【中美创新时报2024 年 6 月 16 日编译讯】(记者温友平编译)农业光伏,即利用土地进行农业和可再生能源的做法,在马萨诸塞州正在增加,从而形成了一些意想不到的合作伙伴关系。对此,《波士顿环球报》记者艾维·斯科特(Ivy Scott)作了下述详细报道。

菲奇堡农民杰西(Jesse)和艾尔斯佩思·罗伯逊-杜波依斯(Elspeth Robertson-Dubois )靠在他们的皮卡车后面,密切关注着他们的羊群。当太阳炙烤时,大多数羊群挤在一起,在最靠近他们的水桶的一排银色太阳能电池板下避暑。

但在山上更远的地方,在长长的太阳能电池板阵列中几乎看不见的地方,一只昏昏欲睡的小羊突然醒来,发现它的妈妈远在天边。

“那只小羊迷路了吗?”艾尔斯佩思·罗伯逊-杜波依斯听到它微弱的咩咩声后问道。然而不久之后,这只小羊就站稳了脚跟,在金属板的阴影下小跑着,直到它与羊群团聚。

这片土地曾经是一片废弃的苹果园,大约三年前被改造成一个太阳能农场,数百块太阳能电池板分布在 20 英亩的土地上。太阳能电池板的所有者是太阳能公司 Nexamp,该公司从果园所有者那里租赁了这片土地 25 年。在启动该农场后不久,该公司与罗伯逊-杜波依斯家族拥有的 Finicky Farms 合作。作为保持草丛稀少的交换,农民们从太阳能公司获得报酬,还可以将这片土地用作 215 只羊的免费放牧地,他们将这些羊加工后在当地作为羊肉出售。

对于绵羊来说,太阳能电池板可以保护它们免受高温、雨水和雪水的侵袭,有些绵羊在换毛季节甚至会把太阳能电池板底部当作抓柱。与此同时,和艾尔斯佩思·罗伯逊-杜波依斯表示,羊群在土地上稳定地消耗草料,可以防止草长得太高而阻挡阳光照射到太阳能电池板,从而保持太阳能电池板的生产效率。绵羊在吃草的同时,还可以改善土壤健康,这对植物多样性和在那里觅食的动物都有好处。

十年前,在用于安装太阳能电池板的土地上放牧绵羊对马萨诸塞州的农民和环保主义者来说都只是白日梦。但在 2018 年,该州通过其财政激励计划 SMART(即马萨诸塞州太阳能可再生能源目标)大力推动太阳能的发展,该计划要求公用事业公司支持小型太阳能项目的开发。太阳能电池板越来越多地安装在地面附近,而不是安装在建筑物屋顶上,这产生了和艾尔斯佩思·罗伯逊-杜波依斯所说的农业与可再生能源之间的“美好共生关系”,使一块土地的利用率翻了一番。

农业和太阳能之间的这种共享土地使用被称为农业光伏。据马萨诸塞州能源资源部称,马萨诸塞州至少有 45 个太阳能项目与农民共享土地。其中,目前有 7 个受益于 SMART 计划,使马萨诸塞州成为第一个为农业光伏提供财政激励的州。而且,据能源部门称,另外 14 个使用该计划的站点正在建设中。

虽然在太阳能电池板周围放牧是比较常见的例子之一,但在太阳能电池板的阴影下种植甜菜和胡萝卜等作物在过去十年中也越来越受欢迎。Finicky Farms 目前是马萨诸塞州为数不多的利用太阳能电池板下土地的放牧项目之一,但该行业正在整个新英格兰地区扩张。

“如果我们不放牧,我们就会雇佣割草机团队,”Nexamp Solar 的通讯经理基思·赫文诺(Keith Hevenor )说。“首先,他们在清洁能源场地燃烧化石燃料来割草,这有点反太阳能。”

