波士顿的办公室改住宅项目目前只有少数人接受

【中美创新时报2024年7 月 9 日编译讯】(记者温友平编译)波士顿市长吴弭政府帮助将未充分利用的办公空间改建为住宅的计划正在取得进展,但进展缓慢,目前只有少数人接受。《波士顿环球报》记者Jon Chesto 对此作了下述报道。

大约一个月前,波士顿市长吴弭与记者举行虚拟会议,讨论该市最新的经济分析,她吹嘘了她为波士顿疫情肆虐的市中心实施的办公室改建住宅项目的成功。

三天后,在海港举行的商业房地产贸易集团 NAIOP Massachusetts 会议上出现了不同的观点:一位开发商将结果描述为乏力,而另一位开发商将找到可行的改建方案比作大海捞针。

那么是哪一个呢?繁荣还是萧条?真相可能介于两者之间。我们暂时无法知道答案。就在吴弭的试点计划提供税收减免以鼓励住宅改建即将于 6 月 30 日到期之前,她宣布该计划将持续到 2025 年底——在希利政府承诺提供的 1500 万美元州援助的帮助下。

吴弭一年前宣布该计划时,她称赞这是在后疫情时代重新思考市中心的一种方式,通过帮助空置办公楼的业主将其改建为住宅用途。她提出了一项巨大的房产税减免,平均每年 75%,将持续长达三十年。几个月来,接受者相对较少。随着 6 月 30 日截止日期的临近,出现了一连串的活动。目前的总数:10 份申请,将在市中心或附近建造近 490 个单元,占地超过 450,000 平方英尺。其中两个已经获得波士顿规划与发展局的批准。

这是一个不错的开始。但这仍不到中央商务区办公空间的 2%。目前,几乎所有大型房地产业主都避而远之。

阻碍是什么?阻碍很多。

并不是很多办公楼都适合居住;机械系统、楼板和窗户通常无法对齐,无法轻松划分为住宅单元。装修费用迅速增加。而且相对较高的利率使得开发商目前难以获得各种项目的融资。

与此同时,大多数办公楼仍有一些支付租金的租户;想要改建的房东需要买下这些租户或等待租约到期。新城市碳排放和经济适用房规定也增加了开发成本。(改建计划中五分之一的住房单元必须是经济适用房,这很快将成为城市标准。)如果改建项目在头五年内售出,波士顿将征收 2% 的转让费。

考虑到所有这些,BPDA 主任阿瑟·杰米森(Arthur Jemison )表示他对迄今为止的进展感到满意。申请数量超出了他最初的预期。杰米森很快补充道,如果真的被淹没,那可能意味着写字楼市场将出现灾难性的自由落体。幸好这种情况还没有发生——至少现在还没有。

杰米森预计,新的州政府资金将支持数百套公寓。他还希望州议会正在推进的住房债券法案能提供更多鼓励;众议院版本(但不是参议院版本)提议对写字楼改建提供 10% 的税收抵免。杰米森指出,他有一名工作人员约翰·威尔,他的全职工作是与房东和开发商合作,推动这些项目,并加快它们通过 BPDA 审查。

亚当·伯恩斯就是其中之一。他的公司即将在富兰克林街 281 号一栋六层建筑中开始建造 15 套公寓。6 月底,伯恩斯提交了第二份申请,计划在市中心对面的 Fort Point 海峡对面的 263 Summer St. 建造 77 套公寓。他的公司 Boston Pinnacle Properties 专注于多户住宅项目,与许多专门从事办公室的市中心业主不同。2023 年初,在吴宣布她的激励计划之前,伯恩斯开始四处寻找可能适合改建的房产。但他说,如果没有税收减免,281 Franklin 的改建工作就无法奏效。

与戴夫·格里尼的经历形成鲜明对比。格里尼领导着 Synergy,这是市中心最大的房东之一,拥有许多可能更适合住宅改建的较小、较旧的建筑。但他目前的大型办公住宅改建项目位于伍斯特,他计划在盖特威城市住房州补贴计划的帮助下,在一个即将被 Fallon Health 腾空的综合大楼内建造 200 多套公寓。

