近 60 万人来访,挤满了自 1962 年以来一直是国家历史地标的这个地方。人群留下了不可磨灭的印记,但瓦尔登湖也面临着难以控制的气候。

春季和初夏连续第二年暴雨肆虐,淹没了海滩,直至池塘的石挡土墙。这促使管理瓦尔登湖的州自然保护和娱乐部采取不同寻常的措施,敦促寻找避暑地点的人们考虑其他公园。官员们还限制了可用的停车位数量,以减缓海滩游客的涌入。

今年夏天,游客们找到了新的地方来铺毯子和椅子,包括池塘旁边的倾斜树林和周围的人行道。岸边的树木之间摆满了吊床。“我们已经有人试图在海岸线上寻找自己的游泳地点,他们践踏植物和栖息地,破坏池塘的生态,”DCR 游客服务主管 Kyle Griffiths 上个月在 Instagram 上发帖称。

“人们实际上正在砍断保护池塘边缘的围栏,如果这种情况持续下去,我说我们要给围栏通电!”另一位 DCR 官员 Ryan Hutton 补充道。最后一点是开玩笑,但发生在瓦尔登湖上的事情可不是开玩笑的事。

“我从未找到像孤独一样友好的同伴。”

——梭罗,《瓦尔登湖》

这位超验主义作家于 1845 年 7 月 4 日搬到了瓦尔登湖当时宁静的海岸。他建造了一个简陋的单间小屋,在那里生活和写作了两年零两个月零两天,他从未想过会有人蜂拥而至。

在阵亡将士纪念日和劳动节之间,瓦尔登湖的海滩通常像科尼岛一样挤满了游客——而且人群并不局限于海岸。

在池塘中央,悬挂在深受垂钓者和公开水域游泳者喜爱的漆黑深水中,桨板运动员、划船者和游泳者时不时发生冲突。尽管池塘看起来很平静,但也可能很危险:本月早些时候,一名 62 岁的奥尔斯顿男子的尸体被从池塘中打捞出来,他似乎是溺水身亡。

一名渔民说,他甚至打电话给州警察,因为当他在岸边钓鱼时,一名游泳者冲到他面前威胁他。尽管瓦尔登湖的规定禁止游泳者靠近船或垂钓者 50 英尺以内,并警告缠绕鱼线违反州法律,但这种情况还是发生了。

“你会听到一些关于一些脾气暴躁的人的坏故事:游泳者因为渔民离他们太近而生气,[渔民] 只是在他们上方徘徊,诸如此类,”Concord Outfitters 的店员 Vinny Giurleo 说,这家高档商店距离瓦尔登几英里,专门为飞钓者提供服务。

“肯定会遇到一些不太友善的人,无论是渔民挡住了游泳者的路,还是反之亦然,”Giurleo 说。“我们有一些非常善解人意的渔民,他们总是会避开游泳者的路。问题似乎在于人们不认为瓦尔登是一个钓鱼池。他们认为它是一个游泳池。”

Brie Rohan 是第三代康科德人,经营着她家族的皮划艇和独木舟租赁业务 South Bridge Boathouse,她说她的一些客户现在更喜欢在康科德河上划船,而不是与瓦尔登的游泳者打交道。

“他们非常敌视我,”她说,“对于一个富裕的小镇来说,我总是说我们付了钱,因为一切都太完美了,但这里却充满敌意。如果你周末去那里,你会像沙丁鱼一样挤在那里。那里的平静被剥夺了,因为你坐在那里担心撞到游泳者。”

然而,与游泳者的冲突,以及偶尔缠结的钓鱼线,并不是瓦尔登湖唯一的紧张源头。

瓦尔登湖和附近的康科德民兵国家历史公园被列入国家历史保护信托基金最新公布的美国 11 个最濒危历史遗址名单。这份年度排名重点关注了面临破坏或不可挽回的损害风险的美国历史重要遗址。

今年春天,该基金会表示,汉斯科姆菲尔德机场的大规模扩建计划将威胁沃尔登,扩建计划“可能会大幅增加私人飞机的运输量,导致噪音和车辆交通增加,并对环境和气候产生负面影响。”

“游客从这些对美国文学复兴和环保运动意义重大的地方获得灵感,”该基金会在一份声明中表示,并警告说“这个极其重要的历史地区……不适合进行这种规模和潜在影响的开发。”