而使用割草机,“这有点危险:你拿着割草机来到这里,开始踢起太阳能电池板周围的石头[或]撞到什么东西,”赫文诺补充道。“绵羊的影响要小得多,安全得多,而且对我们来说,这绝对是管理植被的更可持续的方式。”

这家太阳能公司还开始在纽约州北部的一个工厂试验养猪,赫文诺说,他们唯一不会使用的牲畜是山羊:“山羊喜欢爬山,它们什么都吃”——包括电线、电缆和栅栏,他说。

“我们实际上有一群山羊,”埃尔斯佩思·罗伯斯顿-杜波依斯说,“但我们不会在这种阵列中吃草,因为它们会很高兴地跳到电池板上!”她补充说,在倾斜的阵列或电池板组中,放牧山羊是可能的,这些电池板的太阳能电池板会随着太阳的移动而移动,并且离地面高得多。

美国最古老的太阳能农场于 20 世纪 80 年代在加利福尼亚州启动,这项技术花了几十年时间才发展成为如今的主要可再生能源产业。然而,尽管在 21 世纪,大片太阳能电池板变得越来越普遍,但在 2010 年代的大部分时间里,与牲畜共享土地的做法仍然很少见,美国太阳能放牧协会董事会成员、马萨诸塞州最早的太阳能放牧运营商之一 Solar Shepherd 的所有者 丹尼尔·芬尼根(Daniel Finnegan)表示,这种做法“在全国各地只是断断续续地发生”。

芬尼根于 2018 年作为创始成员加入该协会时,会员人数不到十几人。他说,今年,全国会员人数已增至约 800 人。

“真正的爆发,即现代太阳能放牧,始于 2018 年,”芬尼根解释说。“它实际上始于大伍斯特地区的马萨诸塞州派克公路沿线,一直延伸到五指湖。”

杰西·罗伯逊-杜波依斯 (Jesse Robertson-Dubois) 于 2021 年开始与女儿埃尔斯佩思 (Elspeth) 一起进行太阳能放牧,他亲眼目睹了马萨诸塞州中部太阳能的兴起,并很快渴望参与其中。

“我们从管理马萨诸塞州西部的一家农场转到管理马萨诸塞州东部的一家农场。有一年我开车来回,在那些太阳能电池板旁来回穿梭……我当时想,‘这里正在发生一些可能有用的事情!’”他说,回忆起他多次将卡车停在太阳能电池板旁,透过铁丝网凝视着电池板下冒出的数英亩细长的草丛。现在,他在马萨诸塞州的 10 个太阳能站点之间轮流放羊。

根据赫文诺的说法,在任何一天,仅菲奇堡站点就能产生 5 兆瓦的电力,足以为大约 800 户普通住宅供电。

环境科学家、马萨诸塞州保护委员会协会执行董事多萝西·麦克格林西(Dorothy McGlincy )表示,虽然环保人士强烈支持在住宅、停车场和其他建筑物上增加太阳能,但在某些情况下,例如在土壤质量差或农作物稀少的土地上,在开放的绿地上安装太阳能电池板是有意义的。

该协会“支持在不会影响优质农田、降低粮食生产能力、影响湿地资源或对开放空间产生负面影响的土地上开发清洁能源项目,”她说。

尽管由于规模的原因,马萨诸塞州的太阳能放牧场比其他州要小(Finnegan 说这里的太阳能农场往往接近十几英亩,而不是几百英亩),但他预计该行业在未来几年将继续蓬勃发展。

“太阳能公司选择这样做的原因是他们看到了土壤健康状况的改善,并看到这是利用这片土地的更好、更明智的方式,”他说。“马萨诸塞州,虽然我们是第一批这样做的州之一,但我们才刚刚开始触及表面。”