Greaney 告诉 NAIOP 的人群,如果没有更好的公共激励措施,很难在波士顿找到一个可行的项目。在随后的采访中,Greaney 表示,既然州政府承诺提供 1500 万美元,他仍然对为波士顿改建项目提供资金抱有希望。但这仍然不是一件确定的事情。

Greaney 并不是唯一一个仍在寻找的人。

Day Pitney 的房地产律师 Jared Ross 说,去年他与人合写了关于该计划的备忘录后,听到了几个感兴趣的客户的消息;但还没有人上门。建筑公司 Gensler 的 Jared Krieger 说,他经常接到有关这里可能改建的电话。Gensler 的分析显示,他的团队评估的波士顿市中心办公楼中约有三分之一可以成功。但材料、劳动力和债务的成本仍然令人沮丧。

更慷慨的公共激励措施促使芝加哥和纽约等大城市实施更大规模的项目。

但真正的问题不是波士顿的计划与其他城市相比如何,也不是与市政厅最初的低预期相比如何。

不,真正的问题是:我们是否有足够的住房来弥补空置?以实质性的方式改变金融区和周边街区?目前市中心有近三分之一的办公空间可用,五百套公寓无法解决问题。

杰米森知道这一点。他说,他不认为这个项目是解决波士顿市中心困境的灵丹妙药,而是吴政府正在考虑的几种策略之一,旨在使该市的中央商务区成为一个更具活力的社区。

改变一座百年老办公楼已经够难了。改变一个挤满办公楼的整个社区?市政府官员的工作已经很艰巨了。

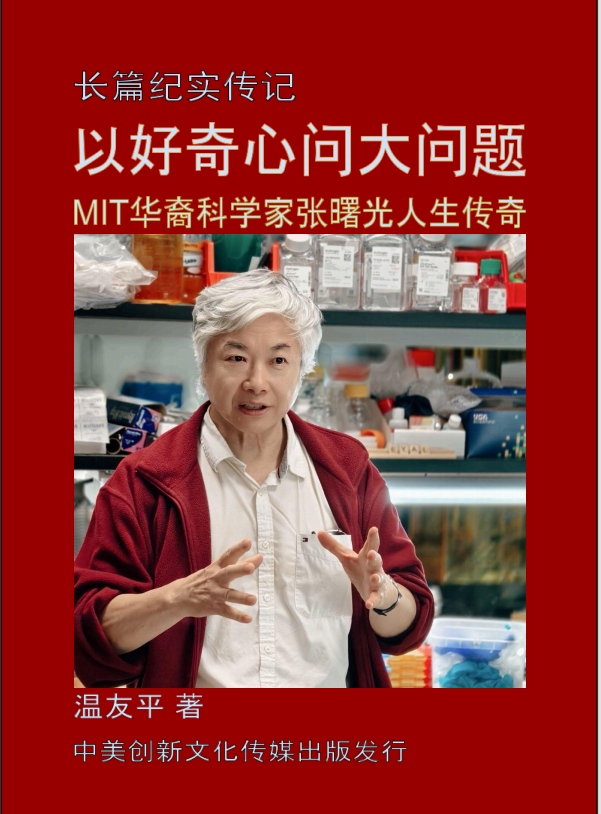

题图:波士顿 Pinnacle Properties 即将在波士顿市中心富兰克林街 281 号一栋六层建筑中开始修建 15 套公寓。DAVID L. RYAN/GLOBE STAFF

附原英文报道:

Boston’s office-to-residential conversion program has only a handful of takers so far. Here’s why.

The Wu administration’s program to help convert underused office space into housing is making progress, but slowly

By Jon Chesto Globe Staff,Updated July 9, 2024

Meeting virtually with reporters to discuss the city’s latest economic analysis about a month ago, Mayor Michelle Wu boasted about the success of her office-residential conversion program for Boston’s pandemic-stricken downtown.

Three days later, a different view emerged at a meeting held by commercial real estate trade group NAIOP Massachusetts in the Seaport: One developer described the results as anemic, while another likened locating a workable conversion to finding a needle in a haystack.

So which is it? Boom or bust? The truth will likely end up somewhere in between. We won’t know the answer for a while. Just before Wu’s pilot program offering tax breaks to encourage residential conversions was set to expire on June 30, she announced it will stay open through the end of 2025 — with the help of $15 million in state aid pledged by the Healey administration.