然而,这些游客本身也在破坏文学和环境的象征意义,而正是这种象征意义吸引了这么多人来到这里。

“我家里有三把椅子;一把代表独处,两把代表友谊,三把代表社会。”

——梭罗,《瓦尔登湖》

呼唤梭罗:社会需要更多的椅子。

公平地说,瓦尔登湖——大约 10,000 年前由退缩的冰川雕凿而成——甚至在梭罗住在他的朋友兼导师拉尔夫·沃尔多·爱默生拥有的土地上时,也算不上是一个与世隔绝的避难所。

梭罗本人写道:“火车车厢的嘎嘎声,一会儿消失,一会儿又像鹧鸪的鸣叫一样重新响起,将旅行者从波士顿带到乡村。”铁路仍然在那里,藏在树后,载着乘坐马萨诸塞州湾交通局菲奇堡线往返于瓦楚塞特和波士顿北站之间的通勤者。

从某种程度上来说,2024 年的瓦尔登湖比《瓦尔登湖》出版时更加与世隔绝。游客中心的一张手绘地图证实了这一点:这座占地 462 英亩的公园建于 20 世纪 70 年代,如今森林覆盖率远高于 170 年前占主导地位的农场和小屋,其中一些由前奴隶居住。

即便如此,在任何一个夏日,该地区都挤满了游客和当地人。“大多数人过着平静的绝望生活”是梭罗在《瓦尔登湖》中最令人难忘的诗句之一,而最近,“大众”成了关键词。

尽管瓦尔登湖以清澈见底而闻名,湖中养有鳟鱼和鲈鱼,但那些想吃自己捕获的鱼的人应该注意有关鱼类消费的建议。马萨诸塞州公共卫生部警告称,瓦尔登湖和该州其他数十个池塘、湖泊和水库的汞和 PFAS(也称为“永久化学物质”)含量过高。(除其他警告外,该部门的网站建议儿童和孕妇或哺乳期妇女不要食用瓦尔登湖的大嘴鲈鱼或小嘴鲈鱼。)

瓦尔登湖在夏天也经常有徒步旅行者和观鸟者,在冬天则有雪鞋徒步者和越野滑雪者。许多人从环绕长方形池塘的 1.7 英里阴凉泥路中走出来,折断树枝,践踏野花。

水土流失已成为一个大问题,现在铁丝网可以防止徒步旅行者偏离池塘周围的主路。 “现在的湖泊生态系统与梭罗所描述的完全不同,”纽约阿迪朗达克山脉保罗史密斯学院的自然科学教授 J. Curt Stager 说道,他广泛研究了人类活动对瓦尔登湖的影响。

他说,瓦尔登湖面临着巨大的威胁:为湖泊提供氧气的杂草床最终可能会被藻类繁殖所窒息,而藻类繁殖是由污染物引起的,这些污染物在某些地方使水变得浑浊。

Stager 表示,瓦尔登湖的深度——102 英尺——有助于阻止目前锁在湖底长达两个世纪的富含营养的沉积物。但随着气候变暖,水位最终会下降(尽管今年发生了洪水),而当这些营养物质激增时,前景黯淡。

“气候变化将使那里发生的一切变得复杂,”Stager 说道。“池塘处于危险之中。DCR 的优秀员工被拉向不同的方向。他们试图保护池塘,同时也保护那里的公共娱乐机会。”

对于一些游客来说,瓦尔登湖只是一个可爱的郊区游泳胜地。但是,对文学史感兴趣的人却喋喋不休地乘坐大巴,像钟表一样被赶进瓦尔登湖的太阳能游客中心,那里有关于这位被认为是现代环保运动创始人的曾经的教师的互动展览。然后,他们被带去参观他小屋的复制品,从木门可以看到经常挤满人的停车场,让人难以忘怀。

事实上,最近 Tripadvisor 上的评论并不令人满意。

“一个喧闹嘈杂、令人失望的地方,”一位罗德岛人总结道。

“这里商业化过度,人太多了。去个更安静的地方吧,”一个家庭在 8 月参观后发帖说。

“与 4,000 名嬉戏游泳的人一起享受孤独的乐趣,”去年 7 月另一位游客说。“梭罗在坟墓里翻滚着……” ”