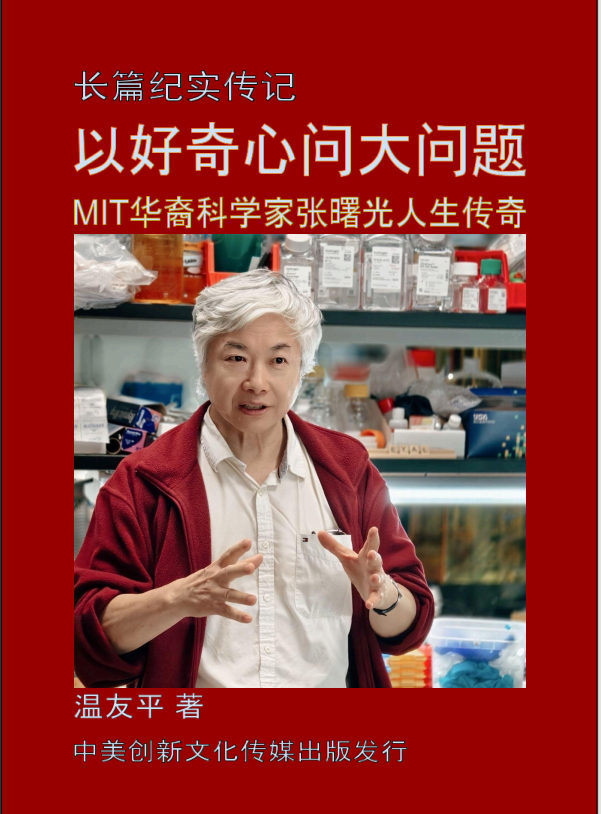

题图:超过 200 只绵羊在 Fitchburg Renewables 太阳能农场的 15,000 块太阳能电池板中吃草,这是一个 5 兆瓦的设施,为 700 名社区太阳能用户提供支持。JOHN TLUMACKI/GLOBE STAFF

附原英文报道:

What happens when sheep meet solar panels? A ‘beautiful symbiotic relationship.’

Agrivoltaics, or the practice of using land for both agriculture and renewable energy, is increasing in Massachusetts, making for some unexpected partnerships.

By Ivy Scott Globe Staff,Updated June 10, 2024

FITCHBURG — Leaning on the back of their pickup truck, farmers Jesse and Elspeth Robertson-Dubois kept a keen eye on their flock of sheep. As the sun beat down, the majority of the flock huddled together, sheltering from the heat under a row of silver solar panels closest to their buckets of water.

But further up the hill, almost out of sight amid the long array of panels, a sleepy lamb suddenly awoke to find its mother far away.

“Is the lamb lost over there?” Elspeth Robertson-Dubois asked, in response to its faint bleating. Before long, however, the lamb found its footing and trotted beneath the shade of the metallic panels until it was reunited with the flock.

Once an abandoned apple orchard, this land was converted roughly three years ago into a solar farm, with hundreds of panels spread across its 20 acres. The owner of the panels, solar company Nexamp, is leasing the land from the orchard owner for 25 years. Not long after launching the site, the company partnered with Finicky Farms, owned by the Robertson-Dubois family. In exchange for keeping the grasses low, the farmers are paid by the solar company and also get to use the land as a free grazing site for a flock of 215 sheep, which they process and sell locally as lamb.

For the sheep, the panels provide protection from heat, rain, and snow, with some sheep even using the base of the structure as a scratching post during shedding season. Meanwhile, Elspeth Robertson-Dubois said, the flock’s steady consumption of forage on the land prevents the grassy plants from growing high enough to block sunlight from reaching the panels, maintaining the productivity of the array. As they graze, the sheep also improve soil health, a benefit for plant biodiversity and animals that feed there.

A decade ago, grazing sheep on land intended for solar panels was a mere pipe dream for Massachusetts farmers and environmentalists alike. But in 2018, the state made a big push for solar with its financial incentive program, SMART, or Solar Massachusetts Renewable Target, which requires utility companies to support the development of smaller solar projects. The increase of solar panels closer to the ground, instead of on the roofs of buildings, has produced what Elspeth Robertson-Dubois called a “beautiful symbiotic relationship” between agriculture and renewable energy, doubling the usefulness of a single plot of land.