When Wu announced the program a year ago, she hailed it as one way to rethink downtown, post-COVID, by helping owners of hollowed-out office buildings convert them for residential use. She offered a huge property tax cut, an average of 75 percent annually, that would last up to three decades. For months, there were relatively few takers. Then came a flurry of activity as the June 30 deadline approached. The current tally: 10 applications, to build nearly 490 units, across more than 450,000 square feet, in or near downtown. Two have already won approvals from the Boston Planning & Development Agency.

That’s a nice start. But it’s still less than 2 percent of the office space in the central business district. And nearly all the big property owners are steering clear for now.

What’s the holdup? There are plenty.

Not many office buildings are ideal for housing; mechanical systems, floor plates, and windows often don’t line up for easy division into residential units. The renovation expenses add up quickly. And relatively high interest rates are making it tough for developers to secure financing for all sorts of projects right now.

Meanwhile, most office buildings still have some rent-paying tenants; landlords who want to convert need to buy them out or wait for their leases to expire. New city carbon-emissions and affordable housing mandates have also increased development costs. (One-fifth of the housing units in the conversion program need to be affordable, soon to be a city standard.) And Boston imposes a 2 percent transfer fee if conversions get sold in the first five years.

With all that in mind, BPDA director Arthur Jemison says he’s pleased with the progress so far. The number of applications exceeds his initial expectations. And if he had been flooded, Jemison quickly adds, that would have probably meant a catastrophic free fall for the office market. Good thing that hasn’t happened — at least not yet.

Jemison expects the new state funds will support several hundred more units. He also hopes a housing bond bill advancing at the State House provides more encouragement; the House version (but not the Senate’s) proposes a 10-percent tax credit for office-resi conversions. Jemison notes he’s got a staff person, John Weil, whose full-time job is to work with landlords and developers to spur these projects and speed them through BPDA review.

Among those is Adam Burns. His firm is about to start work on 15 apartments in a six-story building at 281 Franklin St. In late June, Burns submitted a second application, to build 77 apartments at 263 Summer St., just over the Fort Point Channel from downtown. His firm, Boston Pinnacle Properties, focuses on multifamily projects, unlike many downtown property owners that specialize in offices. Early in 2023, before Wu announced her incentive program, Burns started casting around for properties that could be ideal for conversions. But he says the numbers wouldn’t work to convert 281 Franklin without the tax break.

Contrast that to Dave Greaney’s experience. Greaney leads Synergy, one of downtown’s biggest landlords and owner of many smaller, older buildings that might be more suitable for residential conversion. But his big office-resi conversion project right now is in Worcester, where he plans to build more than 200 apartments in a complex that will soon be vacated by Fallon Health, with help from a state subsidy program for housing in Gateway Cities.

Greaney told the NAIOP crowd that it’s tough to find a project that works in Boston without better public incentives. In a subsequent interview, Greaney said he remains hopeful about financing a Boston conversion project now that the state committed $15 million. But it’s still not a sure thing.

Greaney isn’t the only one who is still hunting.

Jared Ross, a real estate lawyer at Day Pitney, said he heard from several interested clients after he co-wrote a memo about the program last year; none have bitten yet. And Jared Krieger at architectural firm Gensler says he regularly fields calls about possible conversions here. A Gensler analysis showed that around a third of office buildings in downtown Boston evaluated by his team could work. But the costs of materials, labor, and debt remain discouraging.

More generous public incentives have prompted larger projects in bigger cities such as Chicago and New York.

The real issue, though, isn’t how Boston’s program compares with other cities — or how it compares with City Hall’s low initial expectations.

No, the real issue is this: Are we getting enough housing to make up for the vacancies? To change the Financial District and surrounding blocks in a material way? With nearly one-third of office space in the downtown available right now, five hundred apartments won’t do the trick.

Jemison knows this. He says he doesn’t consider this program a panacea for what’s ailing downtown Boston, but instead one of several strategies that are being considered by the Wu administration to make the city’s central business district a more vibrant neighborhood.

Changing a century-old office building is hard enough. Changing an entire neighborhood, packed with them? City officials have got their work cut out for them.