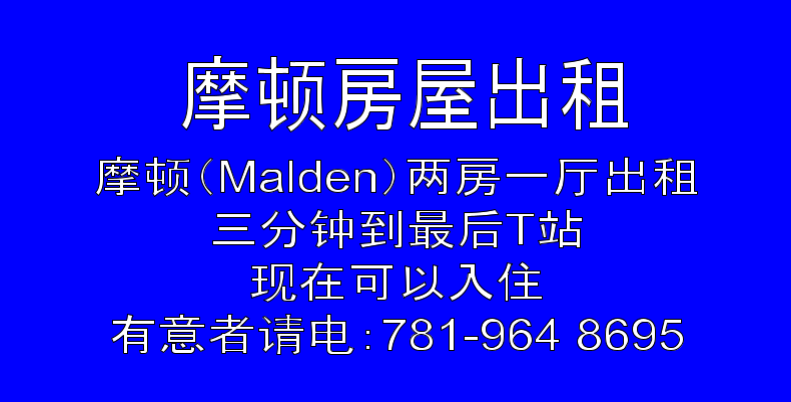

一张照片是池塘旁边的沙滩,几十个人坐在毯子和椅子上。水中还有不少人。

瓦尔登湖的停车场通常在中午前就已满员,促使公园官员在社交媒体上发布警告,称游客将被拒之门外。有些人不顾一切,把车停在小路上或附近的高中,然后走进去,但他们几乎肯定会在挡风玻璃上发现罚单——如果他们的车没有被拖走的话。

停车拥堵问题在 5 月份康科德的警方记录中占据了显著位置:“瓦尔登湖停车场附近接到 911 电话,称她旁边的一辆车停得太近,她无法打开车门上车。”

然而,这些都没有阻止瓦尔登湖的常客,比如 63 岁的康科德居民黛安·本诺斯,她每周至少和朋友一起来这里野餐一次。

“我更喜欢大海,但这太方便了,”她说。 “你来到这里,看到这么多人,但如果你四处走走,你会发现一些美丽的地方,只有你、瓦尔登湖和大自然。”

“如果存在价值和友善的核心,我们就不应该用我们的卑鄙来欺骗、侮辱和驱逐彼此。”

——梭罗,《瓦尔登湖》

船屋经理布里·罗汉看着瓦尔登湖,看到了社会弊病的反映。

“几乎没有同情心;没有共存的意愿,”她说。“我们在政治上是如此分裂,这渗透到很多事情中。每个人都如此紧张。我们都低下头,做自己的事情。”

尽管瓦尔登湖人很多,但它并不缺少崇拜者。公园的留言簿上有一位来自中国杭州的游客留下的题词,他潦草地写着:“梭罗在今天的中国很受欢迎。”

然而,每三十多个热情洋溢的条目中,总有一个条目能捕捉到一些朝圣者无法摆脱的厌倦感。

“让梭罗远离 IPA 和大学生”,一位来自萨默维尔的女士写道。

DCR 没有回复通过电子邮件和电话留言发送的有关过度拥挤和垂钓者与游泳者之间紧张关系的投诉问题。但一位拒绝透露姓名的护林员表示,他无权代表公园发言,他说官员们对抱怨泰然处之。“我的意思是,我们是一个距离波士顿 20 英里的小公园。而且现在不是 1845 年,”他说。

“在国家公园,大多数人不会离开公园道路,”他补充道。“在这里,大多数人不会离开池塘小径。如果你走其他任何道路,你就能找到你想要的所有孤独。这就像在高速公路上开车,期待看到大自然。离开高速公路。”

对于 54 岁的亚历克斯·布拉夫来说,这意味着一头扎进池塘,和妻子苏珊一起畅游一英里。

讽刺的是,这样做只是一种短暂的反抗行为,让人想起梭罗离开瓦尔登湖后写的一篇文章《公民不服从》。2021 年,在全州发生一系列溺水事件(包括在池塘发生的溺水事件)后,官员禁止在公开水域游泳,但在公众强烈抗议后迅速恢复了这一规定。“有些人发现,在梭罗的绿洲上长距离游泳是我们与自然界最伟大的联系,”一份有 11,000 多人签名的请愿书写道。