This shared land use between agriculture and solar power is known as agrivoltaics. There are at least 45 solar operations in Massachusetts sharing the land with farmers, according to the state’s Department of Energy Resources. Of those, seven currently benefit from the SMART program, making Massachusetts the first state to offer financial incentives for agrivoltaics. And, according to the energy department, an additional 14 sites using that program are on the way.

While grazing around solar panels is among the more common examples, growing crops such as beets and carrots in the shade of solar panels has also increased in popularity over the past decade. Finicky Farms is currently one of only a handful of grazing operations in Massachusetts that make use of the land under solar panels, but the industry is expanding throughout New England.

“If we’re not grazing, we’re hiring lawn mower teams to come in,” said Keith Hevenor, communications manager for Nexamp Solar. “Number one, they’re burning fossil fuels to mow the grass on a clean energy site, which is kind of antisolar.”

And with mowers, “it’s somewhat risky: you come in here with a lawnmower and start kicking up rocks around solar panels [or] bump into something,” Hevenor added. “The sheep are a lot lower impact, a lot safer, and definitely a more sustainable way to manage the vegetation for us.”

The solar company is also starting to experiment with pigs at one of its sites in upstate New York, and Hevenor said the only livestock they won’t work with is goats: “Goats love to climb, and they eat everything” — including wires, cords, and fences, he said.

“We actually have a goat herd,” Elspeth Roberston-Dubois said, “but we don’t graze in this type of array because they would have a joy trying to jump on the panels!” She added that grazing with goats is possible in tilted arrays, or groups of panels, which have solar panels that move with the sun, positioned much higher off the ground.

The country’s oldest solar farm was launched in California in the 1980s, and it would take several decades for the technology to blossom into the major renewable energy industry it is today. However, even as acres of solar panels became more commonplace in the 21st century, for much of the 2010s, the practice of sharing the land with livestock was rare, occurring only “in little fits and starts around the country,” according to Daniel Finnegan, a board member of the American Solar Grazing Association and owner of Solar Shepherd, one of the earliest Massachusetts-based solar grazing operations.

When Finnegan joined the association as a founding member in 2018, there were less than a dozen members. This year, he said, membership has grown to roughly 800 nationally.

“The real eruption, this modern take on solar grazing, started in 2018,” Finnegan explained. “It really began along the Mass. Pike in the Greater Worcester area all the way out to the Finger Lakes.”

Jesse Robertson-Dubois, who started solar grazing with his daughter Elspeth in 2021, witnessed the rise in solar in Central Massachusetts firsthand and quickly became eager to get involved.

“We switched from managing a farm in Western Mass. to managing a farm in Eastern Mass. I had a year where I was driving back and forth, going up and down the pike by all those solar arrays … and I was like, ‘Something’s happening here that could work!’” he said, recalling the many times he pulled his truck over to a solar array to peer through the wire fence at the acres of wispy grass cropping up beneath the panels. He now rotates his sheep among 10 solar sites across Massachusetts.

On any given day, according to Hevenor, the Fitchburg site alone produces 5 megawatts of electricity, enough to power roughly 800 average-sized residential homes.

Dorothy McGlincy, environmental scientist and executive director of the Massachusetts Association of Conservation Commissions, said that while conservationists most strongly support the increase of solar on homes, parking lots, and other buildings, there are situations, such as on land with poor soil quality or few crops, where putting solar panels in open green space make sense.

The association “supports development of clean energy projects on land that will not impact prime farmland, reduce food production capacity, impact wetland resources, or negatively impact open space,” she said.

Although, because of its size, Massachusetts solar grazing sites trend smaller than other states (Finnegan said solar farms here tend to be closer to a dozen acres, rather than a few hundred), he expects the industry to continue blooming in the coming years.

“The reason solar companies go for this is because they’re seeing the improvement in soil health and seeing that this is a better, smarter way to use this land,” he said. “Massachusetts, while we were one of the first, we’ve only just started to scratch the surface.”