当被问及瓦尔登湖的人群和偶尔发生的冲突时,布拉夫说,大多数人都表现得很好。“不可避免地会有‘哎呀’之类的事情,”他说。“但我认为人们只是,‘哦,嘿,随便吧。’我没有看到水中有人打架。”

题图:今年夏初,人们在瓦尔登湖游泳时玩排球。ERIN CLARK/GLOBE STAFF

附原英文报道:

Flooding, bacteria, hostility: So much for Walden Pond’s tranquility

Swimmers vs. fishermen. Crowds vs. Mother Nature. In summer, tensions can simmer at Thoreau’s beloved retreat.

By William J. Kole Globe Magazine Updated July 22, 2024

“I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.”

– Henry David Thoreau, Walden

SUSAN BROUGH has come to the woods in Concord because she wishes to swim deliberately.

With broad, powerful strokes, Brough traverses Walden Pond well outside the roped-off area where children splash and watchful parents wade. This is her happy place — an aquatic arcadia where she can find a rhythm and empty her mind of distracting thoughts.

Especially this particularly inelegant mental picture: Because many of the beachgoers who cram Walden’s slender spit of sand end up peeing in its shallows, researchers say its human urine concentration boosts phosphorus and nitrogen levels and feeds blooms of slimy green algae. On multiple occasions this year, the state has closed the beach because of high bacterial counts.

“I don’t think about that,” says Brough, a 51-year-old from Bedford, who is clad — perhaps serendipitously, given what’s in the water — in a wet suit and cap on a recent 90-degree weekday.

Walden’s water problem inspired both memes and headline writers when it was highlighted in a 2018 report warning of the devastating ecological impact of generations of swimmers doing their business in the water. It was a revelation thick with irony, considering this Thoreau quote: “The pure Walden water is mingled with the sacred water of the Ganges.”

“That’s not all it’s mingled with, Henry,” Erin Bartnett, an editor at the online publication Electric Lit, quipped at the time.

It’s the unseen side of an increasingly visible phenomenon: Visitors who flock to Walden Pond State Reservation, many inspired by Thoreau’s 1854 classic, Walden; or, Life in the Woods, are as likely to experience bedlam as bliss — at least in summer.

Today, nearly 600,000 people visit annually, overrunning a site that’s been a National Historic Landmark since 1962. Crowds are leaving an indelible mark, but Walden is also reckoning with an unruly climate.

Torrential rains that hit in spring and early summer for a second consecutive year submerged the beach right up to the pond’s stone retaining wall. That prompted the state Department of Conservation and Recreation, which manages Walden, to take the unusual step of urging people looking for somewhere to cool off to consider other parks. Officials are also limiting the number of available parking spots to slow the rush of beachgoers.

This summer, visitors have found new spots to spread their blankets and chairs, including on the sloped woods abutting the pond and the walking path around it. Hammocks stretch between trees near the shore. “We already have people trying to find their own swimming spots along the shoreline, and they’re trampling plants and habitat and damaging the ecology of the pond,” Kyle Griffiths, the DCR’s supervisor of visitor services, said in an Instagram post last month.

“People are actually cutting the fencing put up to protect the pond’s edge, and if that keeps up, I say we’re going to electrify the fence!” added Ryan Hutton, another DCR official. That last bit was a joke, but what’s happening to Walden is no laughing matter.

“I never found the companion that was so companionable as solitude.”

— Thoreau, Walden

THE TRANSCENDENTALIST author moved to Walden’s then-tranquil shores on July 4, 1845. He built a sparse one-room cabin, where he lived and wrote for two years, two months, and two days, and could never have imagined the crush of humanity that would follow him.

Between Memorial Day and Labor Day, Walden’s beach is typically teeming, Coney Island-style, with visitors — and the crowds aren’t confined to the shore.

Out in the middle of the pond, suspended over the inky depths that are popular with anglers and open-water swimmers alike, paddle boarders, boaters, and bathers clash with some regularity. Despite its placid appearance, the pond can be dangerous: Earlier this month, the body of a 62-year-old Allston man was pulled from the pond after he apparently drowned.

One fisherman says he has even called the State Police after a swimmer got in his face and threatened him while he was fishing from shore. That happened even though Walden’s regulations forbid swimmers from coming within 50 feet of a boat or an angler and warn that entangling fishing lines violates state law.

“You’ll hear some bad stories about some pretty grouchy people: Swimmers mad about fishermen getting too close, [fishermen] just kind of hovering over them, stuff like that,” says Vinny Giurleo, a clerk at Concord Outfitters, an upscale shop a few miles from Walden that caters to fly-fishers.

“There are definitely encounters involving people who are not the nicest out there, whether it’s a fisherman getting in a swimmer’s way or vice versa,” Giurleo says. “We have some really understanding fishermen who are always OK about getting out of the way of swimmers. The problem seems to be that people don’t think of Walden as a fishing pond. They think of it as a swimming hole.”

Brie Rohan, a third-generation Concordian who runs South Bridge Boathouse, her family’s kayak and canoe rental business, says some of her clients now prefer to paddle the Concord River rather than deal with Walden’s swimmers.

“They’re very hostile,” she says. “For a wealthy town where I always say we pay the birds, because everything’s so perfect, there’s a lot of hostility. If you go on a weekend, you’re cramped in there like sardines. The peace of it is taken away because you’re sitting there worried about running into the swimmers.”

Conflicts with swimmers, as well as the occasional tangled fishing line, aren’t the only source of tension at Walden, however.

Walden and nearby Minute Man National Historical Park in Concord made the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s latest list of America’s 11 most endangered historic sites. The annual ranking spotlights significant sites of US history that are at risk of destruction or irreparable damage.

Walden, the trust said this spring, is threatened by a major proposed expansion of Hanscom Field airport, which “could significantly increase private jet traffic, leading to increased noise, vehicular traffic, and negative environmental and climate impacts.”

“Visitors draw inspiration from these places significant to the American literary renaissance and environmental movements,” it said in a statement, warning that “this extraordinarily important historic area … is not the right place for a development of this scale and potential impact.”

Those visitors themselves, though, are playing a role in compromising the very literary and environmental symbolism that draws so many here in the first place.

“I had three chairs in my house; one for solitude, two for friendship, three for society.”

— Thoreau, Walden

PAGING THOREAU: Society needs more chairs.

To be fair, Walden Pond — carved 10,000 or so years ago by a retreating glacier — wasn’t exactly a reclusive refuge even when Thoreau lived there on land owned by his friend and mentor, Ralph Waldo Emerson.

Thoreau himself wrote of “the rattle of railroad cars, now dying away and then reviving like the beat of a partridge, conveying travelers from Boston to the country.” The railway is still there, tucked behind the trees, carrying commuters riding the MBTA’s Fitchburg Line between Wachusett and Boston’s North Station.

In some ways, it’s more secluded in 2024 than it was when Walden was published. A framed hand-drawn map in the visitor center bears that out: The 462-acre park established in the 1970s is significantly more heavily forested today than the quilt-like patchwork of farms and cottages, including some inhabited by formerly enslaved people, that dominated the landscape 170 years ago.

Even so, on any given summer day, the area is teeming with tourists and locals. “The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation” is one of Thoreau’s most memorable lines in Walden, and lately, “mass” is the operative word.

Although Walden Pond’s famously crystalline waters are stocked with trout and contain trophy bass, those looking to eat their catch should heed advisories about fish consumption. The Massachusetts Department of Public Health warns of elevated levels of mercury and PFAS, also known as “forever chemicals,” at Walden and dozens of other ponds, lakes, and reservoirs in the state. (Among other warnings, the department’s website advises that children and pregnant or nursing women should not eat largemouth or smallmouth bass from Walden.)

Walden Pond is also frequented in summer by walkers and bird watchers, and in winter by snowshoers and cross-country skiers. Many wander off the 1.7-mile shaded dirt path hugging the oblong pond, breaking branches and trampling wildflowers.

Erosion has become such a problem, wire fencing now keeps hikers from straying off the main path around the pond. “The lake ecosystem is now quite different from that described by Thoreau,” says J. Curt Stager, a professor of natural sciences at Paul Smith’s College in New York’s Adirondacks who’s extensively studied the impact of human activities on Walden.

The pond faces a big threat, he says: The weed beds that oxygenate it could eventually be suffocated by algae blooms fueled by contaminants that cloud the water in places.

Walden’s great depth — 102 feet — is helping it keep at bay the two centuries’ worth of nutrient-rich sediment now locked on its bottom, Stager says. But as the climate warms, water levels eventually drop (despite this year’s flooding), and when those nutrients spike, the outlook is bleak.

“Climate change is going to complicate everything that’s happening there,” Stager says. “The pond is at risk. The good folks at the DCR are being pulled in different directions. They’re trying to protect the pond while also protecting the public recreation opportunities there.”

For some visitors, Walden Pond is simply a lovely suburban spot for a dip. But then there are the chattering busloads of those interested in the literary history, herded like clockwork into Walden’s solar-powered visitor center, which features interactive exhibits about the onetime schoolteacher considered a founder of the modern environmental movement. They’re then shown the replica of his cabin, where the timber doorway frames a forgettable view of the often-packed parking lot.

Indeed, recent reviews on Tripadvisor have been less than flattering.

“A busy noisy disappointment,” a Rhode Islander concluded.

“It’s over-commercialized and overrun with way too many people. Go somewhere more peaceful,” a family posted after visiting in August.

“Delight in solitude with 4,000 frolicking swimmers,” said another last July. “Thoreau is rolling in his grave . . . ”

A photo of a sandy beach next to a pond with a few dozen people sitting on blankets and chairs. There are a number of people in the water.

Walden’s lot often reaches capacity by midday, prompting park officials to post warnings on social media that visitors will be turned away. Defiant, some park on side roads or at the nearby high school and walk in, but they’re practically guaranteed to find tickets on their windshields — if their vehicles haven’t been towed.

The parking gridlock figured prominently in Concord’s police blotter in May: “911 call in the vicinity of Walden Pond parking lot reporting a vehicle next to hers is parked so close that she isn’t able to open her door to get in.”

Yet none of that deters Walden regulars such as 63-year-old Diane Bennos of Concord, who visits at least once a week with a friend to picnic.

“I love the ocean better, but this is so convenient,” she says. “You come here and see all these people, but if you walk around, there are some lovely spots where it’s just you and Walden Pond and nature.”

“We should never cheat and insult and banish one another by our meanness if there were present the kernel of worth and friendliness.”

— Thoreau, Walden

BRIE ROHAN, the boathouse manager, looks at Walden and sees a reflection of society’s ills.

“There’s almost no empathy; no willingness to coexist with each other,” she says. “We’re so divided politically, and that’s bled into a lot of things. Everyone is just so on edge. We all kind of put our heads down and do our own thing.”

Despite its crowds, Walden isn’t short of admirers. Among the inscriptions in the park’s guest book is one left by a visitor from Hangzhou, China, who scrawled: “Thoreau is very popular in China today.”

For every three dozen or so effusive entries, though, there’s one that captures that jaded feeling some pilgrims can’t shake.

“Reclaim Thoreau from IPA and college boys,” scribbled a woman from Somerville.

The DCR did not respond to questions — sent via email and phone message — regarding complaints of overcrowding and tensions between anglers and swimmers. But a ranger who declined to give his name, saying he isn’t authorized to speak for the park, says officials take the grumbling in stride. “I mean, we’re a small park 20 miles from Boston. And this isn’t 1845,” he says.

“In the national parks, most people don’t leave the park road,” he adds. “Here, most people don’t leave the pond path. If you go off any other path, you can find all the solitude you want. It’s like driving on the highway and expecting to see nature. Get off the highway.”

For 54-year-old Alex Brough, that means plunging headlong into the pond and sharing a vigorous mile swim with his wife, Susan.

Ironically, doing so was briefly an act of defiance reminiscent of “Civil Disobedience,” an essay Thoreau penned after leaving Walden. In 2021, officials banned open-water swimming following a statewide series of drownings, including at the pond, only to swiftly reinstate it after a public outcry. “Some find that the long swims across Thoreau’s oasis are our greatest connection to the natural world,” read a petition signed by more than 11,000 people.

Most people behave, says Brough, when asked about Walden’s crowds and occasional clashes. “There’s the inevitable ‘oops’ kind of thing,” he says. “But I think people are just, ‘Oh, hey, whatever.’ I’ve not seen any fistfights in the water.”